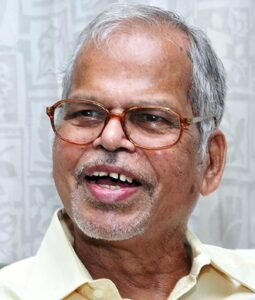

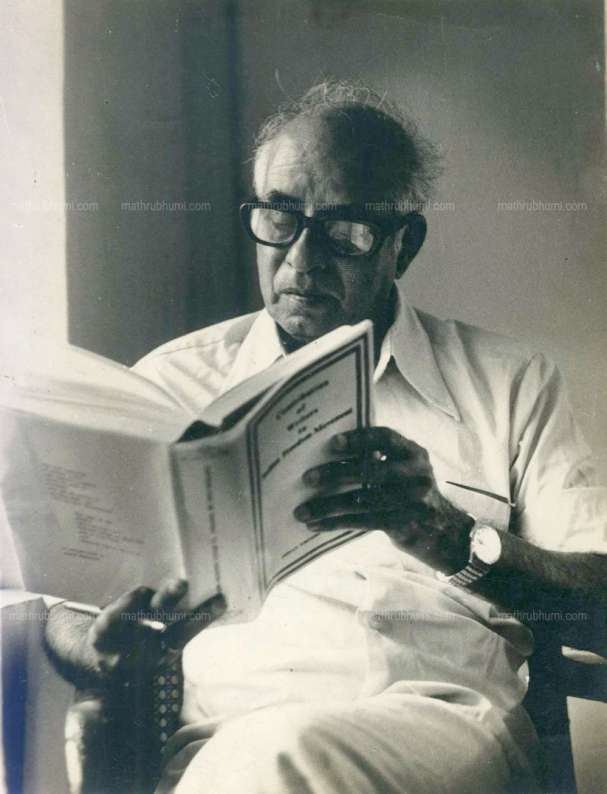

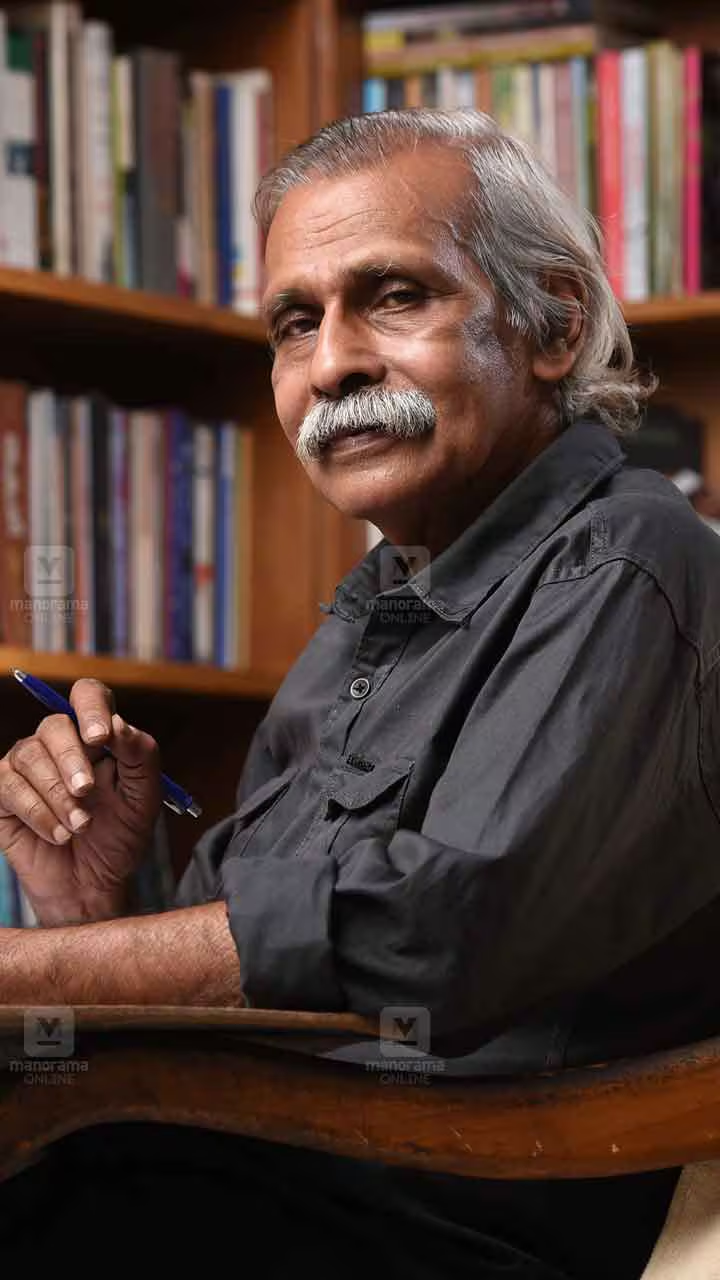

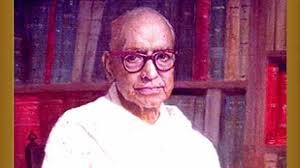

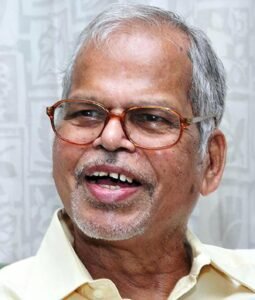

Writer & Critic K.C. Narayanan

To read this article in parts, click below:

I. Formative years & editorial life

II. Development of taste & origin as a literary critic

III. Interactions between art, culture and criticism

I. FORMATIVE YEARS & EDITORIAL LIFE

Mozhi: We learnt from a bio of yours we found online that you graduated in science and then switched to Malayalam for your post-graduate degree. How did this change come about?

K.C.N.: I was not a very sharp student. But, I still finished in the top percentile in my tenth standard board exams. That was because my fellow students got worse grades than me. Subsequently, I went to college in Mannarkkad for my pre-degree course. A senior friend of mine advised me to enroll in the group which offered biology, as that was the only way I could study medicine later. In reality, I had no wish to become a doctor—but I simply followed his advice. I scored good marks. However, the cockroach wreaked its revenge on me in my dissection practicals, and I didn’t get the necessary grades to qualify for a government scholarship. And that meant I had to pay for a medical seat. I asked my father. He refused; he said he didn’t have the money. I had brothers who were younger than me. My sisters had to be married off. In those days, Namboodiris could stave off hunger, for grains and vegetables would come from tenants. But there was no money. Sacks of rice won’t get you a medical seat, will it? My father was also worldly wise. He feared that if he did enable me to study medicine, I probably wouldn’t take care of my family once I got married. So I ended up doing my bachelors in science in Palakkad’s Victoria College. There too, I finished among the top.

The college offered Masters in Chemistry as a post-graduate course. I absolutely detested chemistry. Right from my childhood, I had nursed a love for literature. Also, at that time, Attoor Ravi Varma was serving as a professor in the government college at Pattambi. And so, I thought I’d enroll for an M.A in Malayalam. So many people scolded me harshly. Made fun of me. They said that it was very foolish of me to choose Malayalam after having scored well in science. If you’re interested in the language, you can read books on your own time, why choose to graduate in it, they said. But I stood firm and joined the course.

Within a few days of joining college, I lost my love for literature. I realised how enervating it can be to study literature as part of a formal programme. We had grammar classes, but I disliked grammar with all my heart. I even considered quitting the course. But then, Attoor Ravi Varma was around. It was in his classes that the world of literature which had, until then, been circumscribed by my own limitations, opened up. He was one of the reasons I persisted with my studies.

There was another reason. In Pattambi, there were a variety of groups outside of college which engaged with new ideas, modern artistic theories, and political thought. They were groups that wore “newness” on their sleeves. In these cliques, modernism found expression in the most acute/intense way possible. Once I began mingling with them, anything that was “old” became unbearable to me. I began to loathe poets who showed shades of traditionalism, such as O.N.V. Kurup, even though I had liked them previously. I began to worship newness. During that phase, I went in search of world literature and new ways of writing. My literary taste underwent a profound change. As far as I’m concerned, it was a turning point—my literary interest grew into a profound attachment and love. .

There were also organisations that nurtured traditional arts, primarily Kathakali and the like, within the Pattambi college. There were associations that foregrounded ancient folksongs. At the same time, there were hardened political groups, like the Naxalites, who wholly rejected the arts. Everything in Pattambi existed in extremes. It was normal to see a profound clash of ideas in a casual debate. Pattambi is one of those towns that rank high in the count of political killings in Kerala.

Mozhi: Once you finished your masters at Pattambi, you had applied to pursue a doctorate degree in Delhi. But you didn’t continue with it. What happened?

K.C.N.: The topic I had chosen for my doctorate was “Indianness in Indian Literature,” a topic that emerged from a conversation I had had with Attoor Ravi Varma. When we were talking about Indian literature, he raised the question of whether there was something that we could call Indianness. He asked if we could find something particularly Indian in our familial ties, social order, our outlook to life, or our interior worlds. To me, the subject seemed worthy of a deep exploration. One had to read all the important works in Indian literature, parse their various elements, and evaluate if they possessed some kind of Indianness. This search could lead to something that can be labelled Indian, or it could lead to nothing. The end was not important. However, one had to take a comprehensive look while researching it.

I joined the Oriental Studies programme at a university in Delhi with a letter of recommendation from scholar and professor Akavoor Narayanan. The university had a huge library. Akavoor had organised everything for me—accommodation, scholarship, the works. As luck would have it, I received a telegram within two weeks of joining the course. I had been selected for the job of Assistant Editor of Mathrubhumi. I abandoned my studies and returned to Kerala to accept the role. Given the state of my family, the job was that important to me.

Mozhi: In one of your other interviews you say that you decided not to get into academia, because it has no space for any kind of creative pursuit, and that it investigates literature as if it were a dead body. Can you explain what you meant?

K.C.N.: It is my belief that you cannot teach modern literature like you teach classical literature. We run into several problems while trying to do that. I will give you an example. “Abdhigalkkappuram chandrika paadidum apsaro veedhithan ajngaatha bhangikal.” It means, “Beauty most unbeknownst to us in the world of the apsaras where the moon sings from beyond the seas.” How do you teach this? If the students were to ask how can the moon sing, what can you say?

One can teach Kalidasa’s epics or Vyloppilli Sreedhara Menon’s poetry. To an extent, we can create a logical construct for their metaphors, emotions, metres, vision, and so on. But we can’t do that with modern poetry, not even at an elementary level. One can only teach poetry that can be converted into some logical framework.

Institutions that impart literary education are built on the belief that one can explain, and therefore teach, literature through its usage of language, its individual sentences, and its internal logic. It was this belief that allowed these institutions to flourish until the 1950s. Later, the situation changed all over the world because of two crucial revolutions.

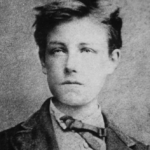

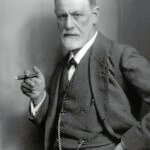

One was the symbolist revolution that originated in France of which Arthur Rimbaud was the pioneer. This camp argued that the relationship between a particular word and its meaning need not be definite, and that the experience the word evokes in our minds is its aesthetic experience. The second was the surrealist revolution—an artistic movement that was deeply influential all across the world. Just as Einstein discovered the E=mc² equation, Sigmund Freud saw “Id,” an underground world in the depths of Man’s mind. It is hard to imagine any other aesthetic perspective causing the extent of change that surrealism brought to the artistic world. The impact that Freudian thought made on man’s aesthetic outlook, mental make-up, and outlook to life is there for us to see in the works of art that followed. No other thought caused this extent of change in literature. I would call the surrealist movement an earthquake. An earthquake whose tremors were felt in literature, painting, and pretty much all art forms. What was vertical became horizontal and what was horizontal became vertical.

Mozhi: How did these revolutions change Malayalam literature?

K.C.N: Freud wrote in German. But his influence was visible across world literature, including this tiny land of Kerala. It was not only literature, but music, dance, painting—they were all seen in the 1950s as expressions of the unconscious mind. The world created by realism came to naught. Surrealism produced a realisation that the world is made up of both the real and the surreal. When you listen to this now, it might sound commonplace. Freudian thought has become that familiar. But, when it first emerged, it left a profound impact on artistic minds. Take for example, how Salvador Dali’s paintings shocked the art connoisseurs of the time.

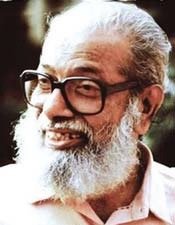

Back then, realist writers such as Thakazhi [Sivasankaran Pillai], Uroob [P.C. Kuttikrishnan], [P.] Kesavadev, and [S.K.] Pottekkatt ruled Malayalam literature. Surrealism entered this milieu through Ayyappa Paniker, and with that the sway of realism over Malayalam literature began to decline. A line in a poem he wrote in 1952 entitled The Love Song of a Surrealist (Oru Surrealistinte Premaganam) goes like this: “Frond-eyed sunbeams strummed the dance of the stars.” He depicts the eyelids as coconut palm-fronds. What is the dance of the stars? It’s not a poem that fits a given logical framework. What the words make us feel on the inside is its poetic experience. How will you ever teach this in a classroom? There is an unteachable element in poetry. The poem that I just quoted is not direct. If a reader is able to recreate those lines in their imagination, how deep that experience can be! In order to read a realist novel, it is enough if the reader enters its fictional world. However, before reading a high modernist work, there’s a need to understand the subject. Otherwise, it can seem impenetrable.

That’s why M.T. Vasudevan Nair has a wide readership, while writers like Anand [P. Sachidanandan] and Ayyappa Paniker have only a handful of readers. Once the modernist wave swept through Kerala, literary readership began to dwindle. However, many notable works were produced during this time. The symbolist revolution and the surrealist revolution engendered a sea change in literary expression and vision. That is what we refer to as high modernism.

One cannot teach that, or objectively explain the artistic experience that it offers. Understanding a modernist work is a very very private process. We land in a newness that is totally unfamiliar to us. Modernism set down roots as a powerful aesthetic movement in Malayalam literature between the 1950s and 1980s. After that, its strength waned. That was the time period in which I was born and raised. I am a child of modernism.

Mozhi: So, it seems like you gave academia the slip and entered the world of journalism! Can you share some insights from that phase of your life?

K.C.N.: I was picked for the job of Assistant Editor at Mathrubhumi when I was 23. At first I was posted in Kochi. Later, I was transferred to Kozhikode. Then, in a strange turn of events, I was offered full responsibility for the Sunday supplement. That was another turning point in my life.

The Sunday supplement became a trend setter. I ran it for six years. Around the time I got married, I was offered the role of Editor-in-Chief of Mathrubhumi Illustrated Weekly. M.D. Nalapat who was writer Kamala Das a.k.a. Madhavikutty’s son was Editorial Director then. He called me. He said he wished to appoint me to the role; if I was agreeable, he asked if I would be able to meet his conditions. He put forth two of them: One was that I should maintain the reputation of the Illustrated Weekly as the most respected publication of Mathrubhumi’s in the fields of Kerala politics, art, and culture. The second was that I should aim for a circulation of no less than 100,000 copies even though it had fallen to 70,000 at that time. I accepted his conditions. He also gave me the authority to decide the compensation to be paid to the magazine’s contributing writers. No one had been offered that freedom until then.

Even after two months of my taking up office, the sales did not improve. For some reason, the sales fell by a thousand copies every month. Nalapat called me and said they had appointed me for the very purpose of improving circulation. Keep the water boiling, he said. Now, how do I do that? I racked my brain but could not come up with a solution. Journalism is not a solitary pursuit. It is a collective endeavor. When like minded people come together, journalism thrives. I set up a brainstorming session with Mathrubhumi’s senior journalists. One of them, P. Rajan, proposed a plan. He suggested that we make a list of retired I.A.S and I.P.S. officers in Kerala, identify those who had the knack for writing, and request them to pen down their experiences. He felt that the circulation would improve if we were to publish these articles in serialised form. The serial format would create an anticipation among readers which would prop up sales, he said.

That is how we zeroed in on writer and I.A.S. officer, Malayatoor Ramakrishnan. He had given up his career to focus on writing, and settled down in Karamana near Thiruvananthapuram. I discussed our proposal with him. He was furious. I have taken oath to maintain confidentiality of office, and you want me to write about it, he shouted. I did not press further, but I wasn’t disappointed. Journalists don’t have the right to be disheartened, just like beggars. They don’t have a right to disappointment. An editor is a beggar. “Be like a beggar,” exhorts Buddha as a way to achieve a completely ego-less state. An editor cannot be egotistic.

After a few days, I visited Malayatoor Ramakrishnan again. He had softened a little. I’ll write, but only after checking with Thakazhi Sivasankaran Pillai, he said. If he tells me to write, I will, otherwise I can’t, he stated. He asked me not to approach him again on the topic. Thagazhi was like a teacher to Malayatoor. When I visited Malayatoor the next time, he gave me a little smile. Thakazhi’s cleared it, he said.

Journalists don’t have the right to be disheartened, just like beggars. They don’t have a right to disappointment. An editor is a beggar. “Be like a beggar,” exhorts Buddha as a way to achieve a completely ego-less state.

An editor cannot be egotistic.

Mozhi: Did the sale of the magazine improve?

K.C.N.: I told my seniors that he [Malyatoor] had agreed to write. We had another round of discussion. We decided to put up posters in the important towns of Kerala publicising the upcoming series—no other magazine had undertaken such publicity at that time. We printed additional copies. The sales increased by 1,000, then 2,000 and so on in subsequent issues. That was when I relaxed—I felt as if I was able to breathe again. It wasn’t just me, the entire team felt that way. That’s the way things turned out in that moment in time and we met with success. That’s all. There’s no saying that the same thing will happen again, with another writer. One cannot use this solution like a formula, all the time.

This is where the duty of an editor becomes important. First, he has to land on a subject; that is not possible alone, it has to be done as a team. Second, he has to identify a writer who can do it justice, and draw the article out of him. Third, he has to sell it. An editor has to be mindful of all three aspects in order to make progress in journalism. An editor has to sow the seed of an idea in a writer, an idea that the writer would have never thought of on his own. Once it grows, the editor may reap the harvest. The editor has to play the role of both father and midwife. All three things I stated earlier are part of an editor’s duty. I’m not saying this after studying journalism. It is what I have learnt through my work. Studying journalism is of no use. It is more a question of your innate talent. What I’m sharing here is only what I have distilled over my career, that’s all.

Mozhi: Would you say, then, that an editor’s success is founded mainly on the extent of imagination he or she brings to bear?

K.C.N.: Yes. What do you get a writer with sensitivity to write for you? An editor has to become a writer and imagine the answer to this question. One needs a great reserve of tanmayabhavam for it—that is, the capacity to identify oneself with the other. The editor has to think for the writer, not for himself. For instance, Malayatoor Ramakrishnan had never considered writing about his worklife; on the contrary, he had certain reservations about it. As an editor, I was the one who drew it out of him. But, it doesn’t end with writing, one has to take it to the world—that is what publication means. It is very close to the job of a midwife. In Sanskrit, this is known as prasuthikarmam.

In addition, there were many debates (in the magazine) on general issues. Readers began to see Mathrubhumi as more than a literary magazine. Back then, the Supreme Court had gone against the grain of the Sharia law in its judgement of the Shah Bano case. That created a big divide in Islamic society. Islamic traditionalists on the one hand and progressives on the other clashed in some fiery debates. If we had taken a stand to publish only progressive views, because we thought of ourselves as progressive, the magazine would’ve been reduced to a propaganda machine. Therefore, we published essays from Jamat Islam, and also from progressives like M.P. Mohammed and M.N. Karassery. Vaikom Muhammad Basheer wrote that men’s husbandly tools should be chopped off!

Malayatoor’s Ramakrishnan’s I.A.S. Days, the Shah Bano case—some of these general topics drew readers outside of literature to Mathrubhumi, and the readership became much bigger. Towards this, what I chose to feature was left solely to my imagination.

Mozhi: You must have met several writers during that time. Do you recall any experience in particular that left a deep impression on you?

K.C.N.: Every Malayalam writer who made a deep impression on literary readers at that time wrote for Mathrubhumi. Anand, O.V. Vijayan, [Paul] Zacharia, C.R. Parameswaran, Madhavikutty (Kamala Das), Sugathakumari—at least one of them wrote for our magazine, every week.

In the days that Mathrubhumi ran from Trivandrum, I used to meet Madhavikutty twice a week. She was such an interesting conversationalist—someone who could communicate through images. She’s an artist I’ve felt especially close to. You see an essay or a story in everything I talk about, she’d say in jest. I see that statement as a validation of my own self. More than anyone else, a good literary editor must pay keen attention to every conversation with an artist. He must have a feel for that which has potential to become a piece of writing.

She agreed to write about her school days. It was serialised in Mathrubhumi and garnered good readership. We published three essays, but the fourth never came from her. Our office had shifted to Kozhikode by then. I tried reaching her over the phone, but she was not responsive. There was no way we could’ve abandoned the series mid-way, it had such a following. I was lost. Finally, she answered the phone one day. She said that she had stopped writing those personal essays as she had doubts about whether they were being read. She also said that a woman from her neighbouring house had written her a letter, and only if we agreed to publish that in the following issue would she restart writing. The magazine itself was hers, and here she was, asking me for permission! I haven’t met any other person who was that innocent. The letter was published, and she continued to write. The series was published for a year, and then came out as a book.

I must say one more thing. I never address any writer obsequiously—I don’t use sir, madam, mashe (teacher), chetta (brother), or chechi (sister), and all that. I have great respect for their artistic mind, and some of them are very close to my heart as artists. I might have a lesser artistic sense or imagination than them, but as a journalist I am equal to them. This professionalism is very very crucial for a literary journalist. I might ask them (writers) for a piece many times, but I’m never obsequious. When a journalist stoops before writers, they stop writing for him.

Mozhi: You ditched college and became an editor. Did it afford you the freedom to become a critic later on?

K.C.N.: Yes. Had I been a college professor, I would’ve ended up as an academic critic. That is to say someone with a responsibility to write about everything. If a new novel is published, I’d have had to write a critical piece on it, or at least a review. I can’t do that. On the contrary, I like to write only about those works that leave an impact on me, and on my own time. Criticism is an act of love, one should not engage in it without feeling.

Take Arundhati Roy, for instance. When I was an editor of Bhashaposhini, a literary monthly from Malayala Manorama, we published a series entitled “The Home of Writers,” which featured essays from various Malayalam writers about their hometowns. They wrote about their birth place and their psychological relationship with it. Those who didn’t identify with any particular place wrote about their rootlessness, isolation, alienation and such, while also talking about what they intuitively ‘felt’ was home. There were 64 contributors in all. Since Bhashaposhini was a monthly magazine, we could extend this series over five years.

On the contrary, I like to write only about those works that leave an impact on me, and on my own time.

Criticism is an act of love, one should not engage in it without feeling.

Around that time, Arundhati Roy came to Kottayam for a literary gathering. I introduced myself to her as an editor, and talked about this series that we were publishing. Arundhati’s native place is Kottayam. I asked her if she would write about her experiences there. With a very polite smile, she said, I am honoured that you asked me, but I have never written so far other than at my own instigation and convenience.

Writers should truly be that way, don’t you think? They must write only what occurs to them—they must have that freedom. When she said what she did, I didn’t find any trace of pride or haughtiness in her voice. She was disarmingly candid, and yet she said it gently, with a smile. She was able to be a writer so effortlessly. A writer should write only about those things that leave an impact on him or her. A college professor can’t say that. I want to stand on the side of those like Arundhati Roy.

I cannot write about everything under the sun. And whatever it is I write about, I need a lot of time for it, I like to write at leisure. If you were to interview a college professor, you may not get much by way of new insight. It isn’t their fault, but they unwittingly get caught up in a tiresome routine after years of teaching. I feel even more energetic than you, in this conversation. I’ve expressed some new ideas in this conversation that I haven’t really thought about before. I’m getting enthused by my own words!

Mozhi: Like Kathakali artists who look into the mirror attached to the corner of their upper cloth and catch a glimpse of themselves mid-performance!

K.C.N: Nice metaphor.

Artwork by Swarna Manjari

To go to other parts, click here: I III

II. DEVELOPMENT OF TASTE & ORIGINS AS A LITERARY CRITIC:

Mozhi: Apart from being an editor, you’re also a connoisseur of art. You use the word abhiruchi (taste) often, in conversation. How did your taste develop?

K.C.N.: This house we are sitting in is called Kizhiyedathu Mana. In Kerala, Namboodiri houses are known as “mana.” Our house was not too badly off, economically. Generally speaking, there are three rungs of people in the Namboodiri community. This hierarchy has been created on the basis of three types of authority. Those Namboodiris who have the authority to perform rituals rank highest in terms of power and economic strength. Next in line are those who have the authority to teach the Vedas and conduct temple prayers. My family belonged to this second rung. Third come Namboodiris who can only conduct temple prayers. They rank lowest in power and economic well-being.

Look at this house of mine. It is a traditional house, a physical representation of antiquity. You will find the greenery that surrounds it very beautiful. Howevert, that is not the way I saw it in my childhood. The land here is ripe for cultivation, but we didn’t cultivate anything. Had it housed a Syrian Christian family, they would’ve planted rubber all around and converted it into money. Having some shade or living in a beautiful surrounding is not of importance to them. My family lived in an economic era that preceded the emergence of money. None of the systems created by money existed in it. We had no lack of grains, vegetables, dairy and other food items, thanks to what the tenants sent our way. We had enough to wear. But we didn’t have any money.

Kathakali was a regular fixture here. This village of Sreekrishnapuram has a radius of no more than 10 kilometres. But, if you walk 1.5 kilometres from this house, you’ll find three reading rooms. All three were in use in those days. Even back then, this place had a primary school and a high school. There was a big playground for football and badminton. Every youngster in town was interested in either Kathakali or theatre. Every one of them was culturally literate.

While this town was not really a leftist bastion, other than my uncle’s family and mine, everyone else supported the communist party. Our families supported the Congress. Personally, I had a reasonably good opinion of the Congress Party, too. But I did not support them. There was a bit of leftist sympathy in me. That said, I did not feel close to communist parties either. I am a modern man.

Mozhi: You spoke about the left, and Congress. How do you view Gandhism?

K.C.N.: I don’t fancy it. My instinct developed on a diet of writers like Kafka and Camus, and thinkers like Sartre and Derrida. Compared to Gandhi, it was Nehru—the man with a modern outlook—who appealed to me. It is modernity that appeals to me. Gandhi’s old-fashioned mindset always reminds me of the outmodedness ossified in my own family’s traditions. And so, I don’t find him agreeable. I found oldness intolerable. I wanted to study science in the hope that it would liberate me. I thought that modern literature and city visits would rescue me from the stranglehold of tradition.

Mozhi: How did you take a liking to Kathakali which is essentially an old artform when you abhor the old so much? How did it become an artform that you feel so close to?

K.C.N.: I see Kathakali as very much a part of my reality, just as I would the nature all around me—the mango tree and other creepers and climbers in this place. I saw Kathakali through the lens of my modern literary sensibility. The way my father or my ancestors saw it was totally different. I remember this time when I was watching Kathakali as a child, as part of an utsavam, a temple festival—the absurdity in this world struck me out of the blue, like a cloud crashing down on me from the skies. How much emptiness there is in this world! How absurd is Kathakali, and so also, every festival, every celebration. An utsavam is nothing but a trickery of your mind. I’m not exaggerating. When you think about it, how meaningless they all seem. A few years ago, when I was badly ill, I felt a sense of relief—because death was nearing me. Absurdity is so real, you can feel it so distinctly. I didn’t inherit it from existential Western literature or philosophy. It is a feeling that sprung in me very organically when I was young.

Mozhi: What is this absurdity you are referring to in Kathakali? Can you explain?

K.C.N.: Look at the stage the morning after a Kathakali performance. The emotions, colours, attires, looks, sounds, tears, blood, laughter, light—all those things that filled the night—we cannot find even a slight trace of it in the empty stage the next day. Nothing remains. The actors have shed their guises—their crowns, their colourful outfits. Those artistes have become like us. The Kathakali we witnessed the previous day was so real. But it no longer exists during the day.

That is why I’m always left with a feeling of sadness, of being deceived, whenever I’m at a festival of any kind. Everything that we watch and enjoy comes to nothing. Is it to achieve that feeling of cheatedness that I participate in a festival, that I watch Kathakali? All the same, we keep going to these events that sprout one day and disappear the next. This aspect of life keeps burning inside me. That feeling is there in me all the time. Just as sewage journeys alongside a road. My perspective on life is much like that. That is how I see human relationships too.

What I just said is one of the reasons I read existential works. When I read Camus, I felt like he was telling my story, I felt so close to him.

Mozhi: Your essay collection The Malayalis’ Night features cultural essays and literary criticism. When did you start writing?

K.C.N.: Even though I wrote a few essays when I was in college, I didn’t think of them as “real” essays. When I joined Mathrubhumi, I wrote an essay entitled “Bhagavad Gita – A Criticism.” Little magazines were thriving in Malayalam back then. I wrote small articles for them.

Mozhi: Did you not anthologise them?

K.C.N.: No. “I” am not there in those essays. They were written for the sake of literary altercations or to provoke readers. For instance, in the essay “Rejection of Love,” I argue that love is individualistic, that an individual’s love is always biased, and so love can never be egalitarian, that there can never be an “equal” love. I went on to conclude that, for this reason, love cannot be held as a social value. Whether that argument was right or wrong, I wrote it because of some inner stirring. My objective was not only to write the truth, but to write the truth in a way that would provoke the reader. My stance might be wrong but it needs to evoke something in the reader. That is the reason behind the polemical tone in my essays.

Mozhi: Do you think of yourself as a writer?

K.C.N.: I cannot write a novel. However, I can put forth my opinions in a creative manner. The essays that I did put out as books exhibit an imagination that stands on par with the fictional works of any good writer. Ideas and observations that contain the potential for imagination are equal to a fiction writer’s inventiveness.

The essays that I did put out as books exhibit an imagination that stands on par with the fictional works of any good writer.

Ideas and observations that contain the potential for imagination are equal to a fiction writer’s inventiveness.

Mozhi: Attoor Ravi Varma was your teacher. How did he influence your taste?

K.C.N.: Attoor was the first to point out the error in trying to look for meaning in a poem. We have had a scientific education. Our world is made up of ideas. Therefore, when we read a poem we automatically search for the ideas embedded in it. However, what poetry offers is an experience that cannot be converted into concrete ideas, and so, to read poetry is to reach that experience. Attoor was the one who made me realise that. It’s not such an easy thing to master. It is only when we read poetry consistently that we become readers who can exclusively enjoy the experience that it offers. Once this realisation dawned on me, I went back and read the poets I’d already read all over again. The world of poetry became much closer to me.

Mozhi: Who are the poets you like, in Malayalam?

K.C.N.: I prefer modern poets to older ones. I like N.V. Krishna Warrier. My first essay was about his poetic oeuvre. Among modern poets, I have a great love for Ayyappa Paniker. But I like a number of modern poets aside from him too.

Mozhi: Do you have an interest in classical Malayalam literature? Any particular poets you like in that tradition? In one of his essays, P.K. Balakrishnan claims that if one were to look at classical Malayalam literature, with the exception of Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan’s oeuvre, most works are not very creative. His criticism is that they focus only on language-play and are pre-occupied with shringaram or erotic sentiments, among all the emotions possible in art. What do you think of it?

K.C.N.: More than a literary quality, it is bhakthi that dominates Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan’s works. In Cherusseri [Namboothiri]’s Krishnagatha, you’ll find both bhakthi and shringaram. I, too, had the same opinion as P.K. Balakrishnan. But upon rereading, I found “my” poets. Among poets of the classical mould, I like Poonthanam Nambudiri. Even though he employed traditional prosody, I must say that I haven’t read a finer existential poet. Through my reading, I realised that one cannot judge classical poetry with the measures we use for modern poetry, and that its literary quality is exhibited in a different way. For instance, Venmani [Vishnu] Nambudiri’s language alone lends a literary quality to his works.

The Bhakti period, i.e. the period of Azhvars and Nayanmars, played an important role in classical Tamil literature. But Kerala’s bhakthi period was not as pronounced. One of the reasons was that Namboodiri Brahmins had no devotion. Their tradition was steeped in customs. It was a Poorva Mimamsic school of thought that followed only that division of the Vedas that foregrounded ritual sacrifices and other ceremonial acts, that is the karma kandam of the Vedas. As per Namboodiri custom, to propitiate a deity was a kind of wizardry; it was nothing more than the offering of ritual sacrifices. If one performed whatever prayer was reserved for a particular deity, you would reap the corresponding reward. That is all.

The presence of bhakti requires a foundational philosophy. It would be more apt to call it a mindset, rather than philosophy. It is a state of feeling fiercely close to, or fiercely detached from, God. Closeness and detachment, both are centred around God. Without the focal point of “God,” bhakti cannot exist. But rituals do not have this focal point. There needn’t exist a particular god for a ritual. If you perform the required rites (karmas), you’ll be rewarded for it, like magic. In a way, science also functions like this, doesn’t it? Science is made up of formulae. If hydrogen and helium combine in a certain proportion it will produce a sun. We can keep listing such equivalences.

What’s more, if a particular yagam or ritual sacrifice does not yield the expected result, the ritualistic person neither doubts the practice nor ridicules it. They placate themselves with the idea that they must have committed an unwitting mistake in the various steps prescribed for the ritual. It is impossible for man to replicate any activity a 100% right, and that applies to yagams too. Therefore, the result will never be 100% – that is their belief.

Given this disposition, it were the non-Brahmin Sudras of the fourth varna who were able to achieve that depth of devotion we call bhakti-bhavam. They were the ones who forged the semblance of a bhakti movement in Kerala. They were also the people who created, to the extent possible, a Malayalam language that was free of Sanskrit. Adhyatma Ramayana, a classical text composed by Thunchaththu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan in the 16th century has a greater devotional flavour than Valmiki’s Ramayana. Non-Brahmins did not have the right to read Sanskrit puranas. Since Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan adapted Valmiki’s Ramayana into Adhyatma Ramayana and brought it into Malayalam, common people were able to read it, or listen to it being sung.

Similarly, the non-Brahmin communities were the ones who spearheaded the development of spiritual traditions in Kerala. Narayana Guru is one such example. Chattampi Swami, Vagbhatananda, (Thycaud) Ayyavu Swami, Vaikunda Swami were his predecessors in the Vedantic path. Traditional medicine, too, was nurtured by Ezhavas. Literature, spirituality and medicine—all have a long history of non-Brahmin pioneers in Kerala. It was from this non-Brahmin tradition that modernism took root in Kerala.

Mozhi: Malayalam was born out of Ezhuthachan’s pioneering classical works, his Ramayana and Mahabharata. In the same period many works were also written in Manipravalam—a mixture of Sanskrit, Malayalam and Tamil. Can you comment on them? What is their role in the development of modern Malayalam literature, when compared to Ezhuthacchan’s works?

KCN: The majority of those works dealt solely with the theme of sringara, or erotic-romantic love. The bhakti bhava or devotional sentiment found in Ezhuthacchan, and the subtle emotions essential to literature were absent in them. However, there was a literary quality to that language. It was by standing within that linguistic mode that Ezhuthacchan was able to compose his classical works.

Mozhi: After Ezhuthachan, what was the next significant turning point in the development of Malayalam literature?

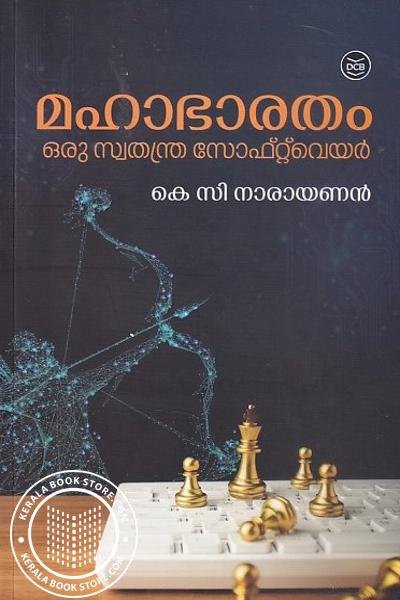

KCN: I would say, Kodungallur Kunhikkuttan Thampuran’s translation of Vyasa’s Mahabharata into Malayalam. The translation was completed at the turn of the 19th century. At that time, the Mahabharata was not taken seriously, nor was it properly understood by the few who did read it. But the freedom struggle had such a profound impact on how the Mahabharata was read. It was during this time that Kunhikkuttan Thampuran’s Mahabharata gained prominence.

One can view the Indian freedom struggle as an allegory of the Mahabharata. Just as the Kauravas deceitfully usurped the Pandavas’ kingdom through the game of dice, the British exploited and ruled over us. Regaining our nation from them was, like the Mahabharata, a dharma yuddha—a righteous war. During the election campaigns that followed Independence, political parties would often say, “We will meet in Kurukshetra.” What they meant by “Kurukshetra” was modern India. Thus, the Mahabharata came to function as an allegory.

In Kerala, it was Kunhikkuttan Thampuran’s Malayalam translation of the Mahabharata that made the epic a part of public consciousness. Following that, literary critic Kuttikrishna Marar wrote Bharata Paryadanam, his reflections on the Mahabharata in essay form. Even today, it remains an important work in Malayalam literary criticism. In addition, other reimaginings of the Mahabharata were written, such as P.K. Balakrishnan’s Ini Njan Urangatte (And Now Let Me Sleep) and M.T. Vasudevan Nair’s Randamoozham (Second Turn). Furthermore, P.K. Balakrishnan also wrote a critical work titled Ezhuthachante Kala (Ezhuthachan’s Art), in which he compared the Mahabharata written by Ezhuthachan in Malayalam with the Vyasa Mahabharata. Though I do have my criticisms of that book, it is a noteworthy work.

My own Mahabharatam: Oru Swatantra Software (Mahabharata: An Open-Source Software) is one of the more recent creations in that line of works.

Mozhi: Among the books mentioned above, which one inspired you to write your book on the Mahabharata?

K.C.N: I have read Marar’s Bharata Paryadanam. I have also read the various re-narrations of the epic written in Malayalam. But when I decided to write down my observations on the Mahabharata, I deliberately made myself forget all the readings of the epic I had encountered until then. I read it directly. I wanted to write exclusively about the impact that that particular text had on me and what I discovered through it. I believe I have, to some extent, succeeded in doing that in my book.

That act of “forgetting” was essential to ensure that my work was new, not an imitation, and was free from the influence of other interpretations. Perhaps traces of influence from earlier thinkers may have unconsciously found their way into my observations. But, consciously, I sought only to present my own self and what I had discovered.

Mozhi: Which readings of the Mahabharata in Malayalam would you say are close to your perspective?

K.C.N: Not just with regard to the Mahabharata, but in all matters related to art, my perspective is fundamentally aesthetic. I find the aesthetic outlook of poets like Kalpatta Narayanan and T.P. Rajeevan congenial to mine. Among critics, the perspectives of M.P. Sankunni Nair, V.T. Rajakrishnan, and K.P. Appan are ones I feel close to.

In Kerala, the Marxist view dominated art criticism. To use their term, it was a hegemony. Since they also held political power, their side was strong. The aesthetic perspective stands in direct opposition to that approach. For instance, pioneers like M. Govindan and Attoor Ravi Varma consistently upheld an aesthetic approach that opposed Marxist aesthetics.

Marxist art criticism investigated the ideas they believed to be embedded in works of art, and the political ideologies underlying those ideas. This is a rather flat, simplistic way of looking at art. Because of this approach, they were compelled to reject most artists. They did not accept poets like Akkitham Achuthan Namboothiri and Vailoppilli Sreedhara Menon, who worked in the traditional style. Even the modernist novel (O.V. Vijayan’s) Khasaakkinte Itihasam (Legends of Khasak) was not acceptable to them. Nor were modernist writers like M. Mukundan and Anand, or realist novelists like Thakazhi [Sivasankaran Pillai] and Kakkanadan. The whole of Malayalam literature was regressive according to them.

Between the 1950s and the 1980s, a season of high artistic creativity emerged in all forms of art in Kerala. That period is a crucial one in the history of Kerala’s arts. In literature, modern poets and novelists who broke away from traditional forms came to the fore. In Kathakali music, there was a creative energy and innovation like never before. A new wave of realist aesthetics emerged in Malayalam cinema. Some of the finest modern plays in Malayalam theatre were created during that period. Temple-bound art forms like Koodiyattam, once performed only by specific castes, became art forms anyone could learn in public spaces. So many transformations occurred—yet Marxist art critics in Kerala did not accept any of it. Using various critical vocabularies, they declared all these changes to be regressive.

It is necessary to point out a particular nature or limitation of aesthetic criticism. Aesthetic criticism cannot establish the artistic quality of a work. It simply offers a few observations arising from the critic’s own aesthetic experience and shares them with the reader. It can only speak to those who are willing to accept at least a little of that experience. For example, if I say M.D. Ramanathan is a great singer, I speak of the unique qualities I perceive in his music. If you accept some of those qualities and disagree with some, we can have a conversation. But if you say, “M.D. Ramanathan is not a singer at all,” then it becomes impossible for us to have a discussion. Aesthetic criticism cannot justify itself or prove that M.D. Ramanathan possesses artistic value. Can one point out the qualities of light to someone who firmly believes that light does not exist? The experiential truth we arrive at through art cannot be proven through argument or counterargument. That is why, in Kerala, the critics of the aesthetic school were not able to engage in dialogue even at a basic level with the Marxist critics.

Aesthetic criticism cannot establish the artistic quality of a work. It simply offers a few observations arising from the critic’s own aesthetic experience and shares them with the reader. It can only speak to those who are willing to accept at least a little of that experience.

Can one point out the qualities of light to someone who firmly believes that light does not exist?

Moreover, because the Marxist critical tradition was such a strong ideological force, aesthetic criticism was always compelled to point out the flattenings and simplifications in the Marxist critical perspective. That was because aesthetic criticism was inherently a creative attempt that emerged in opposition to such flattened, simplified perspectives of art.

Mozhi: You have written a critical essay on the novel Naalukettu. Moreover, in a private conversation, you also spoke about what you learned from M.T. Vasudevan Nair during the early stages of your career as a journalist. Did your personal relationship with M.T. Vasudevan Nair in any way shape your reading of his novel or your criticism?

K.C.N: No, not at all. My criticism was written entirely based on what’s in the novel itself and what it gave me during my reading. My familiarity with M.T. Vasudevan Nair or his personality played no part in that.

Mozhi: But in your essay on Madhavikutty, you have used elements related to her personal life, haven’t you?

K.C.N: I was on good terms with Madhavikutty; we’ve spoken about many things. But in my essay, I present observations related to her personal life based solely on what she wrote in her autobiography Ente Katha (My Story). Even if I had not known her personally, I could still have written that essay, purely based on her autobiography.

Mozhi: In literary criticism, how important do you think it is to know the writer’s personal life and individual personality? Do you believe in biographical criticism?

K.C.N: For me, the writing is enough. Whatever I may have heard about the author or know from personal acquaintance is not necessary. My position is: “the text contains everything.” Whether the work is an autobiography, fiction, or essay, one can read the writer’s intellect, emotional shifts, and leanings in the writing itself. His inner self is imprinted in the text without his conscious knowledge — as subtext, inscribed, superscribed, or subscribed in it. He may try to hide that self, to superimpose on it, or to write in the guise of complete openness, but his interior self will inevitably come through; he cannot keep it concealed. That is the first tenet of my literary criticism: “the text contains everything.” Literary criticism must discover the writer’s soul within the text and point it out to the reader. That is why good criticism can give an experience as intense as the literary work itself.

Mozhi: How did you develop this style of criticism? Do you have any role-models?

K.C.N: I have read many literary critics and have debated with some of them. I’m afraid I cannot point to any one person definitively as my role model. It is an aesthetic perspective that began forming during my college years. Primarily, it developed as a response to the Marxist literary criticism I encountered. Marxist critics tend to speak not about the literary text itself, but about the subject matter of the work and its class structure. I attempted to align myself with the Marxist position, accept its aesthetics, but I couldn’t.

Mozhi: Which literary critics do you feel closest to?

K.C.N: To answer that, I need to speak a little about the history of Malayalam literary criticism.

The literary criticism that is closest to my aesthetic perspective is that of P.K. Balakrishnan. Works like Novel Siddhiyum Sadhanaiyum (Fulfillment and Achievement of the Novel) and Kavyakala Kumaranasaniloode (Art of the Epic: Through Kumaran Asan) are critical texts I greatly appreciate. He was also a leading figure of historiography in Kerala. In my youth, I wanted to become a writer like him. He wrote a book comparing Vyasa’s Mahabharata with the Ezhuthachan’s Mahabharata. That book, however, is the one I do not find appealing—it is the shallowest among his works. For someone who knew so much history, he ought to have examined the period in which Ezhuthachan emerged against the backdrop of Indian history. But he did not do that.

Mozhi: In a conversation, Jeyamohan mentioned the word aswadanam, meaning appreciation. That is, a form of writing about a text that is neither a review nor critical essay, but something else. In Kerala, he mentions that tradition as represented by Attoor Ravivarma, Kalpatta Narayanan, and yourself. Could you speak about that?

K.C.N: Two people can be cited as early pioneers of the aswadanam tradition in Malayalam: K.P. Sankaran and M.P. Sankunni Nair. M.P. Sankunni Nair wrote excellent aswadanam-style appreciations of Kalidasa’s epics. Kalpatta Narayanan’s critical essays can be seen as the contemporary form of that tradition. I too belong to that tradition. Their aswadanam is limited to the literary domain alone. But I have moved beyond that—to include elements related to the period in which the text’s fiction unfolds, to history, and to social dynamics as well, and incorporated all of these in my criticism.

In Malayalam, numerous works of criticism are available on any given writer. Tamil does not have as much, in comparison. But, in reality, of the great volumes of critique written in Malayalam, very few are truly of value. For example, most of the critical works on Kumaran Asan are of the level of classroom notes. Some books attempt to read into his work through lenses like feminism or Hindutva. The only truly meaningful literary critical work on Kumaran Asan is P.K. Balakrishnan’s Kavyakala Kumaranasaniloode (Art of the Epic: Through Kumaran Asan).

Every good work of literary criticism will bear the critic’s fingerprint. I came to realise that my own fingerprint was imprinted on Madhavikutty’s fictional world through readers’ responses to my critical essays on her work.

Mozhi: What should a reader gain from a work of literary criticism?

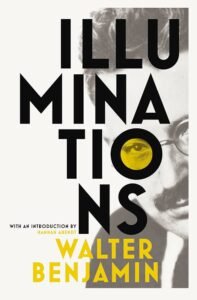

K.C.N: Like light in a dark room, criticism should illuminate aspects of a work that the reader has not previously identified. The very title of Walter Benjamin’s celebrated book is Illuminations. Moreover, through its language, imagination, and thought, criticism should deeply affect the reader and inspire them—reveal things that are not apparent in a first reading of the work. This is my measure of what makes good criticism.

Mozhi: Can literary criticism create the impetus for works that are to emerge in the future?

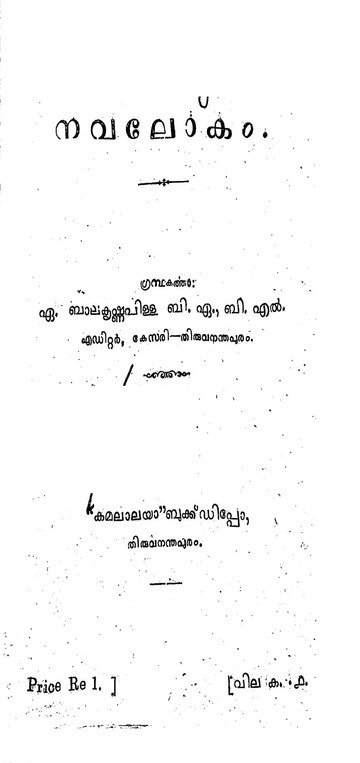

K.C.N: The critic Kesari Balakrishna Pillai (1889–1960) proposed certain aesthetic principles for how future literary works ought to be shaped. In the 1900s, we gained access to modern English education. However, the British included only British literature in the curriculum—no Russian literature, and absolutely no French literature, since the French were their enemies. As a result, Malayalis developed the mental impression that “world literature” meant only British literature. Kesari Balakrishna Pillai was a key figure in changing that mindset. In his book Navalokam, he introduced essential literature and art from Europe—Russian, French, Italian, and so on. Taking those as models, he proposed aesthetic possibilities for how Malayalam modern literature could be shaped. He was one of the pioneering critics who played a decisive role in the formation of Malayalam modern literature.

Mozhi: What is your criterion for a good literary work?

K.C.N: Remember the criteria I mentioned earlier for good literary criticism? Those are also my criteria for good literature.As far as I’m concerned, a good literary work will leave its fingerprint on the reader. In the same way that a good critic leaves his own fingerprint upon the work in a natural response to it. A good literary work reveals certain things—about life, the universe, and relationships—that we did not know before. In response to that, good literary criticism reveals hidden and unconscious aspects of the work. A good work evokes a deep inner stirring in the critic. It is only because of that inner impetus that the critic is able to write about the work. The reason a critical essay is able to stir something within the reader is because of the impetus the critic experienced through the work itself.

Mozhi: To better understand your critical essay on Madhavikutty / Kamala Das—could you give us a historically grounded overview of women’s writing in Malayalam?

K.C.N: K. Saraswathi Amma was the first woman writer to use fiction to express her opposition to patriarchy. But her resistance was expressed directly, not aesthetically. It was like a slap in the face.

It was K. Satchidanandan who first provided a theoretical explanation of pennezhuthu, or women’s writing. In 1984, in his introduction to Sara Joseph’s novel Paapathara (The Ground of Sin), he wrote about women’s writing and its modes. Many critics had offered scattered comments on women’s writing earlier, but it was Satchidanandan who made the first attempt to frame it systematically, in the manner of a discourse.

It was only after that essay that women writers consciously began to ask themselves whether their writing was feminist or not. Thus, the movement of feminist writing emerged. However, this also gave rise to aesthetic complications. Even before beginning to write, the consciousness of whether or not they were a feminist began to shape their writing. There is a major difference between a writer’s unconscious awareness about, say, environmentalism, expressing itself in their work before environmentalism became a mainstream political movement, and a writer consciously identifying themselves as an environmental activist or feminist and creating work from that awareness.

Mozhi: In your reading, which women writers in Malayalam have produced works with strong artistic quality?

K.C.N: According to me, only Madhavikutty. As an individual, she stood out as a feminist, and in her fiction writing, she expressed herself with a natural artistic refinement. Apart from her, to some extent, writers like Geetha Hiranyan and Sugathakumari also had an artistic quality to their writings.

Mozhi: How did male literary critics receive these works?

K.C.N: It was male critics like K.P. Nirmalkumar and Karalkot Vasudevan Nair who pointed out the distinctiveness of Madhavikutty’s fictional world, how she differed from the other women writers.

Mozhi: Madhavikutty expressed herself freely and was also something of a rebel. Wouldn’t there have been a deep inner turmoil inside her?

K.C.N: Yes, if you read her autobiography, you can sense that she carried within her a kind of existential sorrow. Some tried to describe it as a spiritual sorrow, but it was, in truth, an existential sorrow. It’s just a poetic fancy, really, to add mystique to existential sorrow by calling it spiritual. But I believe the two are entirely different. A spiritual person, in fact, has no real problem. The solution to their problem is clear to them. It is only the distance between their self and that solution that causes them sorrow. But for someone with an existential crisis, there is no solution, no redemption. The spiritual path offers a way forward; it has a meaningful goal. In an existential crisis, every path is devoid of meaning. Why all this, is the question one is left with then.

Mozhi: It is interesting that you say there is a difference between a spiritual state of mind and an existential state of mind. Which of the two would you say your own state of mind is closer to?

K.C.N: I have neither faith in spirituality nor admiration for spiritual figures. I also do not believe in God. I have experienced existential crises, yes. But for me, only artistic experiences are essential or meaningful. There is no absurdity in the arts. For instance, I’ve been learning to play the chendai for the past few months. There is no meaninglessness or absurdity in the performing arts, especially in Indian performing arts.

I have experienced existential crises, yes. But for me, only artistic experiences are essential or meaningful.

There is no absurdity in the arts.

Mozhi: That is a very interesting outlook. Art as redemption. Let’s talk a little about the tradition of performing arts in Kerala. Kerala has preserved and continues to perform classical performing arts like Koodiyattam, Chakyar Koothu, Kathakali, and also folk forms like Theyyam and Padayani. Tamil Nadu, on the other hand, hasn’t managed to preserve such a wide range of art forms. How was this possible in Kerala?

K.C.N: About 15 kilometers from here, there is a village called Pulapatta. There you will find the home of Kuthiravattam Thampuran, who owned a lot of land in these parts.. He used to run a kathakali yogam—an organization that coordinated kathakali performers and events. Within a 20-kilometer radius of that area, there are more than ten major temples. Each temple hosts a five-day festival. Kathakali is performed on all five nights. The expenses are borne by the local community. Kathakali yogams coordinate the events. These yogams exist all over Kerala. So Kathakali artists travel from village to village, performing in every festival. Their payment, food, and accommodation are all ensured by the yogam. In addition, landlords and Namboodiris maintained Kathakali kalaris or schools that trained artists. They provided food and shelter for children learning Kathakali, and salaries for the teachers. Thus it was the feudal land-owning class that sustained the performing arts in Kerala.

However, after India’s independence, the EMS Namboodiripad government implemented land reforms—the land ceiling act and tenancy act—to a degree unseen in any other Indian state. It took about 15 years to bring these into effect, and in 1970, they were finally enforced. Most of the land owned by Namboodiris and Nair landlords passed into the hands of their tenants. The tenancy system was abolished. Overnight, the Nairs and Namboodiris became landless. They had known, even ten years earlier, that land reforms were coming, but there was nothing they could do. Nair families who had received English education and taken up employment survived. Among the Namboodiris, very few had acquired modern education. They began selling off even the little land they had left for survival. Land prices were very low. The Ezhavas and Muslims who had once worked for them bought those lands. You can see pictures of these social transformations in Malayalam films of the 1960s and 70s, especially in the works of Adoor Gopalakrishnan and Padmarajan. As the feudal land-owning system disintegrated, there was no one left to support traditional arts, and they began to disappear.

Later, in the 1980s, with the influx of money from Malayalis who had settled in the Gulf countries, these art forms were revived to some extent. Cash flow increased. Kathakali clubs were started in major cities like Ernakulam, Palakkad, Kozhikode, Thiruvananthapuram, and Kottayam, with the financial backing of wealthy Malayalis in the Gulf. They gave Kathakali artists a new lease of life and reintroduced traditional art forms in temple festivals.

From the 1990s onward, Kathakali workshops, appreciation camps, seminars, and even festivals dedicated exclusively to Kathakali began to take place. Today, at least three Kathakali performances take place every single day in various parts of Kerala.

In the earlier feudal system, it was the Namboodiris and landlords who decided the worth of the artists they supported. Chendai music was practiced almost like a hereditary caste profession. But once feudalism ended, new concepts took shape: the idea of the artist as an individual, and of the audience as a critical viewer. The worth of an artist began to be assessed based on their artistic merit.

Mozhi: A question about your essay “The Malayali’s Night.” The essay is built on the observation that Kathakali is composed of circular forms. Did the core idea for that essay arise from your sensory experience of watching Kathakali?

K.C.N: Not from that experience alone. First, the observation about the circle emerged. Later, during a conversation, a friend of mine who worked as an artist in Mathrubhumi said, “The color of Kathakali is black.” That observation stirred my thought in many ways. All the colours in Kathakali are meaningful only in the dark, against blackness. In the light of day, the colours of Kathakali appear pallid, sallow. That was how it began—from blackness came the image of the night, and from night, my mind conceived the idea of the unconscious. How does the unconscious express itself in Kathakali? That became my question. Next, I was taken with the idea of momentariness in kathakali. A sculpture made in stone or a painting drawn on a wall is permanent. It is the ‘sculpture’ and ‘painting’ in Kathakali that represent the archetype of the character. Yet, the sculptural quality in Kathakali’s dance movements, and the painterly quality in its makeup disappear once the performance ends. That made me wonder: was it all a dream?

Then I reflected on how, in Kathakali, negative characters have an elaborate tiranottam sequence that allows us a longer glimpse of their characrer. Positive characters like Rama or Krishna do not. I began thinking about the reason behind that. Later, I felt that Ravana’s ten heads and twenty arms symbolized the manifestation of the whole of the asura clan via his form. In this way, step by step, I conceived the essay and wrote it—through thoughts, observations, and impressions that accumulated in my mind.

Mozhi: Classical Indian performing arts like Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Odissi, and Kuchipudi primarily center around the sānta rasa, or the tranquil mood. Why is there so much violence in Kathakali?

K.C.N: Yes, there is much violence in Kathakali. So much blood, gore. You cannot find this in other art forms. Blood and death are considered contrary to Natyashastra. The howling of negative characters, too. Most Kathakali stories are tales of vadham, slaying—-Balivadham, Duryodhanavadham, Narakasuravadham. Characters like Narakasura’s servant Nakrathundi, who attempted to seduce Indra’s son Jayantha and whose breasts and ears were cut off for that transgression, can be found only in Kathakali. Legend has it that hearing Nakrathundi scream on stage caused a pregnant woman to miscarry. Keechaka’s slow, gasping death is enacted with abhinaya for nearly twenty minutes on stage.

Mozhi: What is the source of this violence?

K.C.N: This violence exists even in the founding myth of Kerala. When Vishnu, in the form of Vamana, asks Mahabali for land measured by three steps and then deceitfully seizes it, how violently he claims the land! To press someone down into the earth with one’s foot—what a great act of violence it is! In a way, the Namboodiris seized the land of Kerala in a similar fashion. Kathakali can be considered a kind of reaction to such violences.

Another point: in Tamil Nadu, there have been so many wars, yet in the classical performing arts there is no violence. But in Kerala’s history, there have been very few invasions or violent upheavals, yet in the performing arts, there is so much violence.

Mozhi: Could the source of Kathakali’s violence lie in folk art forms like Theyyam?

K.C.N: To some extent, yes. The bloodiness within Kathakali, its makeup, and certain ritualistic elements in it are indeed influenced by ritual-based art forms like Theyyam and Thirayattam.

Mozhi: Did the Namboodiris preserve an art form that was, in a sense, against them?

K.C.N: Yes. The Namboodiris did not anticipate that Kathakali would grow to this extent. Moreover, no other Brahmin community in India watches and appreciates an art form with so much violence.

Mozhi: There are classical performance arts like Kudiyattam based on Sanskrit dramas, right? Do they also contain violence?

K.C.N: No. Kudiyattam adheres strictly to the rules of the Natyashastra; there is no depiction of death or blood in it. For example, even Duryodhana’s death is not enacted directly—instead, the messenger who witnessed it simply conveys it with his abhinaya. Kathakali does not follow the rules of the Natyashastra. All it has taken from Kudiyattam are some mudras, hand gestures and a few storytelling techniques—nothing more.

Mozhi: Does Kathakali have a critical tradition?

K.C.N: Yes. In Kerala, there exists a specific tradition of critique—not just for Kathakali, but also for other performing arts like Kudiyattam, Carnatic music, chendai-based percussion art forms like thayambaka, and the tradition of composing poetry in Manipravalam. I would define the nature of that criticism through the Malayalam word “pora,” meaning not enough or lacking. This taste or mode of aesthetic judgment was largely shaped by the mindset of the Namboodiris. Let me explain using Kathakali as an example.

In Kerala, there exists a specific tradition of critique—not just for Kathakali, but also for other performing arts.

I would define the nature of that criticism through the Malayalam word “pora,” meaning not enough or lacking.

By the end of the 19th century, due to British rule, the spread of modern education, and the decline of feudal landlordism, Kathakali was in a state of decline. The poet Vallathol Narayana Menon and Mukundaraja, a member of a royal family, travelled across Kerala, collecting funds from various landlords and established Kerala Kalamandalam, an institution to train Kathakali artists. At that time, Vallathol appointed the renowned Kathakali artist Ravunni Menon as the chief instructor of Kalamandalam. Despite opposition from others, Vallathol insisted that only Ravunni Menon must head the institute.

Vallathol, himself a famous poet—and hailed as a mahakavi—wished to channel his poetic sensibility into Kathakali. He composed a few new verses for certain situations in the myths and asked Ravunni Menon to train students to perform them. Ravunni Menon read the verses and returned them, saying, these don’t suit the form of Kathakali. Vallathol composed a second set, and again Ravunni Menon rejected them, saying, these are not appropriate either. Having appointed Ravunni Menon himself despite severe opposition, Vallathol could not tolerate Menon dismissing his verses. He respected Menon, but Vallathol continued to feel resentment and bitterness toward him—because of Ravunni Menon’s stringent “pora” criticism.

The flip side is that he, Ravunni Menon, too, was a recipient of such criticism. Menon was a great Kathakali instructor. In executing the complex footwork of the adavus, no other artist matched his precision and mastery of rhythm. But his major flaw was that his face did not display any bhava or emotion during abhinaya. In Kathakali, it is essential to show a vast range of emotional states and transitions through the face and eyes. You can watch a Kathakali performance just to see the liveliness in the performer’s eyes. Imagine a face that displays no emotion at all! Among Namboodiris who had a taste for Kathakali, some mocked, “At least if Ravunni Menon had a few smallpox scars on his face, they could be taken as a sign of expression.” When Ravunni Menon heard such a remark, he was deeply hurt. He resolved never to perform again without correcting his facial abhinaya.

His patron, a Namboodiri from the well-known Olappamana house, wrote a letter of recommendation for him to study in Kodungallur. Kodungallur was a significant cultural center in the literary history of Kerala. Kocchu Thampuran of the royal family of Kodungallur was an expert in the aesthetics of South Indian performing arts. Ravunni Menon went there to study. Thampuran reassured him that if bhava did not come naturally to him, it could still be cultivated through specific facial muscle exercises. Thampuran was also someone who desired to bring changes to the abhinaya of Kathakali based on the aesthetics of Bharata’s Natyashastra. When Ravunni Menon came to train with him, he taught him accordingly.

After two years of training in Kodungallur, Ravunni Menon’s facial abhinaya improved significantly. Not only that, he also absorbed the aesthetic reforms proposed by Kocchu Thampuran in his practice. Later, he returned to teach at Kalamandalam. There, he began to pass on the newly refined aesthetic style he had learned in Kodungallur. The form of Kathakali you see today is a stylized version shaped aesthetically by Ravunni Menon under the influence of Kocchu Thampuran. One of the major reasons for this transformation, I believe, was the uncompromising “pora” critique he received for his earlier abhinaya. It was only because the criticism was so deep and cutting that he was able to abandon performing and go seek further training.

Ravunni Menon’s last student was M.N. Paloor, who later became a major poet. Paloor had initially approached Vallathol seeking to learn Kathakali, but Vallathol turned him away, saying that his eyes lacked the expressiveness needed for a Kathakali performer. Paloor then went to Ravunni Menon and shared his disappointment. Ravunni Menon took it as a personal challenge. “Did Mahakavi Vallathol really say that? Then it is my responsibility to turn your eyes into ones fit for Kathakali abhinaya,” he said.

This pora–style critique is, in a sense, a challenge to the person being criticized, a call to action. It becomes the driving force behind their artistic growth and expression. Another characteristic of this pora tradition is that it expresses criticism primarily through understatement. The conversations of Namboodiris are filled with understatement.

Mozhi: Did this critical method influence literature as well?

K.C.N: Yes. In modern Malayalam literature, poet Attoor Ravi Varma’s expressions are characterised by understatement. His critiques are, in a way, forms of “pora”. The refined sensibility characteristic of subtle performance arts like Kathakali entered modern literature, especially modern Malayalam poetry, through Attoor Ravi Varma.

Once, in a conversation with him, I spoke admiringly about one of his older poems, Megharoopan. He immediately responded, “That’s a poem in the old style. I forgot about it long ago. What I seek today are new modes of expression, new visions. If we keep doting on what we’ve written, like a child, that won’t do.” That “pora” persisted within him, always. He always felt unfinished. I believe this kind of unsparing self-assessment and critical sensibility is what kept his artistic vitality alive till the end.

Mozhi: Attoor Ravi Varma learned Tamil. He translated modern poems and Sundara Ramasamy’s novels from Tamil into Malayalam. In a way, was it that very sensibility of “pora” that moved him toward another language?

K.C.N: Yes. It was through formal encounters between Tamil and Malayalam poets at literary gatherings that Attoor Ravi Varma was introduced to Tamil poetry. He realized that modern Tamil poetry was entirely written in understatement. This reinforced his sense of pora about the prevailing aesthetics of Malayalam poetry. He recognized with joy that the modern Tamil poetic tradition was the form most suited to his poetic temperament. They have already written what I wanted to write, was how he felt. He learned Tamil, and translated Tamil poets into Malayalam. The expressive style of his own poetry changed. Instead of Sanskrit-derived words, he began to use Dravidian-rooted words and local Malayalam dialect. For example, he was the first to use the Dravidian-rooted word “peran” (grandson) in Malayalam poetry. Until then, Malayalam had used the Sanskrit-derived “pautran.” Not only his language, but also his inner landscape, shifted. He paid attention not just to the Tamils and the Tamil language but also to the culture of Eelam Tamils. He wrote poetry about the Eelam issue. The life of Attoor Ravi Varma shows us how an old tradition of criticism in Malayalam transformed the outlook of a poet.

Attoor Ravi Varma considered the writer and editor M. Govindan his teacher. I must say a few words about M. Govindan at this juncture. He was well-acquainted with literary figures from all Dravidian languages except Telugu. Not just literature—he had an extraordinary artistic sensitivity that extended to modern drama and classical performing arts. His home in Chennai was always frequented by artists. He ran a Malayalam little magazine called Sameeksha. You may have heard that he had a deep influence on the Tamil writer Sundara Ramaswamy.

The Malayalam writer Anand once went to meet M. Govindan with the manuscript of his first novel. Govindan wasn’t at home, so Anand left the manuscript with Govindan’s wife along with a note saying, “If you have the time, please read this,” and also wrote down his address. It was a thousand-page novel. Govindan read it and wrote back to Anand with suggestions for edits and sections that needed to be condensed. Their correspondence continued—not just about the novel, but expanding into broader discussions. When their letters were eventually compiled into a book, I had the chance to read the manuscript. Each letter could have stood on its own as an essay. One letter contained a discussion on the Shaivite and Vaishnavite traditions in India.

When Attoor Ravi Varma joined Presidency College in Chennai for his postgraduate studies, he became acquainted with M. Govindan. In one of his poems, Attoor writes that it was through his conversations with Govindan that he was able to “emerge from the (mis)path of communism. I found new skies.”

Mozhi: Was M. Govindan also a representative of the “pora” school of criticism?

K.C.N: No, there was a difference between M. Govindan’s approach and Attoor Ravi Varma’s approach. Govindan was someone who pointed out the inner strength, the real potential, of artists who came to him, even if they themselves were not fully aware of it yet. Attoor, on the other hand, highlighted the lack or inadequacy—pora—in those who approached him. Though both are forms of criticism, Attoor Ravi Varma’s negative approach could not help shape new artists. Today, it is hard to point to anyone in Malayalam poetry who began writing because of Attoor Ravi Varma’s influence. He had something to critique in everyone.

By contrast, M. Govindan’s approach helped bring forth many artists—Attoor Ravi Varma himself, Sundara Ramaswamy, and several others. As an editor, I followed M. Govindan’s method. But personalities like Attoor are also necessary in a literary environment.

Mozhi: Do these two critical traditions still have an influence in Malayalam today?

K.C.N: Today, in Malayalam, there is neither a tradition of criticism nor a tradition that fosters imagination. What exists is the “Facebook tradition”—there is no real evaluation of a work or a writer; it’s enough to just hit the “Like” button, or respond with words like “great!” “awesome!” Reactions have been reduced to just that.

Mozhi: A question about the “pora” mode of criticism. For someone to critique with “pora” — that is to say something is not enough, not adequate — they must surely have in mind a complete ideal form of art that satisfies them, right? What is the reference point from which a “pora” critique operates?

K.C.N: The critic does not, in fact, hold in their mind a fully complete, ideal form of art. That is the paradox at the heart of it. The critic cannot point to something and say, “This is perfect art.” That is not possible. No work of art on this earth is ever complete—not in practice, not even philosophically. Which is why in every work of art, the critique of pora is possible. It is by the intensity of its striving for completeness, and the torment and anguish that accompanies the striving, that we distinguish between good art and bad. Only a god can create a flawless work.

The critic does not, in fact, hold in their mind a fully complete, ideal form of art. That is the paradox at the heart of it.

Which is why in every work of art, the critique of pora is possible. It is by the intensity of its striving for completeness, and the torment and anguish that accompanies the striving, that we distinguish between good art and bad.

There is a myth associated with the composition of Bhagavatam. After composing Mahabharata, Vyasa was sitting by the banks of the Ganges in deep sorrow and despondency. The divine wandering sage Narada arrived and asked him the reason for his anguish. Vyasa said that in he had not included Krishna’s divine play, or lila, or his stories about his exploits, nor anything about the gopis in his work. He has only portrayed Krishna as a mere Yadava king, and so his Mahabharata felt like an incomplete work. Narada told him, “If you don’t narrate the stories of Krishna, then anything else you describe has no meaning, no matter how grand. You must write the Mahabharata as Krishna’s story—that alone will redeem you.” Then, the tale goes that Vyasa wrote the Bhagavatam.

Here, the creator Vyasa himself perceives his work as “pora,” or lacking. Narada, the critic, points out how the deficiency in Mahabharata can be filled. Nowhere else in world literature is there the idea that a creator rewrote his own great epic on the advice of a critic. But in Bhagavatam, there are no original characters, no character conflicts. What exists is only the dialogue between god and devotee. There is no desire, no anger, no longing—none of the classical requisites for epic narrative. For eight centuries following Bhagavatam, Indian devotional literature followed this model. So Narada the critic not only enabled Bhagavatam, the foundational text of the Bhakti movement, but also opened the door to an entire mode of composition without conflict, emotion, or human complexity.

In Bhagavatam, there is Krishna’s lila, his play with the cowherd-girl gopis. But the gopis themselves are not characters in the real sense. Kashmiri poets were drawn to the figure of Radha from Rajasthani folklore. There were women in Kashmir who had extramarital relationships with younger men and transgressed social norms of marriage. These women were called asati. Asati-vraja was a narrative form that narrated tales about asatis in song. The Kashmiri poets brought Radha’s story from Rajastani folklore into asati-vraja. Radha, here, is the older woman, Krishna the younger beloved.

This story spread to Bengal. In the royal court of the Pala dynasty, the poet Jayadeva composed ashtapadis, eight-line lyrical verses on the Radha-Krishna love story, in a style that could be sung and performed as dance with graceful gestural movements. These verses later became part of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu’s Krishna-bhakti tradition. Wherever in India the Bhakti movement took strong root, Jayadeva’s ashtapadis were sung.

Those songs reached Kozhikode too. Manadevan, a member of the Zamorin royal family, expanded Jayadeva’s ashtapadis into a performing art form called Krishnattam. In response, in southern Kerala, the king of Kottarakkara created Ramanattam, a performance tradition based on the story of Rama. Ramanattam gained greater fame. Over time, it was stylized, and absorbing certain elements from Kerala’s ritual arts and kalaripayattu, it transformed into Kathakali.