Lord Cornwallis and Queen Elizabeth

A short story by Abdul Rasheed translated from Kannada by Kamalakar Bhat

Placed third in the Mozhi Prize 2024

The modest Rose puts forth a Thorn.

The humble Sheep a threat’ning Horn.

While the Lily white shall in Love delight.

Nor a thorn nor a threat stain her beauty bright.

– William Blake

NATURALLY, the names of the two lovers in this story are not their true ones. These are, in fact, the childhood nicknames we had bestowed upon them during our younger days. Hoovayya, who would later retire as the deputy director of our district’s education department, was known to us as Cornwallis. And as for Queen Elizabeth, that was the title we gave to our Social Science and English teacher, Elizabeth, who taught at the Kannada-medium high school run by the Little Flower Sisters in our village. It was Elizabeth Teacher herself who had once taught us a clever trick for remembering difficult names by associating them with people we already knew. But she had warned us, with a gentle yet firm smile, that these nicknames were to remain a secret within our little group and that, once the exams were over, they were to be forgotten, like the fleeting memories of childhood games.

In eighth grade, we knew her as Elizabeth Sister. When we returned after the summer break to start ninth grade, she had shed her nun’s habit. In eighth grade, we had glimpsed only her fair face and delicate fingers. But in ninth grade, her hair was pulled back tightly, like a nurse’s, and secured with a long hairpin. Her small forehead glistened with sweat, a delicate drop earring graced her ear, and a stray curl of hair cascaded down her neck. We marvelled—was this the same Elizabeth Sister? Even we boys, embarrassed by our half-pants, had switched to full pants, trying to appear grown-up. The girls, too, had matured. And there stood Elizabeth Teacher, no longer a nun, having forsaken her vows, draped in a simple sari that did little to hide her beauty.

We ate our tiffin, packed from home, and perched on a rock in the middle of the river just beyond the school grounds. This rock, where we boys gathered, had been named ‘Paramahansa Rock.’ Nearby stood the ‘Jesus Christ Rock,’ and beside that, ‘Maulana Azad Rock’—names given by our small study group. Across the water lay ‘Mother Theresa Rock’ and ‘Abbakkadevi Rock,’ where the girls sat in quiet clusters. Boys were not to venture there. Yet something stirred in me—a growing urge to join them, not out of fascination with the girls, but because of an inexplicable feeling that, perhaps, deep down, I was more like them than I had realized.

Elizabeth Teacher, our guide, and mentor, encouraged us to discuss our lessons even during mealtimes. She had high hopes for the Paramahansa group, wanting us to secure the top position in the district’s tenth-grade exams. That was why she shared her clever formulas for memorizing names. But instead of focusing on those formulas, our conversations often drifted—to how Elizabeth Teacher had appeared in our dreams. For me, she was like an angel who had descended from the heavens, which is why I began calling her ‘Queen Elizabeth.’ At that age, I found myself filled with strange curiosities about her, drawn in ways I did not fully understand. I even imagined myself wearing drop earrings and a tight blouse.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth Teacher appeared in the dreams of four out of the five boys in our Paramahansa group. But I kept my own dream a secret, unwilling to share it. In my dream, Elizabeth Teacher lay beside Hoovayya, the officer from the Department of Public Education, on a bed of dry leaves in the government cashew plantation. It amuses me to recall it now. In the dream, I lay next to her, like a girl, curled beside Elizabeth Teacher who was close to Hoovayya. When I woke up, I felt a strange sadness. In class, I could hardly look away from Elizabeth Teacher. Every detail of her captivated me, especially the small wound near her elbow—a cut, perhaps from the stones in my dream. Oddly, my own knee hurt, as if I had been injured too.

It was a Saturday, and Elizabeth Teacher was hurrying through the history lesson. ‘Lord Cornwallis took over as Governor of Bengal on the 4th of September, 1786. He established a Sanskrit College in Banaras, started a mint in Calcutta, and established the zamindari system…’ I watched her back as she wrote key points on the board, the chalk tapping rhythmically. Then, the sound of a jeep from outside broke the stillness. Through the window, I saw the headmistress, Sister Mary, welcoming Hoovayya with a garland. The members of the School Development Committee had accompanied him. Taluk Education Officer Hoovayya, newly promoted to District Deputy Director of Education, had arrived for inspection, as he had many times before—first as a subject inspector, then as taluk education officer.

Hoovayya owned a six-acre areca nut plantation, another six acres of paddy fields, and tens of acres of uncultivable land near the village. Whenever he came to the Madikeri ghats to check on his lands, he made it a point to inspect our school, especially Elizabeth Teacher’s class. Each time, he spoke with her at length after sending the children outside. Elizabeth Teacher had renounced her nunhood, trusting his promises, and because of this, she became the target of the congregation that ran the school. She often complained to friends that Hoovayya had yet to take the final step, her frustration spilling into tears. Today, as he entered the school, garlanded, Elizabeth Teacher kept her back to the door, continuing to write on the board, unwilling to turn.

Hoovayya addressed us, his voice heavy with self-importance. ‘Do you know, children, who I am in this district?’ None of us answered, though we harboured a quiet anger towards him. ‘I am the new deputy director of your district’s education department,’ he declared, filling the silence. At that moment, Elizabeth Teacher stopped writing, a flicker of amusement crossing her face. Hoovayya pressed on, ‘Do you know my name?’ he asked, fishing for more.

‘Lord Cornwallis,’ I said aloud.

Silence hung in the air before the girls burst into laughter.

‘Cornwallis? You fool,’ Elizabeth scolded, though I sensed she was secretly amused.

Hoovayya shot her a sharp look. ‘Is this what you teach the children?’ he scoffed, then strode to the next classroom, leaving tension in his wake.

The Saturday afternoon bell rang, and we gathered our school bags, heading toward the river. Sitting on Paramahansa Rock, unwrapping the tiffin, I decided to share my secret dream with the group. I told them what Cornwallis had been doing to Elizabeth Teacher on the dry leaves of the cashew plantation in my dream. But I kept one part to myself—that in the dream, I too was there, in the form of a girl.

About a month earlier, too, Cornwallis Hoovayya had come to inspect the school. He had also visited Elizabeth Teacher’s English class, then. That day, she was teaching us a poem about lilies. ‘Children, the rose is beautiful to look at,’ she explained, ‘but it has thorns beneath. A young goat is cute when small, but as it grows, it develops horns that can hurt us. Now look at the jasmine—white, soft, fragrant. No thorns, no horns. We should strive to be like the jasmine, shouldn’t we?’ As she spoke, her jasmine-like face took on a sharpness.

‘There is no lily in our town, but there is jasmine. You can call a jasmine a “lily,” and then you won’t forget it in the exams,’ Elizabeth Teacher explained to us. As she spoke, Hoovayya arrived in his jeep. At that time, he was still the taluk education officer, and I had not yet started calling him Cornwallis. The Saturday afternoon bell had just rung when he entered the classroom for inspection. Elizabeth Teacher told us to go home. As we filed out, the two of them stayed behind, their voices rising in conversation that stretched long into the afternoon. On many Saturdays, I had seen Hoovayya take Elizabeth Teacher with him to Madikeri. Others in our Paramahansa group had seen it, too, though none of us knew why. But, on that Saturday, as Elizabeth Teacher repeatedly explained the meaning of the lily poem, I began to suspect that something more was at play.

‘You were born with doubts in your stomach,’ says Krishnakumari, who now lives with me in Mysore. She is like me—neither male nor female. Yet, we live as husband and wife. I will narrate our love story later. But for now, let me finish narrating the Saturday encounters between Elizabeth Teacher and Cornwallis.

It was a Saturday evening; one I still remember clearly. The slow drizzle had ceased, but unshed drops loomed in the sky, allowing the evening light to filter through. A rainbow arched gracefully between Nishane Hill on the left and Karadi Hill on the right. I had already pedalled my Atlas cycle along the Madikeri Road as far as Devarakolli. Sensing that dusk was nearing, I began the descent. As the road curved after Devarakolli, right where a hidden lane cut through the government cashew plantation, I spotted Hoovayya’s jeep, parked in the fading light. I leaned my cycle against the jeep and followed the narrow, hidden path. Under a large cashew tree, on the rain-soaked leaves, sat Elizabeth Teacher, her sari slipping off her shoulders. Hoovayya rested his head on the free end of her sari spread beneath them. Elizabeth’s long hair, damp from the rain that had already passed, clung to her face. In the dimming evening light, it seemed as though her sari-less chest touched Hoovayya’s face. I turned quietly, retrieved my cycle, and rode down the slope as the night descended. From that day on, Elizabeth Teacher and Hoovayya began to haunt my dreams. In those dreams, I was there with them, but as a girl lying beside them. Confusion gripped me—I could not tell whether the dreams were a reflection of reality or if what I had seen was merely a dream. Sitting on Paramahansa Rock, eating tiffin with the others, I wrestled with whether to describe it as something I had dreamt or something I had seen. In the end, I chose to say nothing at all.

On another Saturday, I narrated the romance between Elizabeth Teacher and Hoovayya in the cashew plantation, recounting it as part reality and part dream. We were all boys, cycling to school from different villages, and even on Saturdays, we brought our tiffin boxes. After finishing our tiffin, we played underhand cricket on the school grounds with a tennis ball. Once the game ended, we would head to the river for a swim. While the others stripped off their shirts before diving into the water, I always kept mine on. I was too shy to bare myself in front of the boys.

Krishnakumari, my partner in Mysore, has had experiences similar to mine. It seems that everything life has thrown at me, it has thrown at her too. That is why we are together. I play the role of wife, and she that of the husband. Neither of us possesses the organs of a man or a woman, yet we are content, as any couple might be. She is a Leo, fierce as a lion, while I, a Pisces, am slippery like a fish. We live for literature, music, drama, protests… and at night, we make love like animals. We jog around Kukkarahalli Lake three times as if to mock the slow-moving clans of Mysore.

It was on a Saturday that I, in a fit of anger, had christened the new deputy director of the district education department Lord Cornwallis. That day, we boys of the Paramahansa study group had finished our tiffin, played tennis ball cricket, and swam in the river. Dusk was beginning to settle in. While we were still in the water, we saw Elizabeth Teacher sitting slumped in Lord Cornwallis’ jeep as they drove off along the Madikeri Road. After our swim, we got out of the water. The four other boys lined up in front of their chosen plants to urinate, as was their daily ritual. They had each picked a tall parthenium plant—what we called Communist or Congress weeds. Without fail, during school recess, they would relieve themselves on these plants, competing to see whose piss could kill the weeds faster. I never joined in the competition because I had already finished urinating discreetly in the river, without anyone noticing me. I could not stand at a distance like the boys and pee with force; so I lied, saying, ‘My dad is a Communist’ or ‘My mum is in Congress,’ as an excuse to abstain from the ritual.

After they finished urinating on their chosen plants that day, I shared my dream with them. ‘It’s not just a dream,’ I insisted. ‘It’s the truth, and I can prove it.’ They still did not believe me. They mocked me, calling me a poet, a liar, and a eunuch.

‘No, it is true, I swear. I can show you if you want.’

The five of us mounted our bicycles and pedalled up the ascent on Madikeri Road. I still remember it clearly—the moon had risen over the hills, casting a soft glow, and there was a comforting warmth in the air as we rode.

Cornwallis Hoovayya’s jeep stood cold and still near the hidden road in the government cashew plantation. We left all five cycles leaning against the jeep and crept down the narrow path, stopping to hide beneath another cashew tree. There, we saw that the garland the school committee had placed around Hoovayya’s neck now adorned Elizabeth Teacher. She had draped her sari over Hoovayya’s head to shield him from the dew. Looking back, I feel it was a divine moment, one where I should have been lying with them. But instead, like a pack of foxes that had spotted a flock of wild hens, we shouted loudly—so loud that the entire plantation echoed with our cries of ‘Cornwallis and Queen Elizabeth!’ Then, without looking back, we grabbed our bicycles and vanished into the dark.

Within a week of the incident, before the half-yearly exams of the tenth grade, Elizabeth Teacher resigned at the urging of the School Development Board and returned to her hometown in Kolar. Before leaving, she gathered us and said, ‘Children, when you grow up, don’t forget me; remember my nickname “Queen Elizabeth.” That will help you to not forget.’ Her voice wavered, and she even shed a few tears. She was not angry with any of us. In the darkness that had cloaked the government cashew plantation, none of our faces had been visible. She believed, innocently, that the boys of the Paramahansa study group could never be voyeurs. In her heart, she still hoped to awaken something good within those who had shouted ‘Queen Elizabeth’ that night.

Within six months, Lord Cornwallis was demoted by the Department of Education and transferred to Bellary in the name of a disciplinary measure. A year later, he was promoted once more and reassigned to Mysore. By then, I had also arrived in Mysore. Perhaps it was Elizabeth Teacher’s curse. None of us five boys from the Paramahansa Study Group achieved much in life. In my own confusion over my identity as male or female, I left my village for Mysore, where I learned the basics of photography and became a photographer.

You might wonder why I’m recounting these events after so long. In your question lies the beauty and fulfilment of the lives of the two characters of my story.

After all these years—nearly thirty in fact—I saw them both in Mysore last Saturday evening. There was a light drizzle as Krishnakumari and I jogged along the west bank of Kukkarahalli Lake. On our first lap, I saw them approaching us from the front. Lord Cornwallis, who by then had retired and settled in Kuvempu Colony, was easily recognizable. But, I could hardly believe that the person with him was Queen Elizabeth. I stopped, looked back, then ran to catch up with Krishnakumari. ‘You’re dreaming, shut up and jog,’ she chided me.

During our second lap, they were resting by the lake’s embankment, on a bench draped in vines. Elizabeth Teacher had put on weight. Though her face showed signs of ageing, she still resembled a lily flower. Her hair, streaked with white, fell to her chest, and her face retained the same joyful smile. Cornwallis had grown pale, likely due to high blood pressure and diabetes, but looked relaxed in her presence. ‘Don’t shrill like a wild fox, like you did thirty years ago. Just keep quiet and keep jogging,’ Krishnakumari instructed me. So, I passed them without a word. By my third lap, it had grown dark, and neither was there. ‘Probably Queen Elizabeth is fanning Lord Cornwallis with the end of her sari by the banyan tree where the children play,’ I said to Krishnakumari.

She laughed seductively.

*

If someone asks me, ‘Who are you?’ I cannot help but laugh. Similarly, questions such as ‘Are you male or female?’ or ‘Are you Hindu, Muslim, or Christian?’ provoke the same reaction from me. The question, ‘Are you Indian?’ is a bit more complicated. Before I can answer that, some history is necessary.

I was born to a Tamil refugee father, who fled Sinhala by boat, and a Sinhala Buddhist mother. Both escaped from Sinhala, as refugees, on fishermen’s boats and reached Rameshwaram in Tamil Nadu. From there, they moved to a cashew plantation in a village on the border between South Canara and Kodagu, where this story begins. At that time, I was still in my mother’s womb—this was around 1965. India’s Prime Minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri, had just passed away, and Indira Gandhi had assumed power. My parents believed it was Indira Gandhi who had rescued them from certain death in Sinhala and brought them to the cashew plantation. They intended to name their child ‘Indira’ if it was a girl, or ‘Bahadur’ if it was a boy. But I was neither, so they named me ‘Vijaya.’

At school, Mary Sister insisted, ‘No, just Vijaya won’t do. I’ll write Vijayakumar,’ and she listed me in the records as male. When asked about my nationality, my father got flustered and wrote ‘Sri Lankan refugee.’

My mother never let go of her longing for her homeland, always hoping to return to Sinhala one day. When I was in the tenth grade, my father died—run over by a timber truck named Bahubali as he stumbled, drunk, across the street. The name of that truck, owned by a Jain from Puttur, is still etched in my mind. The owners offered some compensation, urging us to settle out of court. With that money, my mother and I moved to Mysore. I found work in a photography studio, gave my mother the rest of the money, and sent her off on a train to Madras. Perhaps she made it back to Sinhala. Being Tamil, I have always been afraid to go there myself, so I stayed behind. The dream of one day seeing Tamil Eelam realized has remained just that—a dream.

‘You are neither a man, nor a Hindu, nor an Indian. You are a pure woman,’ Krishnakumari still whispers, just as fervently, after thirty years of being together. And when she crouches over me, I surrender to her completely.

Krishnakumari hails from Nanjangud, from a salt-selling community. Even into adulthood, her chest remained flat, and from her thighs to her chest, she was covered in hair, like a meadow. She used to strap a pad to her chest, shave herself clean, and work as a dancer in a drama company near Gubbi. Her body, though supple, carried the strength of a demon. She devoured me, like a bug being sucked dry. She is still like that, always seeking to overpower me. I must yield to her—that is all she wants. ‘I’m the hunting dog, and you’re the fleeing deer,’ she says. For the past thirty years, she has been chasing and hunting me down. She is my God.

Now that I have told you this much about our wild chase, my dear readers, I am sure your curiosity is piqued, and perhaps something else too. So, without further delay, let me take you deeper into the story.

The village I spoke of at the start of this tale is an unusual place. Most of its inhabitants are not native to the land. Like my father, they arrived from various places, for different reasons. It is a village that is neither fully a forest nor entirely a settlement. At its heart lies a government-owned cashew plantation, which sprawls from the riverbank at one end and climbs up to Kallal Hill like a head above the village. On the opposite side, the plantation stretches to the foothills of Karadi Hill and runs along the Madikeri Road, fading into Devarakolli. At the crest of Kallal Hill, a waterfall cascades down, roaring perpetually. Below that waterfall stood the guard’s cottage, where my father was housed by the government. The sound of the rushing water was always in our ears, misting the cottage, and in summer, a permanent rainbow stretched across the sky. You might think I was destined to be a poet, but instead of nurturing such dreams, I spent more time worrying about wild elephants.

My father’s homemade liquor, distilled from the cashew fruit, drew entire herds of elephants to our doorstep. He buried some caskets of liquor near the waterfall, saving them for the rainy season, while he carted the rest down to the villages below the hill to sell. After his rounds, he would return home, singing in drunken triumph. Those who could not buy a bottle followed him back up the hill, drank with him, and eventually rolled down the slope, intoxicated, to their villages. After the villagers stumbled away, the forest would come alive with the trumpeting of wild elephants—elephants that had found the hidden caskets of liquor, guzzled them down, and were now drunk and unruly. My father, however, remained unfazed. ‘I am a Tamil tiger,’ he would declare, sitting fearlessly by the fire outside our cottage. And perhaps he was a tiger, for not once did an elephant dare approach our home. But that tiger met his end beneath the wheels of the Bahubali truck. After he was gone, the elephants wandered up to our cottage, searching for the liquor they craved. Finding nothing, they made a terrible ruckus. My mother, a gentle Sinhala Buddhist woman, would clutch me tightly, lying still, eyes shut, as we waited in silence for dawn to save us.

At dawn, from our hilltop cottage, the village below unfurled in shadowed stillness. The black tar road, clinging to the river’s edge, stretched into the darkness. The temple of Lord Shiva stood by the bridge, its cupola just visible in the early light. Beyond the bridge, the minaret of the mosque rose amid the cluster of houses, and further still, the cross of Saint Annamma Church marked the village’s far end. Beside it, the Kannada Medium High School run by the Little Flower Sisters, nestled quietly. Nearby, the school’s playgrounds, areca and coconut groves, pepper vines, and shimmering paddy fields stretched out, damp with dew. On the road, trucks loaded with logs rumbled in from Mysore, and tiny figures moved like shadows against the landscape. In the distance, the bare, deforested hills lay exposed—everyone said another cashew plantation would soon rise there.

With my school bag slung over my shoulder, I descended the hill towards the village. I felt both love and deep resentment for that place, feelings that persist even today. I loved it because everyone was there: Queen Elizabeth Teacher, Mary Teacher, and my friends who gathered on Paramahansa Rock. All those people whose names we had twisted into nicknames as part of our playful attempts to remember history. But I also despised the village, for it harboured men who came to fell the forests and haul away the timber. These men—truck drivers, carpenters, woodcutters, loaders, hotel owners, and workers—sought us, the boys, out as company. They came from everywhere, their eyes always searching, trying to befriend us in ways that made us uneasy. We, the boys of Paramahansa Rock, spoke about it in whispers, partly in fear, partly in jest. By then, we had moved beyond the ninth grade and entered the tenth.

I was disappointed that Elizabeth Teacher no longer taught at the school, and the face of Cornwallis Hoovayya was beginning to blur in my memory. Everyone except I had started to sprout the first signs of beards and moustaches. A Malayali labour manager, who rented a room in one of my friends’ houses, once tried to slip his hand inside my friend’s shorts, only to be bitten in return. When we found out, we were frightened and amused, laughing nervously about it. I, however, was too afraid and embarrassed to talk about my own experiences. Some men had shown an interest in me too. By then, a few of the village boys had become truck cleaners and travelled as far as Mysore. When they returned, they told fantastic stories of big houses, grand palaces, broad roads, and the brothels they had visited—tales that were difficult to believe but impossible to dismiss. I carried these stories with me as I climbed back up the hill to our cottage near the waterfall, always fearing I might encounter a wild elephant on the way.

Mother would be waiting for me by the fire, her face illuminated by the flames, in front of our home where father was no longer present. Even today, when I think of her, that is the image I see—her frightened figure standing before the fire in the evenings, waiting for me to return.

Around the same time, one January afternoon about forty years ago, Krishnakumari arrived in our hometown on a striking red bus from Mysore. It was the day of the annual celebration at our Kannada medium school, run by the Little Flower Sisters, which also marked the school’s silver jubilee. The town elders were preparing to stage a play called Ecchamanayaka. Cornwallis Hoovayya, who had been transferred to Bellary as a disciplinary measure and had since returned to Mysore on promotion, was expected to arrive as the Chief Guest later in the evening. But before his arrival, Krishnakumari was due to reach in the afternoon, travelling by the red bus. She was set to perform a dance in the court scene of Ecchamanayaka. The owners of a Mysore sawmill had graciously arranged for Krishnakumari to enhance the school’s celebration. Each group of students had been assigned specific tasks for the day, and we, the boys of the Paramahansa group, were in charge of hospitality. I, in particular, had been given the duty of looking after Krishnakumari.

I still feel a rush of excitement and goosebumps prickle my skin, whenever I recall that day. The red bus arrived on a crisp January afternoon, the sun shining, though the air remained cold. She was still a little girl, likely two or three years older than me, but dressed head to toe in the elaborate costume of a dancer. The bus stopped on a road lined with people—lay men, drunkards, adulterers, men who preyed on boys, contractors, truckers, loaders, and sawmill workers. When she stepped off the bus, she seemed like a goddess amid the crowd. Her lips were painted red, her cheeks flushed pink, and her eyes framed by thick mascara, while she wore the tight costume of her drama troupe. As she glanced around at our humble village, she seemed confused. Once the bus had driven away, I walked toward her, eager but shy. She initially dismissed me, thinking I was just a small boy, expecting someone older to greet her. I called her ‘Akka,’ elder sister, and she later told me that she found it amusing. She took my hand, and later, I would laugh, saying she was the ‘goddess who had held my hand.’

With her hand in mine, I led her across the street, treating her to a plate of biryani at a local hotel and a cup of Sulaimani tea before escorting her to the school. All along the way, she kept one hand in mine while with the other, she carefully lifted her dancer’s skirt, ensuring it did not brush against the dusty road. She moved with the grace of a ballerina, each step deliberate and light. Before we reached the school, she suddenly needed to relieve herself. I pointed her to the Communist shrubs near Paramahansa Rock. Without hesitation, she turned her back to me, lifted her dancer’s outfit slightly, and, standing like a man, relieved herself right there in front of me. ‘If I’d sat down, duffer, the dress would’ve been ruined,’ she still explains laughingly whenever we recall that day.

I still remember it clearly. Krishnakumari stayed by my side until Cornwallis Hoovayya arrived in his jeep, took the stage, gave his lacklustre speech, and the drama began. In truth, it was I who clung to her, calling her Akka. Hoovayya’s speech was dull, likely because he could not spot Elizabeth Teacher in the crowd, and that only made me hold on to Krishnakumari more tightly. Whenever I think of it, I laugh. Her scent wrapped around me, and I forgot everything—my mother waiting for me in front of a fire to stave off wild elephants, my friends from the Paramahansa group—everything faded away as I watched her perform. Krishnakumari, a girl not much older than I was, danced like a true court dancer in the court scene, her delicate frame moving with grace in front of the backcloth and colourful lights. She performed three or four dances that night, mesmerizing everyone.

Under the moonlight, on a fog-covered road, after the drama had ended and night had fallen, Krishnakumari travelled with Hoovayya in his jeep, heading toward Madikeri. Years later, after seeing Hoovayya and Elizabeth Teacher by Kukkarahalli Lake, I teased her.

‘The man who drove you from my village to Madikeri was none other than Cornwallis,’ I said, laughing. She barely remembered, which was unsurprising for someone who had been with so many men.

‘He sang old Hindi songs as he drove,’ she told me, recalling faint details. Near the Madikeri bus station, he had stopped the jeep, gotten out, put her on a bus bound for Mysore, and even bought her ticket before leaving.

‘A moonlit night in January, with the beautiful Krishnakumari in a dancer’s dress! Didn’t Cornwallis stop the jeep near the government cashew grove, carry you off into the trees, lay you softly on the fallen leaves, and nestle his head between your small breasts for a nap?’ I teased her.

‘Yipes, you shameless! You should stuff your mouth with dirt,’ she scolded, laughing.

When Krishnakumari called me ‘shameless,’ it felt like an invitation, a playful provocation. I desired it too. Seeing them again after so many years by Kukkarahalli Lake had stirred me.

I was ready to be unashamed.

Lord Cornwallis and Queen Elizabeth, by Abdul Rasheed, translated from Kannada by Kamalakar Bhat

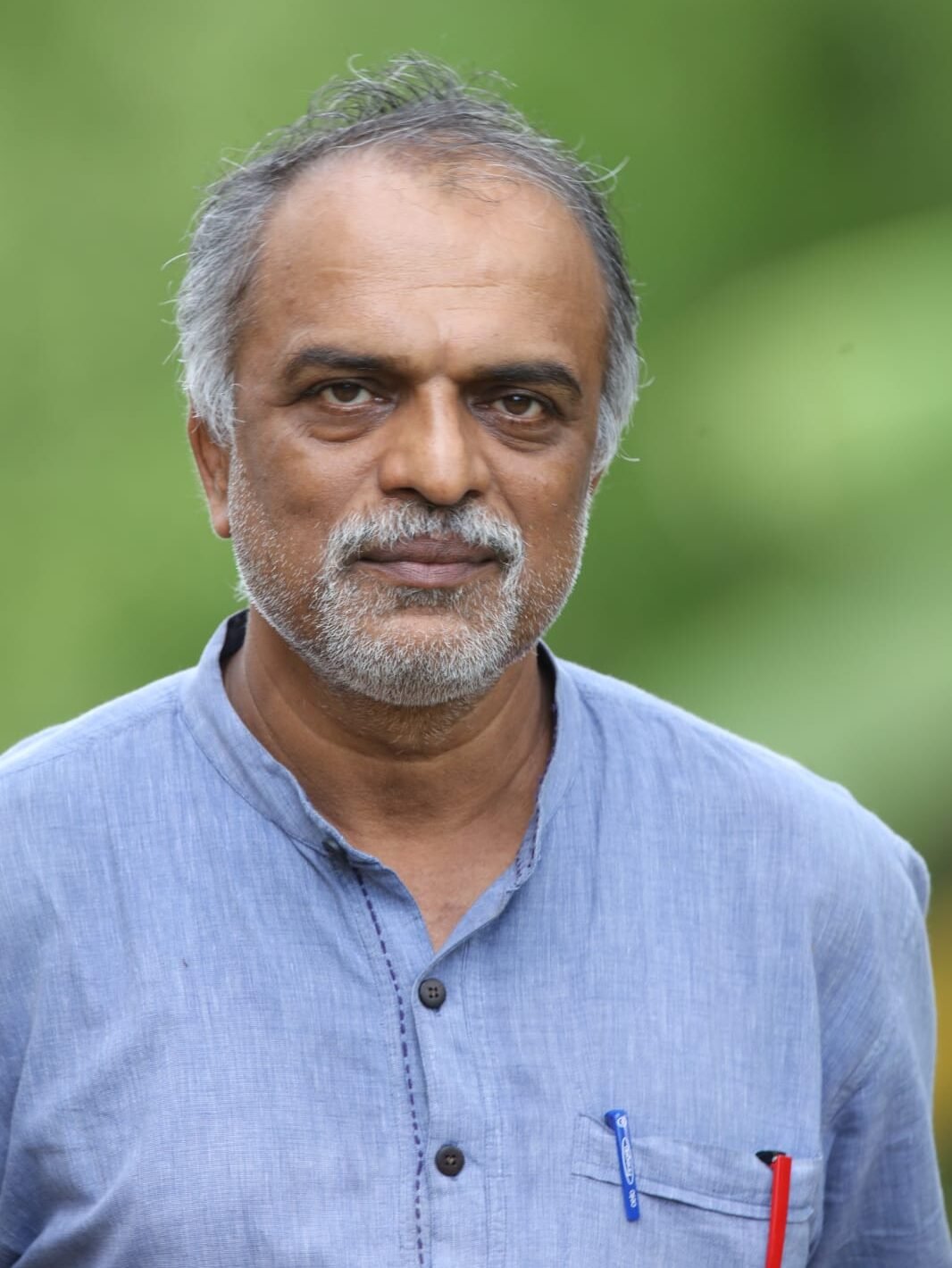

Translator’s note: Abdul Rasheed’s “Lord Cornwallis and Queen Elizabeth” was first published in Kannada in 2012. Narrated from a young adult’s perspective, the story unfolds in the picturesque hilly regions of the Western Ghats, amidst coffee plantations and dense forests. Rasheed masterfully weaves vivid local details into the narrative, creating a rich and immersive backdrop. At its core, the story revolves around a young adult’s discovery of a romantic affair between a teacher and a school inspector. However, Rasheed imbues this seemingly simple tale with deeper layers of meaning. It becomes an exploration of the power of renaming and the fluid, porous nature of gender. Yet, while the narrative invites these complex interpretations, its primary appeal lies in its engaging and lively storytelling.

Rasheed is, above all, a storyteller, weaving a magical and thought-provoking narrative about a young adult’s journey into the complexities of human relationships. The experience of reading “Lord Cornwallis and Queen Elizabeth” is comparable to marveling at something both magical and endearing. Rasheed creates a world brimming with life, where readers, through all their senses, encounter the finer elements of daily existence. His stories defy easy genre categorization, blending elements of story, memory, and reportage. In the telling of his tales, free of any insistent messaging or overt purpose, Rasheed is tender, charming, and adept at captivating his audience. Rasheed’s narrator is mischievous, uninterested in flaunting literary excellence, but eager to offer readers an intense and immersive experience. His storytelling pulsates with vitality, making “Lord Cornwallis and Queen Elizabeth” a deeply engaging and unforgettable journey.

Translating Abdul Rasheed’s prose is like unraveling and reweaving a finely woven carpet, where each thread carries an intricate blend of humour, irony, and poetic rhythm. His subtle yet supple language, especially in portraying young adult characters, teeters between revelation and concealment, enriched by dense details that both propel the narrative and fully immerse the reader.