Kathakali is a dying art form—yet, it has a strange beauty that keeps drawing us back to it repeatedly. Is it the beauty of its painting-like makeup? Its sculpture-like artistry? Or the vibrant energy of its dance? Kathakali is an art form that allows multiple ways of viewing. One can see it as sculpture or painting, or both at once. In Kathakali, the wall on which the painting is drawn, or the stone out of which the sculpture is hewn, is the human body itself.

With its large crown, the chutti on the face, the skirt-like uduthukettu, and the outer robe, Kathakali enlarges the body and transforms it into a grand, majestic form, or vesham. A tall, rounded crown, the face, made circular by the white chutti plastered underneath, the chest and arms of the Kathakali performer making a semicircle, and the lower garment again in a perfect circle—this ensemble makes up the Kathakali vesham. You could say that every costume in Kathakali is a circle—a form with no straight lines. It is upon this base shape that colours and decorations are applied to create a painting-like makeup style: the green of the face, the red of the eyes and robe, the gold of the ornaments on the chest, shoulder, and arms, and the darkness of raven hair that trails under the crown, down the back, dissolving into the inky blackness of the night.

In the flickering light of the oil lamp, these colours blend together to create an almost dreamlike experience; that is the artistic essence of Kathakali. The Kathakali vesham, which oscillates between painting and sculpture, stands motionless at times, like a deity in a sanctum, and at other times, lapses gently into movement, like a human being. Kathakali can, therefore, be defined as an art form that freezes archetypes and emotions as sculptures, and then sets them free through movement and dance.

There is an element of fragility in Kathakali. Sculptures carved from stone and paintings on walls stand the test of time. However, these beautiful, colour-sculptures carved on the human body disappear when the night fades. It is an ephemeral sculpture, an evanescent painting. The mystical stage, filled with an illusory blend of darkness and light, accentuates this transience.

Although many colours are used in Kathakali, the most prominent one is black. In other words, night. The painting-sculptures of Kathakali come to life only in a pitch dark arena. At the touch of day which ushers in the fulgor of reality, they take fright and lose their vibrancy, becoming pale and colourless. In the vast, ocean-like expanse of darkness—where a streak of light forever struggles to pierce through—the Kathakali we behold with our half-intoxicated eyes at midnight carries all the fleeting illusion and beauty of a dream. It is the drama of a dream that emerges fully adorned from the greenroom of darkness and reveals every bit of its fleeting existence to us before retreating into the same greenroom. A transient dream takes form and dances before us till it has had its fill. That is perhaps why the romantic poet P. Kunhiraman Nair who often wandered in the realm of dreams spent as much time within this particular dream.

Kathakali is a profound experience in Nair’s poetry, especially in his long poem Kaliyachan. His verses are filled with numerous metaphors from Kathakali, as if the mudras were hand gestures of a luminous world. Here are a few examples: imagining the lushness of a forest as grand Kathakali vesham (the face makeup of heroic Kathakali characters is done in green); the simile of a Kathakali artist lying down to have the chutti applied to describe a recumbent mountain; likening an artist emerging from his world of dream and expression to a Kathakali performer removing his makeup. Time and again, P. Kunhiraman Nair sees the silent dance of Kathakali as an ungraspable secret that at once informs and fascinates.

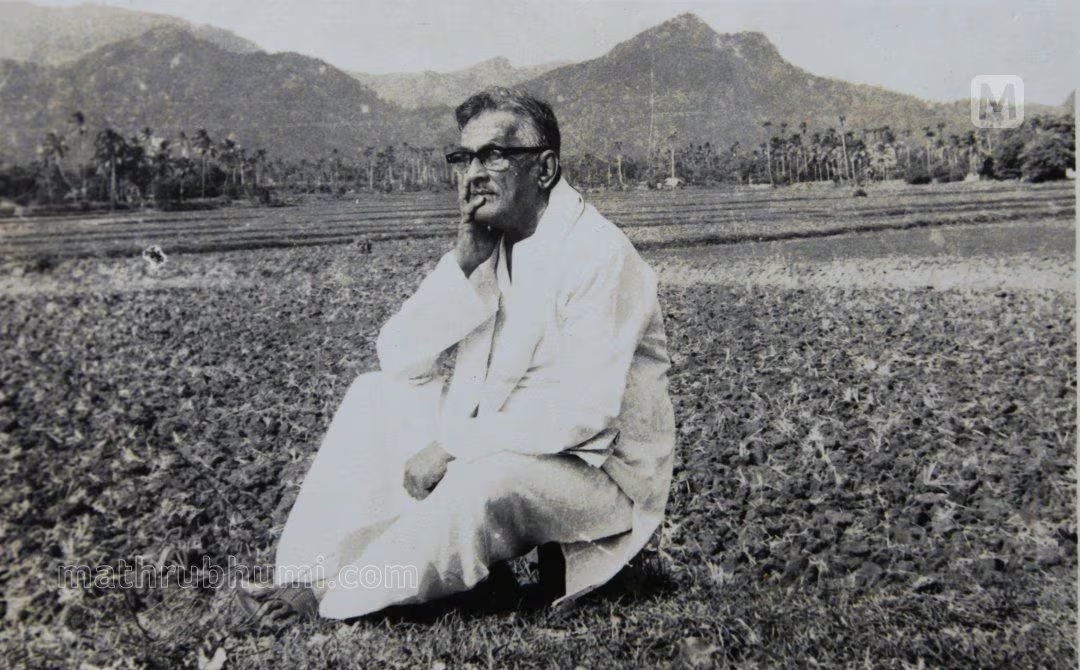

Poet Vallathol Narayana Menon revitalised the declining art of Kathakali in the 1900s with his creation of a major university-like institution called Kalamandalam. Despite his lifelong association with Kathakali, he did not incorporate even a single element of it into his own poetry. If we were to read only Vallathol’s poetry, we would not find a single line that suggests that Kathakali played any role at all in his sphere of experience. The Vallathol who lived to witness and revive Kathakali and the Vallathol who solely lived to write poetry stand as disparate as light and darkness. Why did this happen? Why is there no trace of any element of Kathakali in the poetry of Vallathol who spent his entire life in Kathakali theatres? Can it be that only those who wander in the realm of dreams are capable of seeing the nocturnal beauty of Kathakali, of life? These are questions that pique our interest in literary criticism.

Let us now take a look at how a character is created in Kathakali. Typically, certain unique elements of Kathakali instantaneously draw in those new to watching the art form—such as the tiranottam which is performed when negative characters who wear the kathivesham make their entrance. These characters stand under a large piece of cloth held above them like a canopy, and with their silver-nailed fingers slowly pull down the many-hued curtain held up in front of them. Amidst the blowing of conches and a thunderous uproar of drums, the towering and resplendent figure of the kathivesham appears like the rising sun in the tiranottam, creating an awe-inspiring moment. This is one of the most glorious and beautiful moments in Kathakali. However, this tiranottam ritual, which symbolises auspiciousness, is never performed for positive roles—it is reserved exclusively for antagonists, anti-heroes and rebellious characters.

Characters such as Rama, Krishna, Arjuna, Bhima and Yudhisthira simply enter the stage without ceremony, while villains like Ravana, Duryodhana, Kichaka, and Narakasura begin their performances only after a majestic tiranottam that may last up to half an hour. There is a strange character logic to Kathakali—virtuous, positive characters are relegated to the sidelines while extraordinary prominence is given to negative characters. This is completely contrary to the preconceptions of people who are unfamiliar with Kathakali. Many assume that Kathakali belongs to the bhakti tradition with devotion at its centre, and aligns with supremacist Brahminical ideology.

The general belief is that Kathakali is a sacred dance-drama that enacts the glorious tales of the gods. How, then, do asura characters hold such prominence? When we explore this question, the fact that Kathakali is not a product of the bhakti movement becomes crystal clear. It carries none of the devotional essence associated with bhakti. In Kathakali, not only the devas—the gods—but the brahmins are also insignificant characters. Instead, its key characters are attractive, rebellious antagonists—villains who challenge the devas, destroy brahmins, disrupt sacrificial rites, and attempt to conquer heaven.

In Kathakali, gods who vanquish these antagonists often take on roles that are puppet-like and insignificant. For instance, in Narakasuravadham (The Slaying of Narakasura), Vishnu, who kills Narakasura, is a minor character. Young performers are often cast as Krishna to familiarise them with the Kathakali stage. However, major antagonist roles, such as Narakasura, are reserved for seasoned artists like Kalamandalam Ramankutty Nair. In Bali Vijayam (The Victory of Bali), even though Bali is victorious, Ravana, who is defeated by Bali, is the central character. Many of Kathakali’s significant narratives revolve around Ravana. Stories like Kartaviryarjuna Vijayam (The Victory of Kartaviryarjuma), Bali Vijayam, Ravanodbhavam (The Rise of Ravana), and Ravana Vijayam (The Victory of Ravana) bring Ravana, the rebellious antagonist, to the forefront. In Ravanodbhavam, touted as the epitome of good Kathakali, Ravana recounts the tale of severing his own heads one by one to offer them to Brahma in exchange for boons. Ramanattam, the precursor to Kathakali, includes Ravana’s biography.

We see that light-filled, virtuous characters take a back seat in Kathakali, while dark, vengeful, and tamasic characters move to the forefront. The ancient treatise of Indian aesthetics, Natyashashtra, mandates the exclusion of war, murder, violence, blood, darkness—why, anything associated with the night from the stage. On the contrary, it is the dark, shadowy forms of the asuras that make up the central figures of Kathakali.

To understand this unique aspect of Kathakali, we must examine its origins. Kathakali evolved from Ramanattam, a performance tradition that glorified the justice, valour, and nobility of Rama. However, Kathakali shifts its focus, turning Ravana, the antagonist of the Ramayana, into its protagonist. This subversive counter-cultural element in Kathakali can be traced back even to its original text, Valmiki’s Ramayana. The final section of Valmiki’s Ramayana, the Uttarakandam, also known as Uttara Ramayana, stands in absolute contrast to the aesthetic and ethical values of the earlier portions of the epic, Purva Ramayana. Uttara Ramayana bookends Rama’s victory with his profound sorrow, diverging stylistically from Purva Ramayana.

In Purva Ramayana, Rama and the vanaras build a bridge across the sea at Sethu and rescue Sita from Lanka. In contrast, in Uttara Ramayana, the rescued Sita is banished to the forest, while Rama, Sugriva and his fellow vanaras walk into the Sarayu and disappear forever. Sita is born from the earth in Purva Ramayana, while in the Uttara Ramayana, she splits the earth open and returns to it. Ayodhya, depicted as a prosperous and auspicious city in the earlier section, becomes desolate in the latter. Rama and Lakshmana are forest dwellers in Purva Ramayana; in Uttara Ramayana, it is Lava and Kusha who wander the woods in their stead. The annihilation of the asura race is told in Purva Ramayana, while in Uttara Ramayana, the sages recount the greatness of the slain asuras to Rama. Recounting the virtues of the slain, makes the dead immortal. These stories about the asuras collectively create a profoundly critical perspective of Ramayana.

The picture of an asura clan as great as, or perhaps even more famed than Rama’s own Raghuvamsa emerges through these stories. By the end of these narratives, the strength and grandeur of Ravana, glimpsed briefly in Purva Ramayana, now grow manifold. Out of the 111 sargas or chapters in Uttara Ramayana, 35 are dedicated solely to narrating the heroic deeds and lineage of Ravana. Stories about Ravana, which are but casual references in Purva Ramayana become elaborate in Uttara Ramayana. For instance, the fact that Kubera is Ravana’s brother is only mentioned in Purva Ramayana in passing. However, Uttara Ramayana delves into the stories of their birth, how they became bitter enemies, and how this feud becomes the backdrop to the downfall of the Rakshasa clan.

Uttara Ramayana comprehensively chronicles the lineage of asuras which sprang forth from Mali, Sumali, and Malyavan, traces their defeat by Vishnu and their descent into the netherworld, the marriage of Sumali’s daughter, Kaikesi, to Vishravas, and the subsequent birth of Ravana. It also narrates in detail Ravana’s victory over Vaisravana (Kubera) and his establishment of the asura empire. Malyavan, Mali, and Sumali are scarcely mentioned in Purva Ramayana. Even Mandodari has only a minor role in Purva Ramayana, that is to mourn Ravana after his death. The story of Ravana earning boons from Brahma through penance is only briefly stated in the earlier text, whereas Uttara Ramayana narrates with dramatic intensity, the episode of Ravana offering his ten heads, one after the other, in the fire as sacrifice.

The heroic act of Ravana lifting Mount Kailasa is also absent in Purva Ramayana, while Uttara Ramayana vividly portrays his strength as he uproots the mountain that obstructs his path, and tosses it from hand to hand like a toy. It was during this episode that Ravana received the sacred sword, Chandrahasam, from Shiva. Surprisingly, a sword by that name does not even feature in the narrative of Purva Ramayana! In this portion, Ravana appears as a mere adversary who wages war against Rama, but in Uttara Kandam, he transforms into a divine figure of destruction, adorned with sacred weapons, unparalleled beauty, and supreme renown.

Seeing this from another perspective, Ravana, who fell on the battlefield in Purva Ramayana—or the canto of the Day—is resurrected in Uttara Ramayana—or the canto of the Night—with twice the valour and power, wielding ten heads and twenty arms. Attributes of beauty and valour, absent even in Rama, now seem to belong to Ravana. The Kathakali art form, which started with the intent to narrate Rama’s story, somehow culminates in celebrating the immortal deity of destruction, Ravana. Kathakali chooses Ravana instead of Rama as the human embodiment of grandeur and the figure worthy of reverence. Ravana’s colossal presence diminishes Rama’s significance. Kathakali thus venerates Ravana through performances like Ravanodbhavam (The Rise of Ravana), Ravana Vijayam (The Victory of Ravana), and Bali Vijayam (The Victory of Bali).

Among these, Ravanodbhavam deserves a special mention. Ravana is almost reborn on stage in the Kathakali artist who dramatically serves and offers each of his ten heads into the sacrificial fire, amid the adantha rhythm, one of the styles of Kerala’s tala system, which quickens and diminishes into a tight beat. The performance of Ravanodbhavam includes Ravana’s penance before Brahma, while Bali Vijayam depicts Ravana lifting Mount Kailasa. Even though Ravana is defeated in the performances of Bali Vijayam and Kartaviryarjuna Vijayam, his characterisation remains powerful. From the depths of defeat and the oblivion of death, the image of Ravana ascends with majesty and resonant grandeur, and rises through the dreamscape of Kathakali.

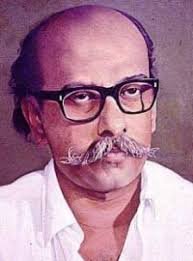

The phenomenon of situating the antagonist in the protagonist’s place is fascinating. This uniqueness is not confined to Kathakali but sometimes appears in theatrical adaptations, too. The transformation of a story beginning with Rama and culminating in Ravana’s prominence occurs not just in Kathakali but also in plays inspired by Ramayana. A good example of this shift is evident in the three plays by C.N. Sreekantan Nair that are based on Ramayana.

C.N. Sreekantan Nair’s first play, Kanchanaseeta, depicts the sorrow and decline of Rama, while his last Ramayana-inspired play, Lankalakshmi, focuses on the anguish and fall of Ravana. Not only is Lankalakshmi Sreekantan Nair’s final play, it is also considered his most mature work. Despite witnessing the deaths of his ancestors and sons on the battlefield, Ravana remains unshaken and unwavering, rising, even as death becomes inevitable, like a divine force of destruction. In Lankalakshmi, Ravana is a character who is described only in hagiographic terms. Sreekantan Nair himself notes that this character transcends the conventions of traditional epic narratives. Among all the characters he brought to life in his plays, Ravana is Nair’s grandest creation.

While the plot of Lankalakshmi is inspired by the war portions from Purva Ramayana, the characterisation of Ravana is distinct from the original. In its intricate, detailed narration, repeated references to prior stories, its character depiction and plot dynamics, the play actually mirrors Uttara Ramayana. Characters who hold little significance in the former—such as Mandodari, Malyavan, Prahastha, and Subarshvan—emerge as central figures in Lankalakshmi, much like in Uttara Ramayana.

Ravana’s marriage to Mayasuran’s daughter Mandodari, the boon he begets from Shiva, and his rise from the depths of the underworld to become the emperor of the asuras form key parts of the narrative. Ravana, with his ten heads and twenty arms, is not just an individual but becomes a representation of an entire dynasty. Sreekantan Nair’s Ravana is like a deity in a sanctum. His play is elevated by the dramatic intensity of Purva Ramayana’s war scenes. In Valmiki’s Ramayana, Ravana is not given a distinctive character during these events. Only Uttara Ramayana highlights the greatness of the asura lineage as well as Ravana’s unique traits. Sreekantan Nair draws these elements from Uttara Ramayana and emphasises them in his narrative.

Did the performative tradition of Kathakali inspire Sreekantan Nair to portray Ravana in this way? Was it the Uttara Ramayana-esque elements in Kathakali that inspired him to push the narrative towards Uttara Ramayana even while telling what was essentially a Purva Ramayana story? Lankalakshmi, the play which begins with the question “Are blood and its myriad hues as inseparable as sunrise and sunset?” is structurally not very different from the dramatic essence of Kathakali which embeds war, death, flesh, and the red of blood within it.

The three acts of Lankalakshmi culminate in the heroic mode, each time with Ravana’s valorous departure to the battlefield. In Kathakali, grand characters like Narakasura and Ravana also reach their narrative conclusions at the cusp of their departure for the wargrounds. The powerful, tender, and emotional words Ravana speaks to Mandodari in Lankalakshmi resonate closely with the padi raga of the sringarapadams, or love-songs, sung by the heroic kathiveshams of Kathakali in a moment of tenderness. In the play, the harmony of percussion instruments like the chenda and the rhythmic beats of champa talam (a tala in Kerala’s musical tradition) combine with the triumphant sound of the perumparai drum, conch shell, and the mantra “jatakataha” to evoke the emotional depth and energy of Kathakali. The resonant, thundering language created by Sreekantan Nair in Lankalakshmi brings the kathivesham of Kathakali to life on stage.

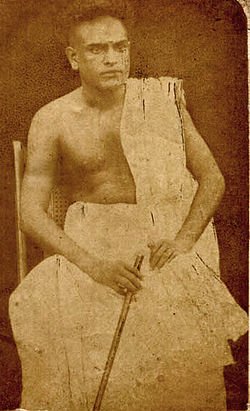

C.N. Sreekantan Nair is not an isolated figure in the cultural landscape of Malayalam art. Decades before his plays were staged, the novelist C.V. Raman Pillai emerged like a great Kathakali archetype from beyond the curtain of time. In many ways, C.V. Raman Pillai can be considered a predecessor to Sreekantan Nair. Like Nair, Raman Pillai burrowed into the past and and brought forth extraordinary heroes steeped in brilliance and grandeur from the underworld of forgotten stories.

It was with the aim of chronicling the Travancore royal family that Raman Pillai took up literature. However, art overpowered him. In his novels, the royal characters of Travancore faded into the background, and their adversaries—characters like Kaliyadiyan, Chandrakaran, Haripanchanan and other negative characters—rose as grand and vibrant protagonists.

C.V. Raman Pillai’s portrayal of the adversaries brought forth a creativity that was strangely out of reach for him when he set out to describe the kings of Travancore, Dharmaraja and Marthandavarma. His novels, which begin by glorifying the Travancore royal family, undergo a striking transformation, focusing instead on the family stories of the Ettuveettu Pillaimar, aristocrats of eight noble houses. This perverse evolution—where heroes diminish and antagonists become the focal point—can be felt by the readers of C.V. Raman Pillai’s novels. Could this continuity in aesthetic emphasis be traced from Kathakali to C.V. Raman Pillai’s novels to Sreekantan Nair’s portrayal of Ravana?

Compared to Sreekantan Nair, C.V. Raman Pillai had a deeper understanding of Kathakali and its cultural nuances. His novels are imbued with terms, references, similes, and metaphors from Kathakali. Some of the characters in his fictional world even carry the essence of Kathakali veshams or archetypes. Critics note that twenty-six Kathakali attakathas, or librettos, are mentioned in Raman Pillai’s works. It is from the veshams of Kathakali that C.V. crafts his characters. Characters like Kaliprabhava Pattan and Haripanchanan, who could’ve never existed in this world and perhaps live in an abyss far beyond the real, are the kinds of beings C.V. Raman Pillai portrays in his fiction.

Where else could C.V. Raman Pillai have drawn inspiration for the personalities of the superhuman characters in his novels if not from the symbolic Kathakali archetypes rooted in transcendental realism? In his novel Dharmaraja, the character Chandrakaran, at its peak, takes on the attire and majestic demeanour of the Ravana archetype in Kathakali. C.V. Raman Pillai introduces Chandrakaran via a recollection of Ravana’s birth, and in some parts of the novel even describes him as dasakandan, a man with ten heads.

In the final part of Dharmaraja, Chandrakaran is defeated. “O darkness, you are my salvation,” he cries out in anguish and disappears into the night; however, he does not lose himself in the dark. He emerges stronger, fiercer, and reincarnates as Kaliprabhasa Bhattan in C.V. Raman Pillai’s next novel, Ramarajabahadur. The indestructible ‘darkness’ in the theater of the gods — the Kathakali arena of the Thiruvananthapuram Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple, where the Travencore kings held sway — cannot be contained behind curtains, and roars as fiercely as a majestic kathivesham. The night and darkness are the anti-heroes in C.V. Raman Pillai’s works. We can sense how these anti-heroes transform CV’s novels into a counter-aesthetic “Ravana”yanam.

Through Kathakali, through the novels of C.V. Raman Pillai, and through the plays of C.N. Sreekandan Nair, we receive extraordinary insight about certain characters. This insight can be explained in two ways: one, that ‘greatness’ is to be found only in anti-heroes, not in mythical heroes. Or that, no matter how much they fall, it is the asura emperors and not the righteous heroes who possess a certain kind of indestructibility. It is a counter-vision that imagines attributes like greatness and indestructibility as asuraic qualities. One can call this a uniquely “Keralite” characterisation.

Deep within Kerala’s cultural fabric resides an anti-hero with asura-like indestructibility. Doesn’t the legend of Onam speak of the subterranean existence of such an anti-hero? Nowhere else does the story of the defeated find its place in the mythos of a land as it does in Kerala. Yes, an asura emperor ruled here once.

“Before history was born, before religions were born weeping, there lived an emperor of emperors, and under his grand umbrella the whole world sought refuge.” These are the words of the poet Vyloppilli Sreedhara Menon who tells the tale of such a reign. When that emperor—the embodiment of pride and prosperity—ruled, everyone was equal. There was no treachery, no thefts, no hierarchies. However, in that golden age, treachery took birth in the form of the divine. Theft was born. Hierarchies were created. A small figure adorned with a sacred thread tricked the emperor of Kerala and claimed the entire earth as his own. He subdued the emperor and stamped him down into the netherworld, much like how Vishnu once banished the Asura dynasty to the abyss. From that moment, Kerala’s paradise became the subterranean, and he who was an anti-hero to others became a hero for us. Yet, no matter how much they are pressed down, neither that paradise nor its anti-hero perish. Even when trampled and buried in the dark, they remain alive in memories and dreams, forever. Once a year, with songs and pookalams, we bring the emperor back to the surface. In a sense, this ritual is a rebellion against Brahminical dominance.

This celebration rooted in the Malayali’s mythological and cultural memory is the response of the underworld to those who dominated the whole of the earth; the response of asuras to the treachery of the devas. Our Onam declares that the defeated anti-hero is the true hero. Escaping the stark, ugly reality of the present, we journey into darkness, into the abyss of the past. From there, we craft the dream world of light and justice, the ideal world. Every Onam is a dream of Malayali culture. That dream sprouts from the womb of the earth, and blooms into onap-pookkalams, the floral carpets of Onam.

It is also an indestructible dream. Its sweetness pervades all the art forms of the Malayali. In his Kathakali, his poetry, his drama, and his distinctive storytelling, this subterranean memory takes root. On moonless nights, on the Kathakali stage, where the Brahmin is relegated to a small role while the asura dons a grand vesham, Mahabali emerges from his thiranottam with much pomp and fanfare. Every Kathakali is an Onam. It is the festival of a dream—a dream seen by Kunhiraman Nair unperceived by Vallathol. That Kathakali thiranottam transforms right before our eyes into C.N. Sreekandan Nair’s Ravana and C.V. Raman Pillai’s fierce anti-heroes.

From our nights, from our greenrooms, from our myths and memories, sweet dreams, intense moral turmoils, and visions of equality continue to emerge. As do the Ravana-veshams of C.N. Sreekandan Nair and the fierce anti-heroes of C.V. Raman Pillai. In one sense, this is the Malayali’s supreme carnival—the carnival of his magnificent memories.

Translator’s Notes:

Chutti: In Kathakali, “chutti” refers to the white facial prosthetics applied to the sides of the performers’ faces. Made from a paste of rice flour and lime, this prosthetic is crafted on thin strips of palm leaf. It enhances the size and prominence of the actor’s face.

Uduthukettu: The term “uduthukettu” describes the wide, umbrella-like lower garment worn by Kathakali performers, starting at the waist. This style creates a voluminous, circular appearance for the lower body, amplifying the performer’s overall stage presence.

P. Kunhiraman Nair: A noted Malayalam romantic poet, P. Kunhiraman Nair was a wandering soul, much like other romantic poets. Celebrated for his poetic depictions of Kerala’s natural beauty, temples, rituals, and traditional art forms, his work combines epic-like grandeur with lyrical charm. Deeply passionate about Kathakali, his poems also reflect self-deprecation, self-pity, misanthropy, and skepticism, paving the way for modernist Malayalam poetry.

Kaliyachan: Kunhiraman Nair’s long poem Kaliyachan explores the Guru-Shishya relationship in Kathakali. It delves into the turmoil, rebellion, and guilt of a student who seeks to transcend his teacher. In Kathakali, the term “Kaliyachan” is used to refer to the principal teacher or leader of a Kathakali troupe.

Kathivesham: Villainous characters in Kathakali, such as Ravana, Duryodhana, Keechaka, Narakasura, and Shishupala, are categorised under “kathivesham.” These roles serve as the foundation for Kathakali’s extensive abhinaya (expression), dance, and dramatic possibilities. The makeup for these roles features a knife-like pattern on the face, hence the name “Kathi” (knife).

Thiranottam: Refers to the ceremonial stage entry made by kathivesham characters. Since these characters, such as Ravana and Duryodhana, are often kings, their entry is marked by pomp—with silk canopies, ceremonial fans, and drumbeats. Thiranottam involves teasing the audience by partially revealing and partially hiding the character’s face behind a curtain, thereby building anticipation. The face is revealed at an unexpected moment, only to be hidden again. This alternation between appearance and concealment culminates in the full unveiling of the character’s face, followed by nuanced expressions portraying the character’s arrogance, wrath, and majesty.

Ravanodbhavam: One of the most prominent Kathakali performances focusing on Ravana, Ravanodbhavam dramatizes his origin story and his boon-seeking episode with Brahma.

Ramanattam: Predating Kathakali, Ramanattam and Krishnanattam are traditional art forms. While Ramanattam narrates the stories of the Ramayana, Krishnanattam focuses on Bhagavata. Unlike Kathakali, which prioritizes antagonists like Ravana, these earlier forms revolve around the protagonists, Rama and Krishna.

Uttarakandam/Uttara Ramayana: The final section of Valmiki’s Ramayana, Uttarakanda, narrates events such as Rama abandoning Sita to the ashram of Vasishtha, and killing the sage Shambuka. Scholars often consider this section an interpolation due to its tonal and linguistic deviations from the rest of Ramayana. Additionally, Uttarakandam contains detailed genealogies of Ravana and the Asura clan. For these reasons, it is also called Uttara Ramayana, while earlier sections are referred to as Purva Ramayana.

C.N. Sreekantan Nair: (1928–1976). A freedom fighter, writer, and dramatist, Sreekantan Nair is a prominent figure in modern Malayalam theater. His trilogy of plays based on Ramayana (Kanchana Sita, Saketham, and Lankalakshmi) stand out in Malayalam modernist literature. Among these, Lankalakshmi moves away from the traditional black-and white portrayal, and reimagines Ravana as a complex human character, delving into his virtues, doubts, vulnerabilities, and sacrifices.

Sringarapadam: In Kathakali, the initial segment of stories featuring Kathi Vesham characters, such as Ravana or Duryodhana, is called “sringarapadam.” This section depicts the characters in romantic moments with their wives, embodying the sringara rasa, or the aesthetic of love. Unlike the usually dynamic and powerful movements of Kathi Vesham, this segment is marked by gentle expressions, slow gestures, and delicate abhinaya, often set to slow Carnatic ragas, like Shree or Kalyani.

C.V. Raman Pillai: (1858–1922). A pioneer of early Malayalam novels, C.V. Raman Pillai wrote Marthandavarma and other such works based on the royal struggles and conspiracies in the Travancore kingdom. His novels intricately portray the political intrigues and resistance faced by Travancore rulers, such as Marthandavarma’s conflict with the Ettuveettil Pillamar, a feudal oligarchy.

Kaliudaiyan Chandrakaran & Haripanjanan: A character in C.V. Raman Pillai’s novel Dharma Raja, Kaliudaiyan Chandrakaran is a tax collector under King Karthika Tirunal Rama Varma. Both Chandrakaran and Haripanjanan, another member of the feudal elite, conspire to assassinate the king but fail. Chandrakaran reappears as Kaliprabha Pattana in the sequel, Ramaraja Bahadoor.

Ettuveetu Pillaimar: The Ettuveetu Pillamar refers to the feudal coalition of eight Nair families in Travancore, responsible for tax collection. Their ongoing feud with the royal family culminated in King Marthandavarma assassinating several of their leaders and exiling others. This conflict forms a significant theme in C.V. Raman Pillai’s historical novels.

An essay by K.C. Narayanan | Translated from Malayalam (via Tamil) by Aaranya Swaminathan and Suchitra