He would grow up. Grow up and become a big man. His hands would become very strong. He would not have to fear anyone. He would be able to stand up and hold his head high. If someone asked, ‘Who’s that there?’ he would say unhesitatingly in a firm voice, ‘It’s me, Kondunni Nair’s son, Appunni.’

And then, the day would come—he would certainly meet Syedalikutty. He would have his revenge then. Twisting Syedalikutty’s neck between his hands, he would say, ‘It’s you, isn’t it, it’s you who …’

Whenever he thought of it, Appunni’s eyes would fill with tears.

The scene in which he confronted Syedalikutty was one he often imagined when he lay with his eyes closed, or sat by himself in the afternoons in the shade of the kumkumam tree at the gate of the Kundungal family house.

Who was Syedalikutty? Appunni had never seen him. He used to pray that he would not come upon him now, that he would see him very much later, after he grew up and became big and strong. He would go and find him then.

When he started out for the shop that day at dusk, he had neither thought of Syedalikutty nor expected to meet him.

He had come home late from school, having wandered around the temple with his friends, thrown stones at the cashew trees in Sharody’s grove, and brought down the fruits. There was no way they could pluck fruit from Parangodan’s or Achutha Kurup’s cashew groves. They were terrible people. If they caught the children plucking fruit, they would hurl insults at their parents. But Sharody always allowed them to take the fruits if they asked his permission. All the old man wanted were the seeds. It was said that he had a certain affection for children because he had none of his own.

They had gone up the hill afterwards, stamped on wet clumps of ,grass to shape slippery channels to play in and lost track of time.

On the days when he came home directly from school, Amma would not have come back from the illam, the Namboodiri household where she worked. He would swallow the kanji in the covered bowl hanging in the rope uri in the kitchen in one long gulp. By the time he went to old Muthaachi’s but and sat down to exchange a bit of gossip with her, Amma would be back.

When he got back that day, Amma was throwing paddy husk into the fireplace over which dinner was cooking, to get the fire going.

‘Why’re you so late?’

‘Nothing, Amme.’

‘How many times I’ve told you, Appunni, that you’ve got to be home by dusk.’

He said nothing in reply. He knew that was as much as Amma would say in rebuke.

He drank his kanji standing. Then Amma said,

‘Go down to Yusuf’s shop, son, and get me coconut oil for two annas.’

He looked out. The sun had set completely. Darkness had not quite fallen, but the sky was black. Once it was dark, he was afraid to go down the lane where screwpine bushes grew thick on both sides. Eroman the sorcerer had been cremated by that lane. Appunni was reluctant to go that way.

‘We’ll get some tomorrow, Amme.’

‘There’s not even a drop to touch to my hair. Just make a quick dash.’

He hesitated. If he said he was afraid, Amma would tell him not to go. But that was shameful, wasn’t it? He was not such a small child, after all. He was in the eighth now. It was him that Master had made the monitor of the class.

‘Get going, Appunni. If you bring it back quickly, I’ll give you rice mixed with fried onions.’

He did not hesitate any longer.

‘Give me money and the bottle.’

Rice with fried onions was no small treat. He had tasted it only twice or thrice. Oil was poured into a frying pan over finely chopped onions; as the onions started to brown, Amma would toss rice in with a ladle. Ah, the fragrance that rose from it when it was served on a plate and set before him!

Hai, just to think of it brought a potful of water to his mouth.

He thrust the coins into the pocket of his red shorts, picked up the bottle, and ran out.

When he came to the lane that ran through the thicket of screwpine, he hesitated for a moment. No, it wasn’t all that dark yet. But there were dense screwpine bushes on both sides. He had heard that hooded cobras lived in the pits between the bushes. They liked the scent of screwpine flowers. Sweet scents, good music, and beautiful women: these were what cobras liked. Were these good things meant only for cobras?

He knew every step, stone, and pothole in the lane. Surely there was danger only if he walked slowly? He broke into a quick run. He did not stop until he reached the edge of the paddy field beyond the lane.

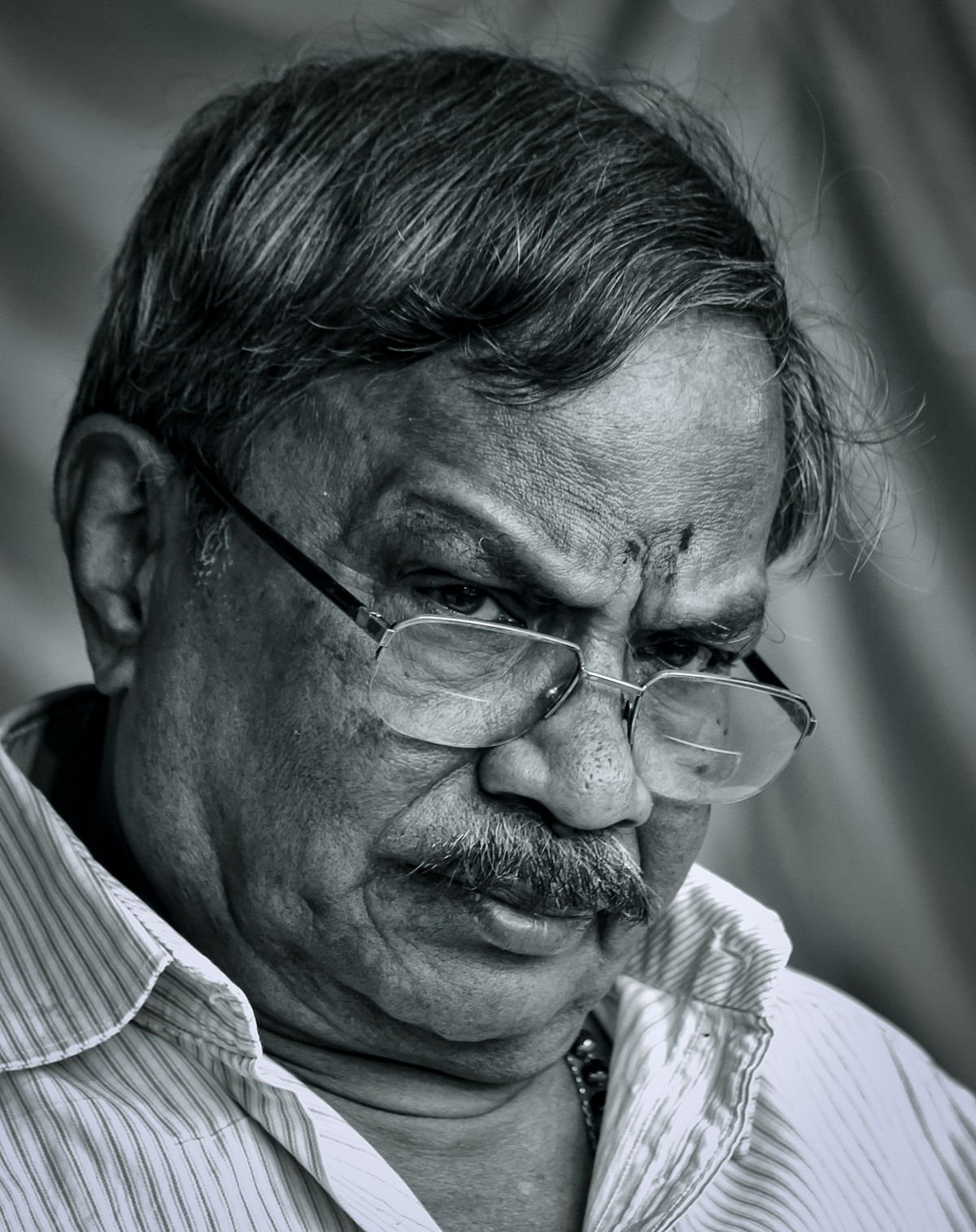

He had to cross one more field to get to the bazaar. It was right on the bank of the river. All the shops had thatched roofs, except one which had a tiled roof. No business was conducted in it. Someone lived on the first floor.

Lamps had been lit in the shops. Most were flickering hurricane lamps. OnlyYusuf’s shop had a petromax lamp. It was the biggest shop in the village, the only one which displayed firecrackers for sale when Vishu, the Malayalam New Year, drew near. A tailor had come from Pattambi recently: Kudallur’s first tailor. He kept his sewing machine inYusuf’s shop and did his tailoring there.

Appunni liked going to Yusuf’s shop. He could watch the tailor at work as well.The sight of the needle going rapidly up and down making a lada-kada’ noise while curls of coloured cloth billowed out was well worth seeing.

He had been thinking for many days now that he must tell Amma not to buy him shirts from Ravuthar. All his three shirts had been bought when Ravuthar came around hawking his wares. Two were too loose and one, too tight. They could buy cloth and give it to the tailor. His measurements would then be taken while everyone in the shop looked on. If the measurements were taken with a tape, the fit was sure to be correct. He would be able to watch the shirts being cut and sewn with a certain authoritative air.

Yusuf’s shop was crowded when Appunni entered. It was the time of day when the cherumis returning from work with their daily wages were buying provisions.

‘Kerosene for two quarter annas.’

‘A nazhi of salt’.

‘Betel leaves and tobacco for a quarter anna.’

‘Hurry up, Musaliyar, I have to go.’

All Yusuf did was sit in front of the box. It was Musaliyar, with the long white beard that came down to his neck like a billy goat’s who handed out things. There was quite a crowd. The cherumis talked to one another about happenings at home or exchanged news about the houses they worked in while they hurried through their purchases. A young cherumi scolded Musaliyar for letting a drop from the half-anna’s worth of coconut oil that he poured on her head fall on the ground.

The tailor had moved his machine into the shop and left.

Appunni stood quietly on the veranda. Oh God, he thought, it’s getting late.

It was.at dusk that poisonous snakes crept into the screwpine bushes. Eroman the sorcerer had been cremated on the roadside.

‘Coconut oil for two annas.’ In the commotion made by the cherumis, Musaliyar did not hear him.

Appunni made an attempt to push his way through them. It wouldn’t matter if he touched the cherumi women and was polluted. He would have a bath anyway as soon as he got home. But when he drew closer to their dark bodies, the odour of mingled sweat and oil and dirt nauseated him. He drew back and stood for a while watching the moths flitting around the petromax lamp.

It was then that two people entered. A short, stout man in a white shirt with a small moustache flecked with grey. The other was Padmanabhan Nair who had run a teashop by the ferry for a long time and then gone out of business. Appunni knew him, two of his children were in his class.

Appunni moved closer to the wall and leaned against the shutters stacked there.

‘So business is excellent, Moyalali!’ called out the short, stout, white-shirted man. The cherumis turned when they heard his voice. Yusuf, who was seated near the table counting out change did not see him.

‘Who is it?’

Musaliyar, busy packing coriander seeds in a teak leaf, smiled, baring teeth stained red with betel juice and said,

‘My God, who is this? You’re not dead yet?’

‘I’m ready. Maybe Israyel doesn’t want me, Moyaliyar.’

Yusuf got up. When he caught sight of the white-shirted man he too said, ‘My God, who’s this now?’

Musaliyar asked, ‘When did you come?’

‘By the five-thirty train.’

Musaliyar said as he tied up a packet, ‘The rascal’s put on some weight, hasn’t he, Pappanavan Nair?’

Padmanabhan Nair, who was watching the cherumi women while he sat on the stone platform smoking a beedi, said, ‘It’s all that food in strange places.’

Musaliyar caught sight of Appunni as he turned to spit into the courtyard.

‘What do you want?’

For no reason, Appunni suddenly felt sad. He was afraid he would cry in a while. He said without looking at Musaliyar’s face, ‘I came to buy coconut oil.’

The cherumis muttered something to one another.

‘Who is this child?’ the white-shirted man asked Padmanabhan Nair.

‘Our Kondunni Nair’s son. Vadakkeppattu…’

Appunni did not raise his head.

The cherumis suddenly fell silent. Two of them who stood near Appunni whispered something to each other. Those in front moved aside a little. Appunni could go up in front now without elbowing anyone. Musaliyar took the bottle from him, placed a funnel in it, dipped a small ladle in the tin, and poured out two ladlefuls, then an extra drop as well.

Appunni paid and twisted a dry leaf into the bottle to close it. As he was about to go out, the white-shirted man asked,‘You’re going alone?’

Appunni did not realize at first that the man was speaking to him.

‘It’s dark outside, child.’

Appunni muttered something that no one could hear. Kochi, the old cherumi who worked at the adhikari’s place, called out: ‘Wait, Cheriambra, don’t go alone. I’m going that way.’

Kochi tucked the screwpine leaf bag that held her money and betel leaves and all the things she had bought into her ample waist and followed him out. She lit her palm-leaf torch at the oil lamp in the shop next door and said, ‘Go on, Cheriambra.’

Appunni was no longer afraid. He thought there was a faint fragrance of screwpine flowers in the lane, but at least there was light where he walked.

He asked, ‘Who was that, Kochi?’

‘Who, Cheriambra?’

‘That man in Yusuf’s shop.’

‘Don’t you know? That was Syedalikutty Mapilla.’

‘Which Syedalikutty?’

‘Of Mundathayam. He’s been away for years now.’

Syedalikutty! Goosebumps burst all over him. The thick, short, rough hands, the hairy body, the round, bloodshot eyes—so that was Syedalikutty. The man who …

He suddenly remembered waking at dawn to a scene in Kathakali in the temple courtyard: Bhiman, seated on Dussasanan’s chest, tearing open his stomach and pulling out the entrails. He, Appunni, would sit like that on Syedalikutty’s chest and …

But he wasn’t strong enough yet, or old enough.

Appunni gasped for breath.

If he were to give Syedalikutty a push while he walked by the edge of the quarry or in the nartow lane under Anappara … or throw a stone at his head …

‘You go along now, Cheriambra.’

He realized he had reached home.

‘Appunni!’ He heard Amma’s voice. She was waiting anxiously at the gate.

He ran up to her, gasping.

‘Oh my forefathers! My insides were on fire!’

Appunni did not say anything. He thought of the quarry, of blood streaming from a crushed head …

‘Why did you take so long, Appunni?’

‘There was such a crowd there.’

He wrapped a worn, shabby towel around his waist and went to the well to bathe. Amma drew water and poured it over his head. Even now, it was she who scrubbed him and gave him a bath. He dried his hair himself, but Amma would look at it, say it was still wet and dry it again, rubbing his scalp hard.

Somehow, the rice fried with onions did not seem to have its usual flavour.

Amma closed the front and kitchen doors, washed the vessels, inverted them on the floor, then spread his mattress irk the only room they had and her own mat next to it.

When the lamp was extinguished and it was dark, he felt afraid, he was not sure why. In the dark, he kept seeing a head of stubbly hair and bloodshot eyes.

‘Are you asleep, Amma?’

‘No. Why?’

Should he tell her? ‘Um … um …’ He closed his eyes tight and prayed he would fall asleep quickly.

‘Amme!’

Amma put out her arms, drew him close and asked, ‘What is it?’

He hesitated again. Should he tell her?

‘I—I saw Syedalikutty.’

Amma didn’t ask which Syedalikutty. She drew him even closer to her, pressed her face against his back and said, ‘Go to sleep, my little one.’

It was not Amma who had told him the story. He had gleaned most of it, a little at a time, from Muthaachi. Her hut was in their compound, on the southern side. He spent his time there when he had nothing else to do.

Muthaachi did not stay in her hut all the time though. She sometimes wrapped herself up in her yellow woollen shawl (which he heard had been brought from Colombo) and went off, leaning on her stick. She would come back only after three or four days. There were houses she visited regularly—Thendeth Illam, Mankoth Illam, and a couple of Nair tharavad houses. She had to be given rice and coconuts in these places without asking for them. Muthaachi would often say, to console herself, ‘I don’t go around begging, you know.’

There was no one in Kudallur who did not know Muthaachi. She had had three husbands when she was young but had never borne children. The first husband had abandoned her. And she had abandoned the second and third. Seventy-year-old Muthaachi could still take part enthusiastically in Onam and kaikottikkali dances with little children. If she visited wealthy houses, she usually stayed a day or two. The women were expected to give her rice when she left and the young men coins. She would then go around praising the generosity and status of all those who gave her money and rice.

When she was young, Muthaachi used to nurse the women in all the houses where there was a childbirth or an illness. She had brought most of the people in the village into the world. And ushered many to their death. But she did not like anyone saying that Kalan, the God of Death, would come for her one day.

‘So you’re in a hurry, are you, children, to take Muthaachi to the southern yard to be cremated?’ she would ask and then console herself: ‘My turn won’t come as quickly as all that.’

Whenever she came back from a journey, she would stay in her hut for a few days. That was the time Appunni was the happiest. He would go and sit down on her rope cot. All the good things she had collected, juicy mangoes or jackfruit pappadams from Thendeth Illam, were for him. What Muthaachi needed was an audience and even a two-year-old child would have done. She had so much to tell.

It was from Muthaachi that he had learnt many things about his father.

‘When Kondunni died, Appu, you were just this high.’ Muthaachi called every boy Appu. And every girl Ammu.

When his father died, Appunni had been only half the size of Muthaachi’s index finger! Appunni was very amused.

It had not been a natural death. Someone had given him poison to drink .

‘There’s never been a boy as affectionate as he was in this whole region. So big-built, an elephant could not have wound its trunk around him. Whenever he saw me, he’d give me money to buy betel leaves.’ Muthaachi would stop, stroke Appunni’s head and say,

‘God didn’t will happiness for your mother.’

Appunni had only a vague memory of his father. Everyone Appunni met talked about him. The villagers had loved him. They had needed Kondunni Nair for everything. He had been in demand for every sort of occasion: a wedding, a sixteenth day funeral rite, the construction of a house.

But his own family had hated Achan, Appunni’s father, from the time he was a young man.

‘Good-for-nothing fellow, let him go around throwing dice!’ Appunni had heard that that was what his father’s mother used to say. Achan had been an only son and when his mother died, he had been left alone in the world.

Kondunni Nair had had an excellent reputation as a pagida player.

They still played pagida on the platform under the banyan tree for the Onam, Vishu, and Thiruvathira festivals. There was a competition between the Kudallur and Perumbalam regions. But all the expert dice throwers had died and there were only a few young players left now. The older people complained: ‘No one has a passion for the game anymore.’

Whenever he heard the sound of the dice spinning and ululations echoed through the air, Appunni would think of his father and a sense of pride would outweigh his pain.

There had been only one player in the village who could make the dice fall showing the exact numbers he had predicted—and that was his father.

‘Listen, all of you, I saw with my own eyes. It was during the last round with the Perumbalam folks. Marar was playing for their side. They were on the point of winning, the dice had to be thrown only one more time. If we were defeated, we’d lose our honour. None of our players had lasted, they had given up one after another. Imagine, the other side had got washerman Choppan to perform sorcery! We learned about it only later. We needed a total of thirty-two points to win. Achumman stood with the dice in his hand, staring at the sky.

‘Oh God, it’s all over. The truth was, Achumman didn’t dare play. If they didn’t win this round, they’d lose the game. He looked at me and said softly, “What now, Kutta? It’s the honour of the village that’s at stake.” But Achumman wouldn’t give up that easily. He turned and asked loudly, “Any of you boys want to try?”’

‘Give me the dice, Uncle.’ Kondunni Nair!

Marar and his companions invoked all the gods of the earth, screaming to them to make their opponents lose. The ululations could be heard miles away.

‘Why should I worship that slut of a goddess?’ Infuriated, Kondunni Nair beat his breast. ‘Against whom?The Bhagavathi! My hair stands on end as I say it.’ He closed his eyes, said a prayer and threw the dice. A crystal clear twelve!

‘His eyes were bloodshot. He was a sight to make you tremble.

‘He threw the dice a second time. Twelve again!

‘And again. Twice three. Six.

‘There you are,’ he said and spinning the dice once more, he walked off. The dice stopped rolling only when he reached the gate. Pagida: another clear twelve! Thirty-six in all!

‘There’ll never be a man like him again,’ said Kudallur’s leading current champion, Kuttan Nair. They said Kondunni Nair had gone to Kuttippuram and Valancheri to play when he was just twenty-one and defeated the experts there.

There was a washerman from the south who had never been defeated in a game. He would play only in front of his ancestors’ shrine. Everyone who had challenged him had lost. One Avittam day, the day after Onam, Achan set out to play with him. Appu Panikker went along with him. Even now, there was not a day when Appu Panikker didn’t talk about it. They began to play early morning one day and it was on the third day that Achan won a round. The washerman tried every trick he kneW. The dice stopped spinning only on the evening of the fourth day. The crowd watching the game was so dense that if you threw a speck of sand, it would not have reached the ground. When Achan got up, victorious, the washerman joined his palms and said, ‘Adiyan will never play with you again.’

He gifted Achan a pair of bell-metal dice weighing four pounds. The young men of today would never be able to hold or spin them. It was with these dice that Achan defeated the Panikkers of Kanoth.

There were so many stories like this about his father.

Most of the young people in the village used to be Achan’s admiring followers. He was popular with everyone. It was only after his marriage that many of them abandoned him. Because, they said, he had insulted Amma’s tharavad. Many people detested Achan for having insulted the Vadakkeppat tharavad.

Achan’s tharavad was not a greatly respected one, the reason being that three or four generations ago, one of the women had gone astray. To make things worse, Achan kept company with people of all castes. He drank tea in teashops run by mapillas. Drinking tea was considered wrong in itself in those days. And Hindus certainly did not drink tea made by mapillas, that was an even bigger wrong. As forplaying pagida, the Vadakkeppat people saw it as a crime. To make things worse, Achan always drank toddy before he played. A girl from the Vadakkeppat tharavad could certainly not be married to such a man.

Amma had a brother who had died. If he had lived, Appunni would have called him Madhava Ammaaman—Madhava Uncle. He and Achan had been great friends.

It happened on a day when Valia Ammaaman, the seniormost uncle and Madhava Ammaaman’s elder brother, was not at home. No one used the pathayappura in those days. At dusk, Madhava Ammaaman and Achan were seated upstairs in the pathayappura, talking. They did not realize how late it was. They were startled to hear Valia Ammaaman’s voice in the front veranda.

‘Who’s that, Madhava?’

It was Achan who answered. ‘Kondunni of Thazhathethu.’

‘What business do men who do not belong to this tharavad have here after dark?’

Achan said respectfully, ‘I was not in the northern wing, in the women’s quarters. I came here to talk to one of the men in the family.’

Valia Ammaaman paced up and down furiously. ‘You should have sat in the front veranda, finished your business, and left. The men of Thazhathethu have not risen so high that they can enter the Vadakkeppat pathayappura.’

Achan controlled himself. ‘I did not come here in secret. If Kondunni wants a girl from here, he knows how to get her.’

Valia Ammaaman lunged forward and made a sign ordering him out, ‘Phoo!’

Achan cleared his throat, spat and exclaimed, ‘A fine tharavad, indeed!

It was Muthaachi who had described all this to Appunni.

Someone had been standing behind the wooden bars above the ledge in the thekkini watching the scene—Amma.

Amma had been of marriageable age then. She was the younger niece of the Vadakkeppat family’s seniormost male member, the karanavar. The family had decided to celebrate her wedding on a grand scale. The sambandam partner chosen for her lived twelve miles away and belonged to a prestigious tharavad, owning vast lands and fields. The wedding pandal that was put up covered the entire courtyard. The members of every Nair house from Poomanthodu to Kaithakkadu had been invited. Brahmin cooks had been brought from Kodikunnathu to prepare the feast.

But the wedding did not take place.

It was only when the bridegroom’s people arrived at the gate that the women of the house discovered that the bride was missing.

‘What happened, Muthaachi?’ asked Appunni, his heart throbbing wildly.

‘Kondunni stole Parukutty and took her away, that’s what happened.’

Appunni had heard the story of how Ravanan had seized Sita and taken her away in his aircraft, the pushpaka vimanam. Ravanan was an evil man, it was wicked to have stolen Sri Raman’s wife.

Then he thought of how Arjunan had stolen Subhadra. Arjunan was a great warrior. There was no archer who could defeat him. The story was in his Malayalam textbook. Arjunan had gone to Sri Krishnan’s household in the guise of a sanyasi and made off with Subhadra. Clever fellow! The Yadavas who tried to attack him could not even touch him!

Whenever they came to the part in the story where Subhadra was lifted into the chariot, Appunni would remember the way hunchback Chathu Nair described his father carrying his mother away.

Only Chathu Nair had the right to describe it. ‘I saw it happen, folks. A man like that will never be born again,’ he’d say.

‘It was the monsoon season and even the water in the fields had risen chest-high. Leeches lay thick on the ground. When he came to the water, he lifted her up in his arms as if she were a sliver ofbroomstick and walked right across.’ Hunchback Chathu Nair had been just behind, carrying a hurricane lamp. ‘What, if they follow you?’ he asked.

He turned and looked at Chathu Nair. ‘I’m a man, Chathu. Once a man is born, he can die only once.’

When Muthaachi told him these stories, Appunni would often think of Thacholi Chandu and Komappan. Of legends he had heard as a child of how they had fought and won battles…

‘But God did not will her to be happy.’ Muthaachi would say at the end.

An excerpt from “Naalukettu: The House Around The Couryard,” by M.T. Vasudevan Nair, translated by Gita Krishnankutty

Republished with permission from Oxford University Press.

To purchase a copy of the book: Naalukettu – M.T. Vasudevan Nair (English)

Related links: