What is the relationship between Mahatma Gandhi and Madhavikutty? How did Madhavikutty, the daughter of a couple who devoted a lifetime to Gandhian values, take to Gandhism? Does her autobiography say anything at all on the topic?

Like Madhavikutty, poet and activist Sugathakumari was the daughter of a Gandhian couple. Her father was the freedom fighter and poet Bodheswaran. Her mother Karthiyayini Amma was a Sanskrit professor in Trivandrum. Sugathakumari’s husband Dr. K. Velayudhan Nair was another Gandhian.

Two of Sugathakumari’s extraordinary poems are titled ‘Corpse’ and ‘Exorcism.’ Corpse is about her act of deliberately entombing a dream-like old love. There is a schoolgirl inside her, always laughing, jumping around, often fuming, crying vexed tears, running and tripping—a young calf getting tangled in its own legs again and again. However, that girl is buried in the poem.

“‘I’ shut the lips of the little girl. ‘I’ pinched and roused that dreamy girl from her dreams, and said: ‘What a stupid fool you are! Is this what you’re supposed to be doing – whiling away your hours with dreams? And a romantic dream at that?”

The young girl’s mind is always occupied with the memory of the only face that fills her eyes. She lets flowerpetals fall one by one and fills her nights with fragrances. It’s hard, of course. But no one should know of this. Let no one know that this ‘corpse’, killed a long time ago, continues to sing songs, shed tears and sway on the swing of illusion. It’s sheer madness! Stop.

“‘I’ summoned her. Scolded her roundly. It was not enough. I pushed her into a grave. Dragged a heavy stone on top, closed it up. Stomped my feet with all my strength to make sure it was sealed tight. It was still not enough. I placed a table over the grave and kept some books on the table. I arranged some flower pots around it. Now no one shall know the presence of the grave underneath. Now I shall sit there with great dignity, carrying on with my hundred odd tasks.”

The poem called Exorcism begins thus,

“How do you do away with the mad little girl inside?”

In the poet’s own words,

“That girl, she’s my only sorrow. Truss her up! Purge her place with tears and light a lamp there. Draw the ritual circle, tie her to it. Summon the manthiravathi, let him perform the dark rituals and exorcize her of the spirits that possess her. Fasten her to a paalai tree. Drive iron nails through her breasts, hands and tongue. She can remain there. She is a nuisance, an immortal, a lover. Neither you nor I shall encounter her again. Be at peace…”

For whose benefit does the “I” in these poems engage in such intense rituals? The poem holds the answer in itself when it says, “No one should know, the world must not know.” The “I” undertakes such arduous spiritual purifications to remain hidden from the eyes of the world. The strict discipline imposed on the free spirit, the harsh penances harrowing both body and mind, the dousing of desires as soon as they get kindled within… can we perhaps attribute these temperaments to the influence of Gandhian values in her life?

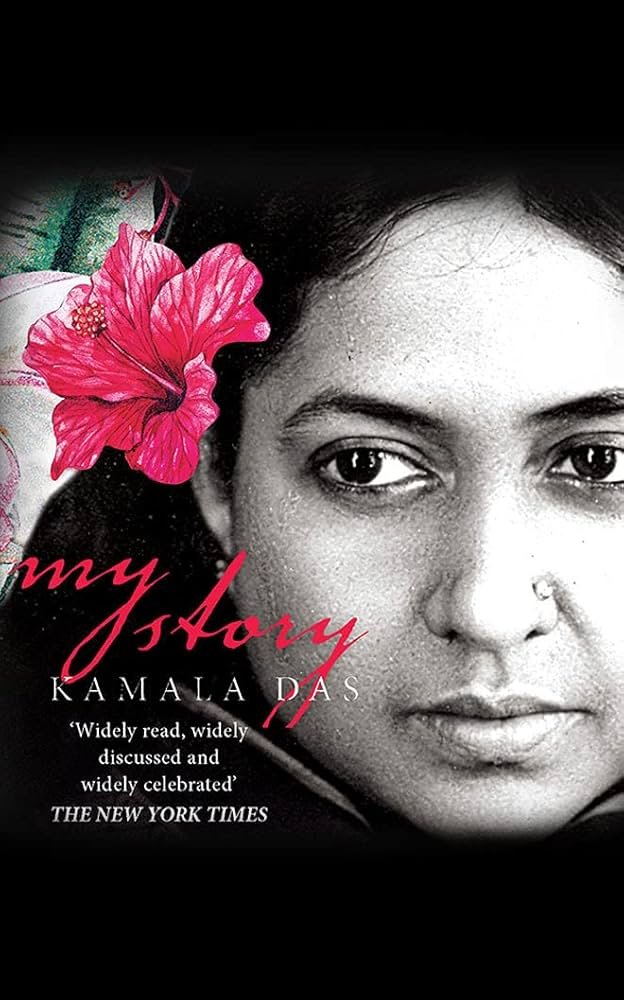

As the daughter of another Gandhian couple, Madhavikutty’s distinction, then, emerges from the fact of complete absence of any such self-suppressing, self-afflicting austerities in her life. She has no use for the funeral rites outlined in the poem Corpse. Unlike Sugathakumari who exhorts “The world must not know,” Madhavikutty proclaims. “Let the world know.” Her autobiography begins with the assertion, “I speak the truth.” Many believe her autobiography is a true account of her life while others believe that it is a blend of fact and fiction. But Madhavikutty writes, I’m going to infiltrate myself. I will ignore the many murmurs of fundamentalists, moralists and well-wishers, and pray to Sree Krishna to bestow the ability and courage to write this tale truthfully. Like Thunchathu Ezhuthachan, she’d sought the blessings of Sree Krishna to write this poetic narrative that delves all too well into her body and soul.

Poetic? Yes, Madhavikutty referred to her autobiography as a work of poetry. Her memoir is often classified as a fictitious account of real-life events or as a fabricated narrative woven from imagination. But Madhavikutty considered it a poem. “I wish to call this work a poem. When the sweet enchantment residing within the heart emerges and takes form, it does so in a structured manner – like that of prose. The words forfeit their melody. Even so, I prefer to call it a poem.”

When the whole of India was reeling under the tension brought on by World War II (note, Madhavikutty never attributed the tension to the freedom struggle in India), the shift of residence from Calcutta to the ancestral Nalapat house in Kerala and from there, back to Calcutta forms one of the key themes of the book. The notable aspect that distinguishes both these sections is the fact that Gandhi is present in both of them. Madhavikutty’s mother Balamani Amma was a Malayalam poet of note. She was one of the countless women of the time who observed Gandhian values, “like a penance” writes Madhavikutty. Her father, V.M. Nair, wore khadi at home despite being an executive in a big British motor company. Their curtains and bedspreads were all made of khadi. Nair bought only white clothes for the children whereas the mother wore only white or off-white clothes. There were very few well-to-do families who lived such a modest life in that period. “Ours is a model family. We should lead and inspire others by our humble way of living, father used to say.” The house resonated with the echoes of Gandhi’s principles.

Even at the Nalapat house, where she arrived from Calcutta, Gandhi made his presence felt. Madhavikutty writes in her biography, “…the Nalapat House had seven occupants… My grandmother, my aunt Ammini, my grand uncle (Nalapat Narayana Menon) – the poet, my great grandmother, her two sisters and Mahatmaji. ‘Will Mahatmaji approve’, whispered the old ladies of the household to one another when they undertook any new task. It was as if Mahatma Gandhi was the head of the Nalapat House. His photographs hung in every room.” Gandhi lived there as a witness and a guide to their lives. They had willingly given their gold ornaments up for him when he had visited Guruvayoor earlier. “Aunt too wore white sarees and lived a modest life.” Wherever Madhavikutty’s family was, whether in Calcutta or the Nalapat house, they embraced Gandhi’s teachings, his principles of nonviolence, his ideologies and his thoughts, with great devotion.

However right from the onset, as though she was born to parents of a different species, Madhavikutty remained outside of these ideals. She is quite candid in her autobiography about how even her thoughts and instincts as a young girl diverged wildly from those of Gandhi. She writes passionately, “I silently cursed Mahatma Gandhi who delivered my parents to a life of zealous austerity. I thought of Gandhiji as a brigand, although I did not speak my mind then.” Even at an early age, in Calcutta, one sees how she tends to be protective of her personal likes and dislikes against the dictates of Gandhism. When her parents wore white and also gave her white clothes to wear, she writes that in fact, she really wished “...to wear gold ornaments and rich, bright garments, and appear in front of guests looking like a rainbow.”

There in the Nalapat house was a man who shared her animosity towards Gandhi through his preference for distinctive clothes and meals. It was her grand uncle Nalapat Narayana Menon, poet, philosopher and the author of books like Arshajnanam and Rathi Samrajyam. Madhavikutty writes of the reverence he held within the household. He had the freedom to walk inside the house with his sandals on. “Uncle would finish his bath at 8.30. He would smile at us as he made his way, slipper-clad, to the temple. At exactly 12 o’clock, he would enter the kitchen situated in the southern part of the house to have his lunch. And what would he eat? A sumptuous meal of butter, curd, two kinds of vegetable curries, poriyal, appalam, cut raw mango pickled with a mixture of salt and chilly powder. He preferred eating solely on banana leaves trimmed along the edges. His meal duration would at times go beyond an hour and it was a treat to watch him eat, as he savoured each meal with his pale fingers and a wholesome face.”

Nalapat Narayana Menon’s meals were the sort of meals that only select upper-caste vegetarian Hindus could afford to eat daily in the 1940s. “Not just food, his choice of outfits was surprising too. He was of the opinion that women should desire opulence. His wife Kaliyapurathu Balamani Amma was seen wearing special outfits and gold ornaments almost every day. Her sweet gestures, her glittering ornaments, her fragrance imbued with the scent of Otto Dilbahar, I still remember them to this day.”

Apart from food, attire and jewels, her uncle had another peculiar trait that piqued Madhavikutty’s curiosity – his aversion to poverty. “It was his tendency to shower affection upon his sister’s children, but not towards children from other households. If any urchin happened to enter the house, he would lift his head from his book and bellow, “Go away!” He didn’t want them on his property. He believed that one should not unduly entertain the poor.” It is surprising that the broadmindedness of the man who had translated Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables into Malayalam – a novel dedicated to all the world’s poor – did not extend to his personal life. Perhaps he was simply mirroring the viewpoint of the French in the 19th century, highlighted by David Bellos in his critical analysis The Novel of the Century, that the poor should be kept in their place, that they were undeserving of pity.

Gandhi held that there was no room for extravagance in either food or clothing. He abstained from sugar. There is death in chocolate, he said. He steered clear of anything tasty. He saw sex solely as a means to beget children. He decided that in his ashram, married people would live as siblings. Love did not find a place on his list. Gandhi thought that all these indulgences stoked the passions. His was the path of Anasakti yoga—the yoga of freedom from desire.

Madhavikutty’s life, on the contrary, was outside the confines of Anasakti yoga. “I’ve often pondered how I came to be born to parents who truly embodied austerity and justice. They were impeccable, while all the perceived faults associated with femininity were conspicuous in me – a crippling fear to live a secure life, an intense longing for exquisite items and fragrances, a penchant for amusement and vanity, a tendency to worship masculine traits – a list that kept expanding.” Without a hint of guilt, she openly acknowledges her penchant for worldliness and the decadence associated with her femininity.

While this list does not speak of it, her intense fixation on the physical body often finds its way into her autobiography. “I removed my top and looked in the mirror to see my breasts taking shape. I felt content, having stumbled upon treasure…” “The first time he laid eyes on my breasts after our wedding, he fell silent in astonishment. From that moment, I held them dear and began using them as my trump card.” Recounting her first menstruation, she says, “I screamed in fear when I noticed the bloodstains on my dress. When I was left alone in the house, I stood naked and basked in the warmth of the sun. At that moment, I knew he was the male God capable of filling my womb. I felt envious of Kunti from the Mahabaratha. I desired to challenge and surpass her. I made up my own secret incantations so that I could use them to entice the sun.”

Madhavikutty did take pride in her body but as a subject of the colonial era, she resented the disapproval her body faced from the whites. In Calcutta, she had a schoolmistress named Mabel. “We were terrified of this man Archie, who visited Mabel every day to see her and caress her curly hair. He detested me for my dark skin. The school exposed me to the ugly face of racism. Teachers would place those children with golden hair and fair skin on their laps. They’d kiss them. I was never called or kissed, let alone touched by them. Standing among the white children dressed in ill-fitting white coloured clothes made me feel self-conscious about my dark skin. I believed that some evil deity had smeared black mud on my brother and I, making us outcasts. In this world of privileged white folk, I sensed that I’d forever be the one deemed cursed.”

No other female writer could better endow in words the colourism she endured during the British colonialist rule. A young Madhavikutty noticed that the discrimination prevalent in the cultural centre of Calcutta wasn’t based only on one’s skin colour but also on whether one spoke the native language or not. “I was four years old. Two tutors visited our home. A Mangalorean tutor, Ms. Sequeira would arrive at 3.30 in the afternoon to teach us English. And Nambiar, a dark man, would arrive in the evenings to teach us Malayalam. Ms. Sequeira was confident and chatted for long hours with our parents. Nambiar, on the other hand, slipped silently into the dining room and hid from my father’s sight. My Malayalam lessons would take place in the midst of the cooks. The cook served tea to the lady in a porcelain cup, while Nambiar received his tea in a glass. It appeared as if Malayalam too acquired Nambiar’s colour and his inferiority complex. My brother and I gradually developed an intense desire to outperform the English in their own language.” We know that this aspiration was realized, as Madhavikutty went on to become Kamala Das, a world-renowned writer in English.

Madhavikutty admits that from a very young age, she readily became enamoured with men and fell in love. There was no one who could answer her questions about love or desire. To learn about sex, she says she had to read her uncle’s Rati Samrajyam. Not even Mahatma Gandhi could make a final statement about love, she says. But love played a major theme in her stories. She recounts 14 love encounters in her autobiography.

Three appear in the very first chapter. “I fell deeply in love with him,” she says of the doctor who treats her. Of another lover, she says, “I got infatuated with a man who had brown eyes and a beautiful body. But I grew tired of his mannerisms and left him. When I was fifteen and started menstruating, a young man visited our home with a camera in hand. He made me stand in front of Victoria Memorial and said, ‘You are beautiful’. He later came to my wedding.” “My body was formed by such passing romances and the intense nights that I shared with my husband,” she writes. “My body is like an arena that entertains guests – a building that hosts lavish parties. Dancers danced. Musicians played. And each one of the guests sought pleasure and enjoyment.”

A life that stood starkly outside the Gandhian ethos, a body that served as a stage for dance and a birthplace of joy – her autobiography proceeds from these two stages onto a third one. This could be said to be a stage that relies, alternately, on the soul, on the body, or on poetry, and her autobiography rises towards it. The essential quest of this stage is fueled by the desire of the body, not for fulfillment, but for annihilation. “I’ve been confined, for some time, in a subconscious state to the hospital bed. Until now, twice, I have heard the pious roar of what the poets call ‘The sound of death’. By the time I hear the third call, my jittery train would have long crossed the platform. And that is why I have to write so fast.” Madhavikutty mourns this rapid pace that erodes the coherence of her work, particularly when she is in a melancholic and almost poetic state of mind.

“Today, I write in both English and Malayalam. I write with the tenacity of a leper attempting to type or weave a basket with his stick-like fingers. Scarcity of words limits my craft’s expressiveness.” Yet those limited words proliferate like stars that fill the sky. Staring at death from a hospital bed, she begins working on her autobiography My Story. She likens her impending death to death by drowning. While writing, she intermittently notices the lingering presence of death nearby. “I’ve read somewhere – one’s entire life flashes before their eyes as they drown. The memory reaches its peak as water fills the lungs.” With lungs full of water, a mind saturated with memories, eyes fixed on death, and ears resonating with death’s solemn call, Madhavikutty finishes writing her memoir post her hospital days. The third segment of her autobiography, though exuding the scent of death, shines because of the poetic metaphors it employs. Her prayer to Sree Krishna at the beginning of the book has unquestionably yielded results. She writes of her hospital room: “This is Room 565. The last time I was here, it was for my heart and lungs. People here are merciful. They are prepared to bestow the most luxurious death to the world’s biggest orphan. The snow melts on every hospital bed and the fear of death unsettles each one of the patients.”

At that moment, Madhavikutty looks back and recounts her trials for the sake of love. “I was constantly looking. I was looking for my ideal lover, the cruel-hearted one who went away to Mathura and forgot to return to his Radha. Perhaps I was seeking the brutality that lies in the depths of a man’s heart. Otherwise, why did I not get my peace in the arms of Dasettan who let me be free? Or in the intelligence of the middle-aged reader of mine? Or in Carlo who was close to my soul? Why did I shove them away and search the depths of the world in exasperation for love ? Subconsciously I hoped for the death of my ego. I was looking for an executioner whose axe would cleave my head into two.” Madhavikutty’s realm was one in which death and love were indistinguishable, where the executor and the lover were identical.

What completes life? What role does morality, love and creativity play in it? Madhavikutty explores these questions in her memoir. She writes about living a life in this world while closely observing the world of death. “Man’s greatest extent of knowledge about existence is possible when he keeps one foot in the world of the living and another in the world of death. That way, he feels balanced. The perspective he gains then is limitless, bottomless.” Such profound words! With this perspective, she discerns the shallowness within our moral codes. Our moral codes and laws are built upon our physical bodies, which ultimately undergo destruction. Whereas the timeless soul that extends beyond our body has no such limitation. “The first duty of a writer is to transform himself into a lab rat. He should never attempt to evade from the experiences that the world offers. It is his duty to document all pages of human life. Even if his body is eaten by worms and rots in the ground, in some circumstances his words shall attain immortality.” She elucidates why the words of a writer are eternal. “The writer has long exchanged rings with the future, pledging a lifelong partnership. He is not talking to you, he is talking to your children, your generations.”

To her detractors who charged her with abandoning Gandhian values and rejecting all kinds of disciplines and hard austerities, who accused her of writing wantonly and performing, in their words, a striptease, Madhavikutty had a response in her memoir. Like a dancer at the close of her final performance, removing her anklets and her elaborate costume, walking away from the stage without turning back, she writes:

“Some people told me that writing an autobiography like this, with absolute honesty, keeping nothing to oneself, is like doing a striptease. True, maybe. I, will, firstly, strip myself of clothes and ornaments. Then I intend to peel off this light brown skin and shatter my bones. At last, I hope you will be able to see my homeless, orphan, intensely beautiful soul, deep within the bone, deep down under, beneath even the marrow, in a fourth dimension. Speaking now as that soul, I ask: when I stand stark naked, stripped even of the garment of the body, will you love me?”

* Some of the quotes in this article attributed to Kamala Das have been translated from the Malayalam version of her autobiography Ente Katha. Other quotations have been quoted verbatim from My Story.

Mahatma Gandhi and Madhavikutty by K.C. Narayanan | An essay on Madhavikutty’s autobiography “Ente Katha” | Translated from Malayalam (via Tamil) by Swetha & Suchitra