“I unconsciously longed for an alternative cultural space”

An interview with writer and translator Azhagiya Manavalan | Translated from Tamil by Priyamvada Ramkumar

Mozhi: Can you tell us a little bit about your background? How did you come into literature as a reader?

Manavalan: I came to reading quite late. It was in my undergraduate years that I was introduced to reading. I think my first brush with it was through Vittal Rao’s anthology – Short Stories of this Century – a 3-volume publication. Usually, engineering college libraries are quite terrible. Somehow, by pure accident, my college library had a few literary works. This book was in there. And Sundara Ramaswamy’s (also known as Su Ra) short story Palanquin Bearers (Pallakku Thookigal) featured in it. Although I had never read literature before, I got a taste of it in this story.

I also had a few friends in college who read – though, it was mostly Periyar or Anna’s writings. Or popular writing like Vairamuthu’s novels or Na. Muthukumar’s poetry. But, one of them was already reading Nanjil Nadan. He had read, Nanjil’s essays that were serialised in Ananda Vikatan called Theedhum Nandrum, I had great admiration for my friend’s taste, so I joined him on a trip to a book store in Erode, where I picked up Nanjil’s novel, Sadhuranga Kudhiraigal. After reading the work, I became more introspective. There was another friend who was into Sujatha’s science fiction and standalone essays; also S. Ramakrishnan’s personal essays. Even then, neither I nor any of my friends who introduced literature to me had any idea about a “literary movement” made up of authors who wrote consistently. It was only after reading Nanjil that I got a sense of the existence of such a private space, of a secret world, with people engaged in literary activities unknown to the outside world.

It was through Nanjil’s essays that I was introduced to Sundara Ramaswamy’s Oru Puliyamarathin Kadhai and Je Je Sila Kurippugal. It was Je Je Sila Kurippugal that gave me my primary literary experience. I read it in pretty much one night. The inevitable loneliness of an intellectual, his bitterness, his idealism, his perfectionism – though these aspects were set in a particular world in the novel, I was able to feel that they were also universal to the condition of an artist. The novel depicts both the positive and negative extremes that an artist’s natural traits could lead him to.

Once I read it, I wanted to meet Nanjil. I didn’t know what to do with the experience of reading Je Je. My friends had different reading interests and I could not discuss it with them. So, I called Nanjil and went to meet him at his house. In fact, he was the one who introduced me to Jeyamohan. When I met Nanjil, he was reading Jeyamohan’s Aram and recommended that I should meet him too. However, I didn’t meet him then.

Later, I got a job and came to Chennai. That was when I happened to read Ninaviyin Nadhiyil (Jeyamohan’s memoir on his experiences with his mentor Su Ra) at the Anna Central Library. I read it more because Su Ra was my favourite author. The old edition used to have a big picture of him on its cover. It was a critique, but it also revealed Jeyamohan’s admiration for him. After I read it, I called up Jeyamohan and met him when he came to Chennai. I voiced the early questions I had about literature, and whether one could engage in it for a lifetime. This was in 2014. That was how I was drawn into literature.

Mozhi: Did you read any translated fiction or nonfiction in that period?

Manavalan: Yes, I did. My college was a reasonably popular one. So we did have students from other cities. They may not have had a particularly literary bent of mind, but they had read one or the other literary text. For example, one of my friends had read Dostoevsky’s White Nights and was talking to another friend about it. When I heard that exchange, I said I would like to read it. He looked at me sarcastically, as if to say, you can’t read it so easily. That made me even more determined to read it, and it turned out to be a good experience, too. It was towards the end of my college days. I could see that it was a unique experience but I couldn’t name it as a literary experience…because that friend also used to read Vairamuthu’s poetry (laughs). He didn’t make any distinction between the two types of writing.

Mozhi: Did you read any Indian literature in translation then?

Manavalan: Not much. I had not read Kanneerai Pinthodarthal (Jeyamohan’s essays on literary works from across India) then. I don’t think it was even in print. I read Arogya Nikethanam (Tarashankar Bandopadhyay’s Bangla novel Arogya Niketan in Tamil), but it didn’t appeal to me at that time. I was only able to get into it later, after I’d read (Malayalam writer and critic) PK Balakrishnan’s perspective on it. I read Malayalam literature in translation to an extent. Thottiyin Magan (Thottiyude Makan’s Tamil translation), for instance, which was translated by Su Ra. Then, Balachandran Chullikkad’s Chidambara Ninavugal. Works like those. [Thakazhi’s] Chemmeen…again it wasn’t very inspiring for me as a budding reader. Nanjil introduced me to culturally rooted writers like A Madhavan and Jeyamohan. That appealed to me a lot more. I read Indian literature – Raag Darbari, Bangarwadi, for instance – much later.

Mozhi: Were there any readers in your family who influenced you?

Manavalan: No. My father was a reader, but not a reader of literature. He used to read Sujatha, Cho Ramaswamy’s serialised version of Ramayana in Tughlaq. I discovered later that he had collected the serialised episodes. I didn’t know that as a child. My aunt (father’s sister) used to tell me that my father, my uncle and she used to read commercial novels like Ponniyin Selvan and Sivagamiyin Sabadham when they were serialised in Kalki. They read it in turns, impatiently waiting for their chance. That was a common phenomenon in Tamilnadu, then – this was before my father’s marriage. After marriage, he had the obligations of a typical family man with a meagre income, belonging to the Indian middle class. He had literally no time to spend with me, except for telling me some puranic tales. When I was an adolescent, he passed away. So I can only imagine what his literary taste might have been. He may have been someone who had a mix of popular and serious tastes. Beyond that, I don’t think there was much of a literary introduction at home.

I was never exposed to popular media or popular tastes in my childhood. We didn’t have a cable TV connection at home, because my parents believed it would spoil our education. I would only watch cricket. I was never introduced to cinema, or other popular modes of entertainment. I didn’t have any aversion towards popular entertainment, just that I was not introduced to it. I was directly introduced to serious literature, and so I could easily distinguish between popular taste and serious taste.

Mozhi: Did you learn any language other than Tamil or English?

Manavalan: I learnt Hindi in school through the Dakshin Bharat Hindi Prachar Sabha exams. I got some taste of literature through it. Stories by writers like Premchand were part of the syllabus. There were some stories and poems that personally affected me, but I didn’t know how to categorise that experience. I remember a story called Raksha Bandhan, but I promptly forgot Hindi later.

Mozhi: Malayalam?

Manavalan: I was not introduced to Malayalam at that time. Nanjil used to write often about the Malayalam world. Especially comparing the literary milieus of Malayalam and Tamil. It was through him and later Jeyamohan, that I got interested in Malayalam.

Mozhi: How were you introduced to Malayalam culture?

Manavalan: It largely came from Jeyamohan’s fiction. The Kumari culture is embedded in my mind as Malayalam culture. I am not able to associate it with Tamil in spirit. The people, their accent, their lifestyle, and their wit, in the fictional world I was encountering, registered in me as characteristic of Malayalis. While reading Jeyamohan later on, I saw that he called them remnants of an old Tamil culture. Even so, that is how it registered with me. Then, I went on to read his essays on Malayali culture. With this background, when I started meeting Malayalam writers and Kathakali artistes, I began to unconsciously form my own conception of who a Malayali is, or what their general tendencies are, what their lifestyle is and so on. I know one can’t generalise it like that, but it happened unconsciously. Kili Sonna Kathai (A Parrot’s Tale), Jeyamohan’s novella painted a cultural picture too. As did films like Ozhimuri. All of this kindled my interest in Malayalam culture even more.

Mozhi: Did your family’s background influence this in any way?

Manavalan: I don’t think so. My father’s side is from Kanchipuram or thereabouts, and my mother from Karaikudi. Maybe one of our forefathers might have migrated from Kerala. I don’t know about that, but I had no interest in identifying my family’s roots.

Mozhi: The reason we asked is that your genesis as a translator is rather unique. Usually, translators who work between two languages are from a geographic border area (such as Kulachal Yousuf), or may have migrated for work and learnt a language. But in your case, you have no such connection. It seems to have happened exclusively out of a personal interest. For instance, you spoke about Ozhimuri.

Manavalan: Women asking for divorce is new to us. But Kerala’s culture had allowed women that liberty for ages. That piqued my curiosity and I wanted to learn more about it.

Mozhi: The other side of it is also that only in the Indian scenario do translators work out of a language which they have learnt organically. If we take translators from the West, Daisy Rockwell or Deborah Smith for instance, many of them have picked a source language that they had no prior connection with and trained themselves to translate out of that language.

Manavalan: Yes, Kamil Zvelabil is another example. He was a European, but had learnt four or five Indian languages before he even set foot in India, and had probably translated a few Indian texts by then, too. I also think that my familiarity with Hindi helped me immerse myself in Malayalam because Sanskrit is a common root in both the languages. So, there was a common vocabulary.

Mozhi: You say that Jeyamohan’s writing kindled your curiosity in Malayali culture. However, someone else might have satisfied that curiosity without really learning the language. Perhaps, by reading more works in translation. How did the urge to immerse yourself in the Malayalam language and culture develop?

Manavalan: That came from getting to know Malayalam writers. P.K. Balakrishnan for instance. His essays had not been translated into Tamil when I started my journey. Jeyamohan’s writing in Malayalam, too. Not all essays from Uravidangal, his memoir in Malayalam, have been translated into Tamil (Mozhi note: This book has since been translated into English by Sangeetha Puthiyedath: Of Men, Women and Witches). Vyloppilli Sreedhara Menon is another example. The only way I could have read him was in Malayalam. Also, I was attracted to the Malayalam script (laughs). It has something called koottaksharam, where a few letters are combined to create a compound letter. I had fun learning to write it, it felt like playing with building blocks. The letters were fluid – not concrete like Tamil. That in itself was a source of attraction for me. I imagined how one letter was trying to repel another letter, or how one letter attached itself to another. They have entire relationships with one another. It was exciting to learn.

Mozhi: How long did it take before you could read a novel in Malayalam?

Manavalan: I started reading novels within a month. The first was O. V. Vijayan’s Khasakkinte Itihasam (The Legends of Khasak). Like I said, the vocabulary was sort of familiar, thanks to Hindi. So I could read sentences within a week. And then if one is already a reader of literature, it is not difficult to get into the literature of another language.

Mozhi: Was grammar not a hurdle?

Manavalan: Not really. One of the first books I read in Malayalam was a grammar book – Kerala Panineeyam. Maybe because of that. But I had only half understood it. I did have a little trouble in the first two months but it didn’t really bother me so much. Tamil and Malayalam grammars are not as different as, say, Tamil and English.

Mozhi: So how did you make the journey from reading to translation?

Manavalan: I think I started translating almost simultaneously. I think it’s both a challenge and an opportunity that comes with learning a new language. I knew that Tamil readers would not be able to read what I was reading. I felt an urge to translate it for them, just so I could discuss those works. The first translation I did was of one of Jeyamohan’s essays in Malayalam. I translated it and sent it to a few close friends. It must have been around a month since I started learning the language.

Mozhi: So, can we say that your linguistic interest is a subset of your literary interest?

Manavalan: Yes, you could say that.

Mozhi: Asking this because you spoke about P.K. Balakrishnan. Would it be right to say that your interest in him was an interest in a particular way of thinking?

Manavalan: Yes. When I started reading P.K. Balakrishnan (P.K.B.) in Malayalam, I felt that he had 200% conviction in his ideas, as if anyone who wants to refute his ideas dare not to do so because of his strength of conviction, not because of its logical structure. His sharp criticism and cynicism towards the tendency of Malayalis to glorify their culture and tradition, combined with his sarcasm could deeply provoke any sensitive Malayali. I deeply admire his flavour of genius – it is not logical strength but the way of expression.

Infact, my admiration of P.K.B. began even before I had read him in Malayalam. Jeyamohan had written an article in Tamil about meeting P.K.B. Through that essay I developed a deep attraction for the man that went beyond his ideas. That was because, in the essay, even his mannerisms were narrated as vividly as one would a protagonist of fiction. With some personalities, their perspective on life and the way they communicate is both strange and unbearably attractive at the same time. P.K.B. unconsciously grew inside of me. I daydreamed about him all day. One of the reasons I learnt Malayalam was to read him. Only his Ini Njan Urangatte (And Now Let Me Sleep) was translated into Tamil at that time.

Yes. When I started reading P.K. Balakrishnan (P.K.B.) in Malayalam, I felt that he had 200% conviction in his ideas, as if anyone who wants to refute his ideas dare not to do so because of his strength of conviction, not because of its logical structure.

I deeply admire his flavour of genius – it is not logical strength but the way of expression.

Mozhi: We were talking about how it is uncommon for people in India to take an interest in another language or culture and learn something new. Maybe it’s just an impression we have, but it does seem to us that this inclination is much less than what we see in other societies abroad. Do you think it is a cultural weakness, that we are not able to enter another culture so easily? Is there a psychological reason that happens – maybe our traditionalist outlook, or the fact that we are already forced to learn two or three languages because of our circumstances?

Manavalan: I also feel that there is some barrier in learning a new language or getting into a new culture. But I can’t think of a specific reason for this cultural weakness. Maybe, like you mentioned, the traditionalistic outlook has a great role to play in it. Our caste system or family structures which deeply influence our psyche may be at the root of this outlook. The British education we received made us feel fulfilled in our “gumastha”, or clerical way of life. Or perhaps, it’s because, historically, Europeans were explorers and we were not. It is a point to contemplate deeply.

In my case, due to a natural repulsion, and perhaps other reasons, I had become psychologically indifferent towards the conservatism and culture that had come to me from my family. But I also felt that an individual with a sensitive, artistic bent of mind cannot be rootless. It seems that I longed for an alternative cultural space unconsciously. That’s when my interest in Malayalam culture began to flower and I started identifying myself with the classical arts forms of Kerala. All of this happened as if by chance.

I felt that an individual with a sensitive, artistic bent of mind cannot be rootless.

It seems that I longed for an alternative cultural space unconsciously.

Mozhi: How were you received by this new cultural milieu?

Manavalan: It is my impression that the average Malayali is quite a loner. You can sense discomfort in their body language even when they meet another Malayali. Generally, I did sense a bit of distance in their eyes and demeanour. I could see that some of them were surprised to see an outsider in their midst. Some people did ask me directly about it, but most were indifferent. A few asked with awe about my interest in Kathakali.

But I think it wasn’t about me. That attitude is there between Malayalis too. I remember a writer and journalist called Raghunandan who wrote a biography on V.K.N. [Vadakkke Koottala Narayanankutty Nair]. Raghunandan mentions something in his foreword. While researching for the book, he contacted many of V.K.N’s friends seeking to unearth some of their experiences with him. While they promised to share and even made an appointment with him, when they got to know that it was for a biography, they refused to let him use it, quoting one reason or the other. Raghunandan tells us in his introduction that it was their way of saying “You can’t get so close to us. These subtleties can stay between us.” This happened even though Raghunandan was a Malayali. Finally, he was able to write the book only with the general information he obtained from V.K.N.’s family. It wasn’t any feeling of ill will. But an attitude of “let the friendship stay private, why do you have to showcase it?”

But there are exceptions. Artists are always an exception. Some Kathakali critics I met were very welcoming. A connoisseur once asked me in detail how I learned to enjoy Kathakali and Malayalam. A Kathakali viewer introduced me to Kathakali artists and percussionists even when I was very shy of meeting them. After these experiences, my impression of Malayalis is mixed. The common Malayali is a loner to the core. But artists and people with an artistic inclination are friendly. Maybe there is a subtle loneliness in them, as K C Narayanan told us. But I do have an urge to understand the artists’ depths. I plan to interview some Kathakali critics and artists in future.

Mozhi: So with these sort of reactions coming at you, how did your own criteria for what you wanted to translate evolve?

Manavalan: Most of the notable classic Malayalam fiction were already translated into Tamil by the time I started out. So, the choices were naturally narrowed down. By 2018, I had read contemporary Malayalam fiction and it was not satisfying to me. So I started searching for Jeyamohan’s works in Malayalam as most of his essays in the language had not been translated into Tamil. My first translations were one of his interviews and a long speech. It evoked my interest as, contrary to the excessive admiration of Malayalam arts and culture in our literary milieu, his was a critique of the Malayalam culture and literature. I thought that is new to the Tamil reader.

Some of my earliest translations were curated by Jeyamohan. When I started out I had an urge to share everything I was reading. But then I realised that would be impossible. Also, if I did take that approach, it would only be a manifestation of my ego – I would merely be showing off how much I was reading. So I took to translating only those articles that I felt would contribute in some way to the Tamil milieu. Some of them, like Madhupal’s stories, Jeyamohan himself handpicked for me to translate. That was my only work of fiction. Generally, I selected the non-fiction essays myself. For instance, I translated a few of PK Balakrishnan’s (literary) essays. I chose not to translate his critiques on Malayalam culture as I was not sure of its relevance to the Tamil reader.

The other factor that slowed me down was my urge to produce good prose. While an average, “readable” translation is adequate for an imaginative reader, I had the desire to write good prose. That too is a manifestation of the ego (smiles). But that makes me keep editing my work and slows me down – which means that I have to make choices on what I want to translate.

The other factor that slowed me down was my urge to produce good prose. While an average, “readable” translation is adequate for an imaginative reader, I had the desire to write good prose.

That makes me keep editing my work and slows me down – which means that I have to make choices on what I want to translate.

Mozhi: How long does it take for you to translate an essay to your satisfaction?

Manavalan: I used to take a week to ten days, initially. I would work at it everyday and finish a first draft quickly. I’d sent it to my friend and fellow translator Paari, and continued to edit it in parallel. Looking back, I don’t think I should have spent more than three days on it. If you have a fundamental belief in the literary reader, you need not edit it so much. They have the imagination to transcend imperfection. What’s more, whenever I look at my early translations, I end up spotting errors in it. These days, I take around three days to translate a 10-12 page article.

Mozhi: Do you see a difference in your craft or your translation process between translating fiction and non-fiction?

Manavalan: The authors I selected — whether P.K. Balakrishnan, Kalpatta Narayanan or K.C. Narayanan — employ fiction-like prose while writing non-fiction. Their language possesses a fiction-like quality. The only pure fiction I have translated are Madhupal’s stories. I have translated some poems of Kalpatta, but haven’t put it out as I wasn’t satisfied with my own translation. I feel at present that poetry is truly the domain of the creative, more than any other genre. I have translated some. T.P Rajeevan’s love poems, for instance. I wasn’t satisfied with that either. I feel that (translating poetry) is the most challenging task for a translator. From word selection to style. I have unresolved questions on how much liberty one can take with style, for instance. Personally, this challenge is what I find most appealing to me, right now. Or prose that has a poetic touch, like Kalpatta’s. Otherwise, even if an article has a subtle and fresh idea, I’m not as excited to translate it.

Mozhi: Malayalam and Tamil are close languages. Do you think this helps you while translating?

Manavalan: Yes, similarities between Malayalam and Tamil help me a lot in translation. Since both languages have a shared ancestral Tamil language (though, some malayalam scholars don’t accept this hypothesis), there are more common words. Some words have only different prefix or suffix sounds. For example, the Tamil words naatru, naaval, nandu, naan (நாண்) become njaatru, njaaval, njandu, njaan in Malayalam. Marakatham in Tamil becomes maradhakam in Malayalam. I can think of a hundred such words. These are Malayalam words without the influence of Sanskrit. Also, some primitive Tamil words are still used in Malayalam even though they are unused in modern Tamil — ankanam, kavidi, vaatru, idavazhi, and so on. Nanjil Nadan, Sundara Ramasamy, Jeyamohan – these writers’ works which are rooted in Kumari culture naturally have more Malayalam words. I had read those works even before I started learning Malayalam. They were in my unconscious mind and therefore it needed little effort from me to find equivalent words in translation.

But, some things are unique to Malayalam. Such as constructing sentences without an object. Kalpatta does that a lot. Malayalam has a lot of short cuts like that, maybe because of the Sanskrit influence. Also Malayalam sentences have a beautiful rhyme to them. Kalpatta uses it a lot in his prose, in a very creative way. That is lost in translation. We may try to find equivalent Tamil rhyming words but the result will be a very synthetic prose. Also, Malayalam has more compound-words compared to Tamil.

While translating into Tamil, the translator has to employ their sensibility to render these things well. Malayalam also has some (seemingly) cliched usages that could be a vestige of Sanskrit, too – they still use flowery adjectives, for instance. We cannot translate it literally into Tamil. We have to chop an adjective or two. One might ask if a translator can take so much liberty with the text. The way I reason it out is that P.K. Balakrishnan is not writing it with a cliched mindset, so the translation should not come off sounding cliched.

Mozhi: True. And one is also conscious that the uniqueness in style should not be lost, correct?

Manavalan: Absolutely. Taking P.K. Balakrishnan as an example again, he generously uses English words in his Malayalam articles. And it’s his own kind of English, imprinted with his unique personality. I preserved that while publishing my translations online. But when I decided to bring it out as a book, the discussions with the editor and publisher made me think that intermittent English words would hamper the readability of translation. So, I decided to replace them with Tamil words. However, hearing PKB say முரண்நகையாளர் (murannagaiyaalar) instead of “ironist” is still strange to my ear. Murannagaiyaalar sounds like an official designation (laughs). I was not happy with it, but I still don’t know how to fix the issue.

Mozhi: Yes, it is a question of sounding modern rather than antiquated. Do you plan to translate into Malayalam?

Manavalan: I did have plans to translate Venmurasu into Malayalam sometime back. It so happened that I was asked to translate, from Tamil to Malayalam, a letter that was to be sent to KG Sankara Pillai. It was while trying my hand at it that I realised for someone to translate into a language that is not their mother tongue can be tricky. For it becomes a very conscious process. The word choices, for instance. We might end up doing a very precise translation, but it may not be a living, breathing one. That is the impression I was left with. Maybe it is my personal limitation.

Mozhi: But do you think there is a need for it?

Manavalan: Certainly. When I see Malayalam readers, I feel the Tamil literary sensibility has not reached them at all. Attoor Ravi Verma did translate some important Tamil works. At present, the poet P. Raman is translating some major works from Tamil to Malayalam. However many Tamil writers have not been introduced into Malayalam via translation. For instance, some Malayalam readers, even writers have asked me what Tamil works they should be reading. So, there is a latent need for these translations.

Mozhi: You spoke about Raag Darbari earlier. We were also talking about works like Prothom Prothishruti offline. These works were brought over by translators working directly between two non-English Indian languages. Just like you are today. But the sense we have is that this has reduced significantly over the years and translators use English as a bridge. Recently, while speaking with Malayala-Tamil translator Nirmalya, he mentioned how an English translation was used as a bridge to translate a well-known Tamil novel into Malayalam and the result was far from appealing. Do you think something systemic can be done to address this?

Manavalan: I’ve not read any Indian-language translations translated into Tamil with English as the bridge language. My sense is that direct translations are more creative than bridge translations. Therefore we simply need more direct translators, that’s the only answer. And they need to emerge organically. I know of literary readers who have organically become interested in a particular language (that is not their native tongue), just by reading translations. I have a friend who is keenly interested in Kannada literature, and that interest extended into a cultural interest, and an interest in learning their language. If there are avenues or workshops for them to learn the language easily, it will be helpful. Learning a new script is a barrier. While it was a creative process for me, it is mostly mechanical. If one can cross that phase, it is possible to learn quickly.

Mozhi: Do you have any translator idols?

Manavalan: I have read only a handful of prose-fiction translations from Malayalam into Tamil, many of which were Kulachal Yousuf’s translations. I feel he has captured Basheer’s dialect very well. I have read Madhupal’s short stories in Nirmalya Mani’s translation. It was a very lucid translation, without any awkward phrases or stilted constructions that translators knowingly or unknowingly insert sometimes. I was quite taken by it. Yuma Vasuki, too. Yuma has dealt with O.V. Vijayan’s prose in Khasakkinte Itihasam (The Legends of Khasak), which is an admixture of Malayalam, Palakkad Tamil and Islamic influences. That is something I look up to. Jeyamohan has translated many modern Malayalam poets into Tamil. My poetic sensibility was honed considerably by reading his Nedunchalai Buddhar.

Mozhi: We were talking about the differences and similarities between Tamil and Malayalam. We also know that you aspire to write original works in Tamil. Do you think being a translator has influenced you as a writer? If so, how?

Manavalan: Yes, I can say that it is through translating that my vocabulary has expanded. I have not read much classical literature. As a reader, I have grown up on modern literature. Therefore, my vocabulary is limited. So, for me, words that can be brought in from Malayalam – either intact or by creating a neologism – are enriching. Then, there’s style. I am unconsciously influenced by the writers I translate. That can be good and bad. Our internal language can unconsciously reflect the styles of the writers we translate; it may not be one hundred percent ours – that is a barrier.

Mozhi: We select the best of prose to be translated. But when we simultaneously also want to break out as writers, it does create a sense of inferiority. Either our own prose comes off as an imitation or we struggle to express what we want to express. Have you faced that?

Manavalan: Yes, a lot. When I write now, I am subconsciously comparing my writing to Kalpatta’s, all the time. Kalpatta’s is sculpted prose. You don’t want to imitate it, but it makes you self-critical of your own writing. And without a certain degree of self-criticism our prose could end up becoming an imitation of an established voice. So there are issues on both ends (laughs). But I also think this is a challenge facing any new writer who already read the masters: unconscious imitation or comparing their writing-style with the masters. The only difference, I feel, is that we translators face this issue with a greater intensity. I should also add something here: it is one thing to take inspiration from the masters, but to deliberately imitate their prose is something else. I am only talking about unconscious imitation here.

However, it’s also true that a good writer cannot evolve without taking inspiration from his predecessors. The line between inspiration and imitation often appears blurred at the time of artistic composition, this is one of the strange things about art.

But then there are positive influences also. For instance, I have read Kalpetta’s second novel Evidamividam in Malayalam. It is really challenging to translate it as it stretches all the possibilities of the Malayalam language. In the process of translation our inner-language will be expanded naturally.

Mozhi: Coming back to the topic of cultural immersion, we are truly in awe of your interest in Kathakali. Going into modern literature is one thing – it is an extension of going into the ideas and language of another. But going into an art form takes you deeper into the roots of another culture, their mindsets, even language. How did you get drawn to Kathakali?

Manavalan: I got my first taste of Kathakali from Jeyamohan’s essay கலைக்கணம் (An Artistic Moment). After I had learnt the Malayalam language and read their literature, I was asking myself, what next? I had a critical view of modern Malayalam literature, and so after learning the language, I felt that I had the weapons, but there was no war in sight (laughs).

The Malayalam novels of the realist school did not feel unique to me since I felt that similar works in Tamil that I had read were of a better literary quality. That’s when I happened to read this essay on Kathakali. I then began to watch Kathakali on YouTube, but I didn’t understand much. When I met (Tamil writer) Ajithan at the Kovai Book Festival, he’d just returned from the Kotakkal Utsavam after watching eight continuous days of Kathakali performances. As he narrated his experiences at the utsavam, I was drawn to the artform. Later, I went in search of live performances myself. Even though I hadn’t yet understood it, for it is full of complicated hand-mudras, I fell in love with it.

Kathakali-prandhu, they say. It’s a madness. Even if you don’t understand it, if you have an innate sensibility, you can’t help but be taken by it the moment you watch it live. You’ll start anticipating the next opportunity to watch it. I met Ajithan again, accidentally, at a Kathakali performance in the town of Panavali in Ernakulam district. Over the next two days, Ajithan initiated me into the mudras, the aesthetics, and other fundamentals of the artform. Then I learnt from YouTube. I’d pause at each mudra and look it up – even the trivial ones. If you know Malayalam, there are Kathakali artists who you can learn from. Peesappilly Rajeevan, for instance. He has conducted introductory workshops on Kathakali mudras, and the overall aesthetics of Kathakali. I learnt from what was available online. After that I started to identify and experience the intricacies of Kathakali, as well as the aesthetic variations between individual artists playing the same character.

Kathakali-prandhu, they say. It’s a madness.

Even if you don’t understand it, if you have an innate sensibility, you can’t help but be taken by it the moment you watch it live.

As I got into it, I wondered if the Asuric tradition is, to an extent, deeply rooted in their culture. They have a temple for Duryodhana and Sakuni, for instance; there are asuric elements in their ways of worship. The Chenda is called asuravaadhyam. Madhalam (Mridangam) is called devavadhyam. So it made me wonder about the asuric quality in the modern Malayali — of course, this is all my imagination. It might be completely baseless. But when you watch Kathakali, you’ll notice a tendency to suddenly break out of the classical mould. Like a child that escapes your attempts to pin it down, in the most unexpected way. Similarly in Kathakali, as the performance moves from refinement to refinement, you’ll witness a sudden burst of folkish energy. The satirical kathas, for example, tend a lot towards the folk. On one side it is imbued with bibathsam (disgust as an aesthetic), on the other, you have Duryodhana’s satire which is almost comic. Since modern Malayalam literature did not captivate me, I diverted my attention to Kathakali, it’s aatakathas (librettos), and then Koodiyattam and so on.

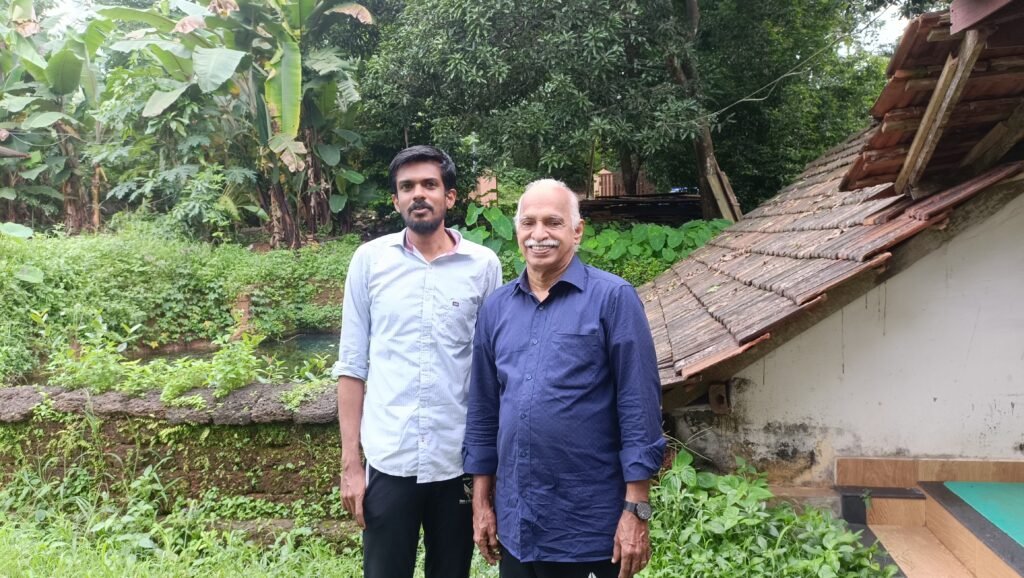

Pictures from Kalyana Souganthikam, a Kathakali performance that the Mozhi team watched in Karalmanna, Kerala

Mozhi: Were you always interested in classical arts? Wondering if you have a similar interest in Bharatanatyam or Carnatic music, for instance, which you would have encountered in your childhood.

Manavalan: Not really. I was not introduced to any of the artforms in Tamil Nadu as much, while growing up. My father had a bit of a taste for carnatic music. He used to follow the Thiruvaiyaru music festival on TV, but he hadn’t introduced it to me. I also think that if I had not been acquainted with Kerala’s culture, I’m not sure if I’d have been as interested in Kathakali. What impelled me, partly, was that I could understand the culture better if I understood this art form more. That was a driving force, more than it being a classical art form.

You’d recall KC Narayanan telling us when we met him that there’s a uniquely Malayali quality in their Kathakali critics too. For example, I quote a recent speech by a Kathakali singer: “Today more Kathakali viewers are writing about the Kathakali performances they watch. I read those writeups eagerly. More than the Kathakali performance itself, they describe the venue, they vividly describe the temple atmosphere in which the performance takes place, the history of the temple, festivals in that temple and so on. The Kathakali green room is described with utmost precision. Instead of presenting the nuances of the Kathakali performance they explain about the artists who are performing, their life, their genealogy, and their teachers’ tradition very exhaustively. How much effort is needed to collect such information and cross check them! I appreciate their painstaking effort”. Malayalis have a way of delivering sarcasm in a very matter of fact tone. This is a strong criticism of the kind of writing we see on Kathakali performances – descriptive, but unaesthetic, without a solid base of values, simply dropping a bunch of names.

For me, it is this uniqueness of expression of Kathakali that is attractive, not that classicism per se.

For me, it is this uniqueness of expression of Kathakali that is attractive, not that classicism per se.

Mozhi: When you talk about this “Malayali quality,” there seems to be an outsider’s gaze to it. But when we read your article on your experience of watching Kathakali (மாயக்கொந்தளிப்பு) where you write so passionately, it felt like the performance had struck a very private chord with you.

Manavalan: That’s innate in the artform. Even if we want to watch critically, it has the power to mesmerise you. Yes, when I step back and try to understand what drove this interest, I am able to talk critically, but when it comes to watching, I do have my own tastes, and I do worship certain artists.

Mozhi: Such as? Can you name some of them?

Manavalan: Among those who don the purusha-vesham (male characters), I like Kalamandalam Gopi for his depiction of saatvik characters (pacha vesham), Kotakkal Kesavan Kundalayar for rajasic characters (kathi vesham). Sadhanam Bhasi, who played Hanuman as well. Among those who play female characters, I like Kalamandalam Shanmughan, and Champakara Vijayakumar.

Mozhi: This is a very broad generalisation, we know, but is there something that you would classify as unique to the Malayalis vis-a-vis Tamils, as far as taste in the classical goes.

Manavalan: Hmm… I’d venture to say that even if a Malayali is not initiated into the classical arts, he can absorb it to an extent. Whereas Tamils tend to criticise something they cannot identify with. Malayalis do have a critic in them too, but they also try to understand what they are not familiar with. It’s an unconscious attitude. Also, their film music has a classical flavour — though it may tend towards the romantic. So that helps too. I feel that Tamil pop culture doesn’t have as many subtleties. They (Malayalis) are more romantic in their arts and less in real life. We have exaggerated emotions in real life but aren’t as romantic in our relationship with the arts.

Mozhi: Switching topics, it is hard to find commensurate compensation in translation, more so when you’re not translating into English. So that isn’t a motivation to pursue translation, for sure. What is your core motivator? The flipside is also that there’s an understanding today that compensation is not just about monetary reward but a way of seeking respect for one’s work. What is your view on this?

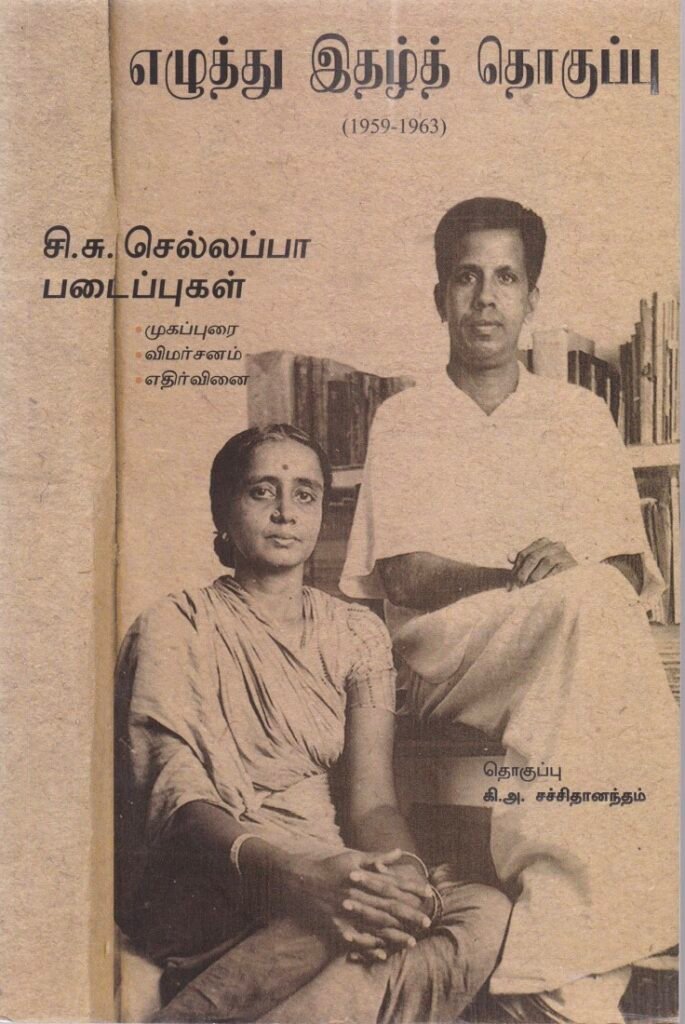

Manavalan: When you read Jeyamohan’s essays you’ll know that the Tamil literary ecosystem has never been centred around on monetary rewards…starting from C.S.Chellappa till today. Tamil literature is a non-monetary movement rooted in idealism. Both readership and monetary benefits are meagre. By understanding this, you eliminate the possibility of bitterness or disappointment when you pursue any type of literary activity. Recently, Agazh, the Tamil online literary magazine, began to offer a honorarium to its contributors for both original writing and translations. I think it came about because of the founders’ efforts to secure the right kind of sponsorship. Mozhi too, I understand now, compensates its contributors. But most literary and cultural initiatives in Tamil do not find such backing; they are not in a financial position to offer any payments. Most online litmags in Tamil offer their content for free reading. Print magazines too, aren’t monetised through sale or subscription. (Even when little magazines were in print, the founders had to invest their own money to run them.)

When I think about it, those who run literary or cultural magazines in the Tamil milieu, those who – like Mozhi – shine light on the literary heritage in various Indian languages, do so without any profit motive, and on the back of their own hard work. They give up the time they could have otherwise invested in their own individual creative pursuits. Through their efforts, they further dialogue with writers and readers. Because those who run magazines in this environment do so purely on idealistic lines, generally, writers or translators do not expect to be compensated for their works. I had this background even when I began to translate. I didn’t even think of publishing a book initially. I was just translating articles and sharing them with friends. Also, I got reactions from readers with a literary sensibility right from the beginning. So I never felt as if my work was not recognised.

Furthermore, criticism has even less readership than other kinds of writing, even in the source language. So when I translate criticism, naturally, the readership is going to be very limited. I knew that. Surprisingly, though, readers have contacted me from time to time and shared their experience. Recently, I received my share of royalty from Vishnupuram Publications for the sale of my translated work. If I consider it against the sale of literary works in the Tamil language, for a less attractive book on literary criticism, I am quite satisfied with my royalty. Though this monetary benefit can’t be compared with English translations which have a more diverse reader base.

Moreover, before I published my translation of P.K. Balakrishnan’s literary criticism, I was regularly translating the essays and sending them to Jeyamohan. He published them on his website, and this ensured that the essays got a wide readership. He also wrote the foreword for the book upon request. Vishnupuram Publications, who published the book, organized an in-person event when the book was launched. Tamil writer Vishal Raja read the book and said he was quite taken by P.K. Balakrishnan’s personality and his mode of expressing his criticism. Vishal himself has written noteworthy criticism in Tamil, so I was happy that my translation had reached the right people. After its publication, poet Shankar Ramasubramanian and writer Lakshmi Saravanakumar wrote about the book, introducing it to readers. Writer Agaramudharvan organized a reader’s meeting for the book in Chennai. To tell the truth, it is such responses that give me the encouragement to continue translating.

Mozhi: What projects are you working on now?

Manavalan: I’m translating Kalpatta [Narayanan]’s essays. I have been focusing on my own writing in Tamil, so I have been translating less these days. Also, I feel the scope to do new translations from Malayalam has narrowed since so much has been translated into Tamil already – whether the translations are good or not! The reverse hasn’t happened as much.

An interview with writer and translator Azhagiya Manavalan | Translated from Tamil by Priyamvada Ramkumar