Welcome to the first issue of The Mozhi Criterion, a magazine devoted to literary appreciation and criticism, primarily centred on Indian literature. The Mozhi Criterion will publish original or translated essays that privilege an aesthetic point of view. It will also feature interviews with writers, translators, and artists who, in one way or the other, are preoccupied with questions of taste. We will also publish excerpts from quoted literary works, serving as context for readers to appreciate the essays better.

Immersion

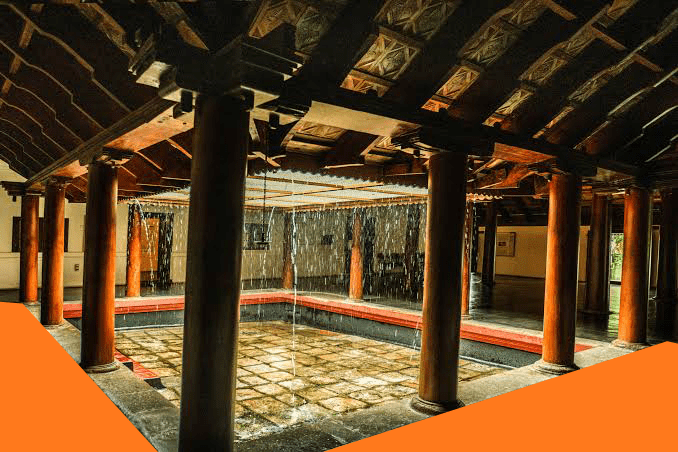

It was during last year’s monsoon that we first encountered the Krishnakireedam. We were in Sreekrishnapuram, a town in Palakkad district, Kerala. A misty rain kept up, occasionally parting to reveal a sea of green, lustrous like jade and malachite in the cloud-light. Punctuating the green were flame-like bursts of orange and red that drew our attention immediately. Was it Sita’s asoka? Or the blood-red sengkandhal, used to evoke bloody battlefields in classical Tamil poetry? No, this one was far bigger, though, the individual florets were smaller, more delicate, fragile, and filamentous. While these flowers shared a palette, the form of the one before our eyes was utterly different.

Tall and spiraling, like temple shikharas, the flowers rose like towers of flame that circle deities during the evening arathi. It was not a sacred flower, nurtured in temple grounds, or an ornamental blossom cultivated in gardens. It grew wild on the roadsides; and yet, we learned, was considered indispensable for the people’s festival of Onam. This flower was an entity all of its own, anchored to the specifics of its time and place, an entity like no other. Possessing ananyatvam, as tradition says. It was the flower’s ananyatvam that attracted us, that gave it its singular, local name — the Krishnakireedam, crown of Krishna — and allowed us to delight in its particularities.

To delight in particularities is one of the greatest pleasures nature, art, and aesthetics affords us. However, in recent times, there appears to be a poverty in our collective ability to exercise this faculty. Nowhere is this lack more apparent than in literature, particularly in anglophone India. As readers and literary translators, we have been following the manner in which Indian literary works are being discussed in the English media both in and outside the country. The common reader, we observe, is saddled with two predominant modes of speaking about these works: one, journalistic (often dry, factual summaries of its contents); and the other, reductionist (essays that are concerned with decocting the socio-political value of the work). Literary talk has become either an exercise in auditing or virtue signalling. The third mode of appreciating and critiquing art — the aesthetic — that is to say, immersing oneself in a text and reflecting on its particular beauty — its ananyatvam — by engaging deeply and sincerely with its world, is sorely missing. The Mozhi Criterion is our attempt to bring the aesthetic to the front and centre of literary discourse.

*

Welcome to the first issue of The Mozhi Criterion, a magazine devoted to literary appreciation and criticism, primarily centred on Indian literature. The Mozhi Criterion will publish original or translated essays that privilege an aesthetic point of view. It will also feature interviews with writers, translators, and artists who, in one way or the other, are preoccupied with questions of taste. We will also publish excerpts from quoted literary works, serving as context for readers to appreciate the essays better.

While The Mozhi Criterion will be primarily published in English, our content will also be available in other Indian languages to enable conversations between our like-minds from various languages. Even as contemporary culture votes in favour of ultra-short narrative forms to cater to shrinking attention spans, The Mozhi Criterion shall favour long-form writing that engages the reader with original thought and provocative ideas.

In naming the magazine, we tip our hats to T.S. Eliot, whose legacy we ambitiously invoke. Eliot asserted that the function of literary criticism is to “promote the understanding and enjoyment of literature,” stressing that “to understand comes to the same thing as to enjoy it for the right reasons.” With The Mozhi Criterion, we wish to take the idea of ‘understanding’ one step further.

*

Literature in the 20th century, for historical reasons, came to be occupied with questions of power and diversity, and began to represent marginalized voices. However, in a capitalist society identities are also markets. So, literature, too, has created markets out of diversity, including translated literature. When reading the stories of the ‘other’ becomes an exercise in box ticking and virtue signalling, as opposed to a deep engagement with the lives and perspectives of the ‘other’ — an appreciation of their ananyatvam — then our understanding can be flawed.

We believe that literature is one of the most honest ways to inhabit the ‘other.’ Without a full sensory ‘immersion’ in the other, true understanding is not possible. Literary ‘enjoyment,’ as Eliot puts it, is how one immerses oneself in the other. In enjoyment, we lose our sense of self and feel no difference between us and the other. This, we believe, nurtures empathy and true understanding.

The question of ‘immersion in the other’ brought us back to the literary traditions of India. For many Indians, the ‘other’ is not the West, but India itself: the many Indias within India. For the urban anglophone reader, these traditions, where their roots may lie, are yet distant and often considered a strange ‘other.’ While modern literary criticism may have emerged in the West, there are significant traditions of Indian writers from various languages who have engaged originally with the aesthetics of their literary practice. As far back as in the 1950s, we had writer-critics like Ka.Na. Subramanyam (Ka. Na. Su.) in Tamil who declared that literary criticism is literature itself; that it is a creative pursuit in as much as writing fiction is.

Ka. Na. Su. also asserted that it is not possible for a literary critic to be without attachment and to tread the middle path. On the contrary, he exhorts the literary critic “to develop attachments. Not one, or a hundred, or a thousand, but tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of attachments, to view literature simultaneously from numerous perspectives and enjoy them all.” And that is what we want to foreground through The Mozhi Criterion. Original, creative, homegrown voices that immerse themselves in the ‘other,’ that appreciate their ananyatvam, that can speak with vitality and enjoyment about literature and teach us to read deeper.

*

Our first issue is centred on one such voice: the Malayalam writer and critic K.C. Narayanan (K.C.N. in short). We discovered his essays through the work of Azhagiya Manavalan, K.C.N.’s Tamil translator.

Azhagiya Manavalan is another example of the value of ‘immersion’ we speak of above. A Tamilian by birth, with no roots or attachments to Kerala, he was taken by storm by the ideas of Malayalam writer and literary critic P.K. Balakrishnan. Subsequently, within the span of a year, he learnt Malayalam well enough to translate from the language into Tamil. He also immersed himself into the performing arts of Kerala, emerging as a connoisseur of Kathakali and Koodiyattam. It was during his process of discovery of Malayalam art and culture that Manavalan was introduced to K.C. Narayanan, and began translating his essays into Tamil.

K.C. Narayanan is one of Kerala’s foremost intellectuals. A writer, critic and journalist, his critical essays are, first and foremost, immersive. K.C. Narayanan believes in close reading of literary works; he believes the text contains everything. Consequently, his ideas about literary works and, more broadly, Kerala culture, are original, startling, even pathbreaking. Born in Kizhiyedathu Mana, a 150-year-old Namboodiri illam in Sreekrishnapuram, K.C. Narayanan’s mature life began with an intellectual and existential distancing from his traditional roots. In conversation, he recalled how it was the end of his father’s generation and the beginning of his when the padippura or the arched gateway of the old house was pulled down. He found himself by immersion into a literary life: reading by turns the existentialists, the symbolists, and the modernist poets, eventually emerging as an editor and critic. Through an active journalistic and creative life spanning over fifty years, through many existential crises, art was the one value he held on to. ‘There is no absurdity in the arts,’ he says in his interview.

When we met the 72-year-old K.C. Narayanan in Sreekrishnapuram last year, we found him deep in study for his new book. He was additionally learning to play the chenda melam, and demonstrated some of its intricacies during our visit. The three days we spent with K.C.N. underscored Eliot’s stand that “the critic must be the whole man, a man with convictions and principles, and of knowledge and experience of life.” With Azhagiya Manavalan as our pilot and interlocutor, we conducted our interview. Though our conversation was somewhat formal to begin with, we were happy with what we had at the end of the first day. However a new burst of vitality entered our discourse on the second day, when the four of us made an impromptu excursion to the neighboring town of Karalmanna to watch a Kathakali performance. K.C.N. pulled out old books of Kathakali aatakathas and Manavalan translated portions of Kalyana Sowgandhikam for us; the two of them gave the Mozhi team a crash course on the formal and singular language of Kathakali, its archetypes and mudras. The experience of immersing ourselves in the sound and colour of that performance shifted something in our interactions. The conversation became more free-flowing and inspired as K.C.N held forth on the osmosis between Kathakali and Malayalam literature’s critical traditions. We began to appreciate how taste is often a hyperlocal phenomenon that can nevertheless sharpen understanding and deepen artistic experience across boundaries.

On the morning of the last day we spent in Sreekrishnapuram, K.C.N. took us on a walk around the town. As we stepped out of his home, which itself was surrounded by an overgrowth of trees and creepers, our eyes immediately went to the flame-like bursts of orange and red by the roadside. It was the Krishnakreedam. It had bloomed with the monsoon rains, just in time for Onam. A wild beauty, its shape and vibrancy reminded us of the resplendent crowns that gave much character to the Kathakali costumes we had seen the previous evening.

*

The Krishnakireedam, we later learned, holds the spotlight during Onam, for it is the flower that ‘crowns’ the clay pyramidal figure of worship placed at the centre of the floral pookalam. Depending on whom you ask, the central figure could either be Thrikkakarappan or Vamana, an avatara of Vishnu; or Maveli or Mahabali, the large-hearted asura king he subdued. Whoever it might be, it is the Krishnakireedam, with its bold, unrestrained brilliance, that crowns the figure and makes a deity of either. So it is with good criticism. Without singularity, without brilliance, without boldness and beauty, it is impoverishing to talk about art.

It is this spirit that we hope to capture in this magazine. The Mozhi Criterion is our argument against dullness, against a review culture that is either bland or steeped in labels. It is an attempt to talk about literature with a passion that is afforded to life itself. In embarking on this journey, we see ourselves as students as much as we are editors or curators.

We welcome you to immerse yourself in The Mozhi Criterion. Do write to us at contact@mozhispaces.in. We look forward to engaging, debating, and growing with you.

Suchitra & Priyamvada

Team Mozhi

Interviews

“I unconsciously longed for an alternative cultural space”

An interview with writer & translator Azhagiya Manavalan

Essays