I have ceased to fear death. . .

Two months ago an eminent cardiologist of Bombay, who is a friend of ours, dropped in at my place in the afternoon to take my E.C.G. He told me with great solicitude that I ought to remove myself to the Intensive Cardiac Unit of a nearby hospital as soon as I could, unless I wished to die in a short while, deteriorating in health day by day, until my feet and my face turned swollen, and I became too helpless to move out of my bed.

He held my hand in his and added that he would not have cautioned me so bluntly if I were less intelligent, less brave. Weep if you must, he said, but pack your things before the evening and get your husband to bring you to the hospital. Then he lit a cigarette.

I remained silent. I did not want to tell him that I woke from my bed on some days with a puffiness beneath my eyes and that I had fainted several times during my morning prayers, sitting cross-legged for nearly an hour, reciting my mantras and collapsing suddenly in a heap on the floor.

Whenever my feet swelled up I tucked them beneath the folds of my sari. Whenever I felt a great wringing pain at my side or in my left arm I thrust a Sorbitrate tablet under my tongue and felt its warmth dilating my arteries. I was no stranger to the many signals of warning. But going once again to the hospital was an unpleasant prospect.

I have always regarded the hospital as a planet situated like a sandwich filling between the familiar earth and the strange domain of death. Each time I have been admitted into a hospital-room I have been seized with an acute desire to be left alone. At that moment I am like a honeymooner who desires total privacy for herself and her mate.

Illness has become my mate, bound by ties of blood and nerves and bone, and, I hold with it, long secret conversations.

I tell my heart disease that I have just entered my forties and that my little son still sleeps with his right thumb in his mouth and the left hand tucked inside my nightie, between my breasts.

I tell it that my ancestral home, now under repair, is still unplastered because of the cement shortage and that I would like to live in it for at least a year before my death. I entreat the illness to quieten the ache at my side…

Soon after the admission, the honorary chosen to take care of you, the knight-errant prescribed to fight your battles with the dragon of death, comes to your bedside and undresses you with the help of a nurse, trying to locate the unmanifested symptoms, which in due course will build up for him the ultimate diagnosis. At the touch of his hands your body blushes purple.

Outside your door he talks solemnly with your loved ones. You only hear an incoherent murmur. Besides, by then you would have ceased to care. You have become a mere number. Along with your clothes, which the nurse took off, was removed your personality-traits. Then the pathologist’s henchmen rush at you for specimens of your blood, sputum, urine and bowel- movement.

With all those little jamjars filled and sealed, every vestige of your false dignity is thus removed. In the X-Ray room, an- other nurse unwraps your body while the wardboy who wheeled you in watches furtively from the dark. The display of breasts is the legitimate reward for his labour.

A booming voice orders you to take a deep, deep breath, and lying on the ice-cold X-Ray table you feel secretly amused because you would not have been here at all if taking a deep breath was that easy but you would be walking hand in hand with your little son or seeing a film or picnicking under a fragrant tree.

No, I will not dream of going back to a hospital, I said to the doctor. He gave a friendly shrug. The room was filled with his cigarette-smoke.

It is not that I am afraid of the injections and the drips and all the rest, I said. It is just that I have stopped fearing death…

I have been for years obsessed with the idea of death. I have come to believe that life is a mere dream and that death is the only reality. It is endless, stretching before and beyond our human existence. To side into it will be to pick up a new significance. Life has been, despite all emotional involvements, as ineffectual as writing on moving water. We have been mere participants in someone else’s dream.

I am at peace. I liken God to a tree which has as its parts the leaves, the bark, the fruits and the flowers each unlike the other in appearance and in texture but in each lying dissolved the essence of the tree, the whatness of it. Quiditus. Each component obeys its own destiny. The flowers blossom, scatter pollen and dry up. The fruits ripen and fall. The bark peels. Each of us shall obey that colossal wisdom, the taproot of all wisdom and the source of all consciousness.

I have left colourful youth behind. Perhaps I mixed my pleasures as carelessly as I mixed my drinks and passed out too soon on the couch of life. But does it matter at all? I have turned weary and frigid. My heart resembles a cracked platter that can no more hold anything. But at daybreak lovers still cling at doorways with wet eyes, wet limbs, speaking the words I once spoke.

Perhaps I shall die soon. The jewellery I adorn my body with, in order to look like a bride awaiting her love, shall survive me. The books I have collected, the bronze idols I have worshipped with flowers and all the trinkets stored in my lifetime shall endure, but not I.

Out of my pyre my grieving sons shall pick up little souvenirs of bones and some ash. And yet the world shall go on. Tears shall dry on my sons’ cheeks. Their wives shall bring forth brilliant children. My descendants shall populate the earth. It is enough for me. It is more than enough.

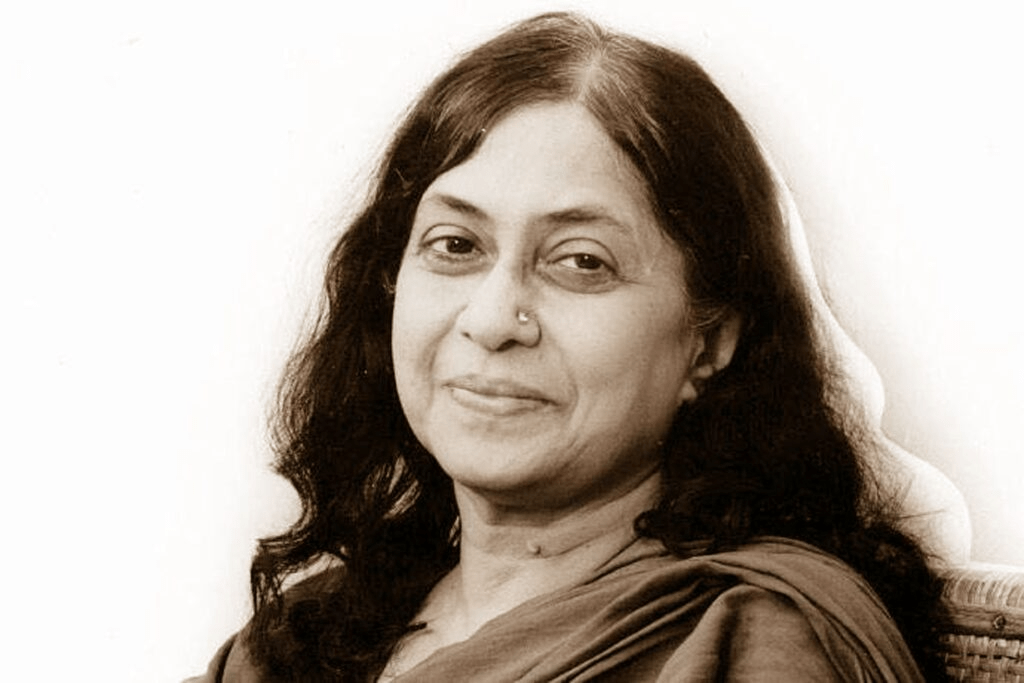

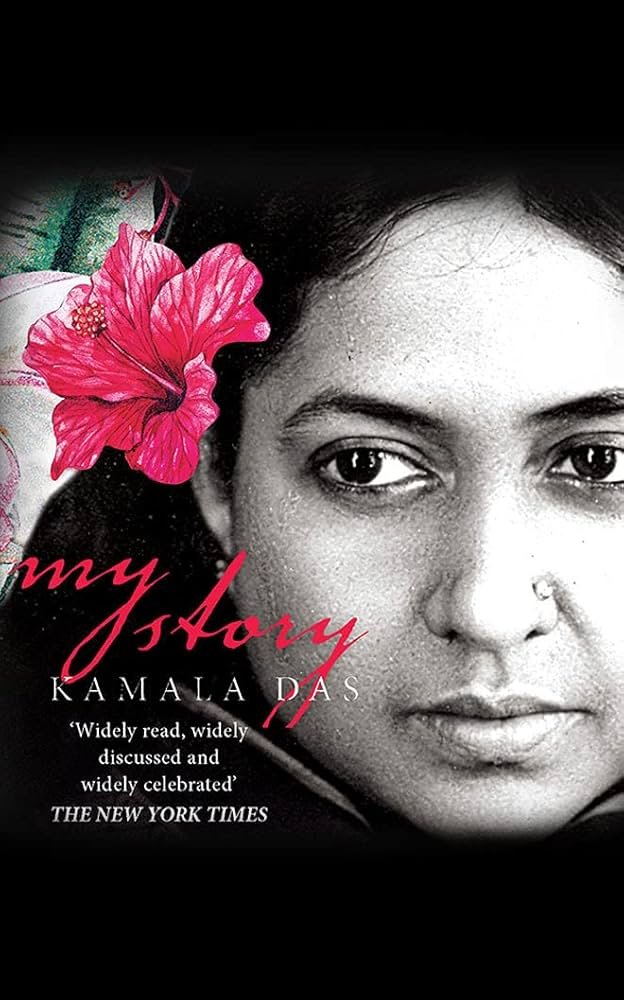

Excerpted from “My Story” by Kamala Das. Copyright of the original is with D.C. Books.

Link to purchase a copy of the book: My Story – Kamala Das